The impact of study abroad on Japanese language learners’ social networks

Published December, 2011

Pages 25-63

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21159/nv.05.02

New Voices

Volume 5

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2011

Permalinks for references are only available in the HTML version of this article.

Abstract

Study abroad is commonly believed to be an ideal environment for second language acquisition to take place, due to the increased opportunities for interaction with native speakers that it is considered to offer. However, several studies have challenged these beliefs, finding that study abroad students were disappointed with the degree of out-of-class interaction they had with native speakers. It is therefore important to gain an understanding of the study abroad context and the factors that promote and constrain opportunities for second language (L2) interaction.

This paper examines the complexities behind six Japanese language learners’ interaction and social relationships with native speakers through analysis of their social networks before, during, and after a study abroad period in Japan. It also compares the networks that were formed in an urban and a regional setting in Australia. The paper concludes with a discussion of the benefits of study abroad and offers several implications for foreign language teaching and study abroad program development.

Introduction

It is commonly believed that one of the best ways to learn a foreign or second language is to develop friendships with native speakers and to communicate with them using that language.1 There is also a widespread belief that students studying abroad will be immersed in the target language and culture, providing ample opportunities to meet and interact with native speakers.2 Study abroad is therefore considered an ideal environment for second language acquisition (SLA) to take place. However, several studies now exist that have challenged these common beliefs, and thus there is a need for further research into the study abroad context, and how it impacts learners’ interaction with native speakers once they return to their home country.

A possible means of examining the complexities behind students’ interaction and social relationships with native speakers is through analysis of their social networks, which Milroy defines as the informal social relationships contracted by an individual’.3 An increasing number of studies investigating social network development in study abroad contexts now exist.4 Kurata has also examined changes in learners’ social networks that occurred after various sojourns in Japan.5 However, her participants were not limited to study abroad students, and, consequently, the nature of the study abroad experience and its impact was not explored.

The current study thus focuses on the following research questions:

- What are the characteristics of Japanese language learners’ networks before, during, and after study abroad?

- What factors influence network development with native speakers whilst on study abroad?

- How does the study abroad experience impact Japanese language learners’ social networks and interaction with native speakers once they return to their home country?

Literature Review

Although a comprehensive review is beyond the scope of this paper, the following sections briefly introduce relevant findings firstly pertaining to study abroad, and then regarding language learners’ social networks.

One area of particular interest in the study abroad literature is the role that learner interaction with native speakers has in cultivating language proficiency.6 Whilst Lapkin et al.,7 Regan,8 Isabelli-Garcia9 and Hernandez110 have found that interaction with native speakers contributed to language gain, Freed,11 Segalowitz & Freed,12 and Magnan & Back13 found that although a study abroad period could lead to gains in oral proficiency, it was not correlated with interaction with native speakers. However, these researchers have suggested that the duration of one semester or less was probably not long enough for their participants to significantly invest in the kind of social relationships that provide the interaction necessary to enhance SLA.

The issue of study abroad students grouping together with other students who share the same native language, and using their L1 to communicate, is also frequent in the study abroad literature.14 Several of these studies have found that this impedes development of friendship with host nationals and also subsequent SLA.15 Ayano discovered that for Japanese students studying abroad in Britain, it was difficult to establish closer relationships with British students whilst maintaining those with other Japanese students. She suggested two main reasons behind the problem: the lack of opportunity for developing relationships with native speakers, and too much density within the Japanese network.16

Several studies have also found that student dormitories, where study abroad students are often housed, are unsupportive of L2 use.17 This environment usually offers students ample contact with other L1 speakers, which means that in the most extreme instance, students only use the target language during class and in limited circumstances outside of it.18 Although many study abroad organisers also try to facilitate learners’ native speaker interaction and socialisation into the target community through homestays, student disappointment in homestay experiences that did not offer extensive opportunities for linguistic and social interaction is frequent.19

Conversely, participants in several other studies claim that the homestay experience greatly contributed to their improvement in speaking skills in the target language.20 Tanaka suggests that although the study abroad context offers greater opportunities for L2 interaction outside the classroom compared to at-home settings, it is up to the students whether they utilise the opportunities’.21

A number of studies regarding Japanese learners’ networks in Japan offer some interesting findings. It has been found that participation in a variety of activities will assist development of close and mutual relationships with native speakers.22 Morofushi found that by participating in club activities, tutoring, and buddy systems offered by universities, exchange students in Japan generated mutual engagement with native speakers.23 Kato and Tanibe also found that participation in university clubs was a key facilitator for network development, along with activities outside of university, such as homestays and short courses.24

Networks with compatriots, on the other hand, have been found to impede the establishment of networks with native speakers and subsequent improvement of Japanese language.25 Pearson-Evans also found that whilst conational friends in Japan provided solidarity and support, this network reduced motivation to adjust to the host culture and was a stumbling block’ for the pursuit of Japanese friends. However, when students did develop relationships with the Japanese, they acquired a deeper understanding of Japanese language and culture.26

Finally, Kurata has investigated the influence that a sojourn in Japan has on the various characteristics of Japanese language learners’ networks in an Australian university setting.27 She found that students’ social networks after a sojourn were larger in size, included a wider variety of members with a multiplexity of relations and activity types. It was also found that students used Japanese more frequently within their social network after their sojourn and formed more equal relationships with their interactants. Furthermore, students in this study maintained contact with their networks in Japan, which provided valuable sources for friendship, Japanese language input and output, and also proved beneficial in dealing with difficulties in written Japanese.28

Although Kurata argues that an in-country experience therefore has a positive influence on learners’ development and maintenance of social networks in both the abroad and home contexts, she does not address reasons behind these changes in depth. Thus, a deeper examination of learners’ experiences whilst abroad could help gain a better understanding of which particular aspects of study abroad are most influential.

The criteria of network analysis

In order to analyse Japanese language learners’ social networks prior to, during, and after a study abroad period in Japan, I utilise Boissevain’s29 criteria for network analysis. Specifically, focus will be placed on:

Structural criteria:

- Network size — the total number of links in a network;

- Density — measurement of the potential communication between the individual network participants;

Interactional criteria:

- Multiplexity — diversity of links or role relations’ within a network that arise from participation in a number of different activity fields;

- Frequency and duration of interaction — indication of the investment of the people in the relation.

As this research focuses on L2 learners, attention will also be given to two additional criteria that are not covered in Boissevain’s framework: 5) language of interaction and 6) channels for interaction.

Methodology

Informants

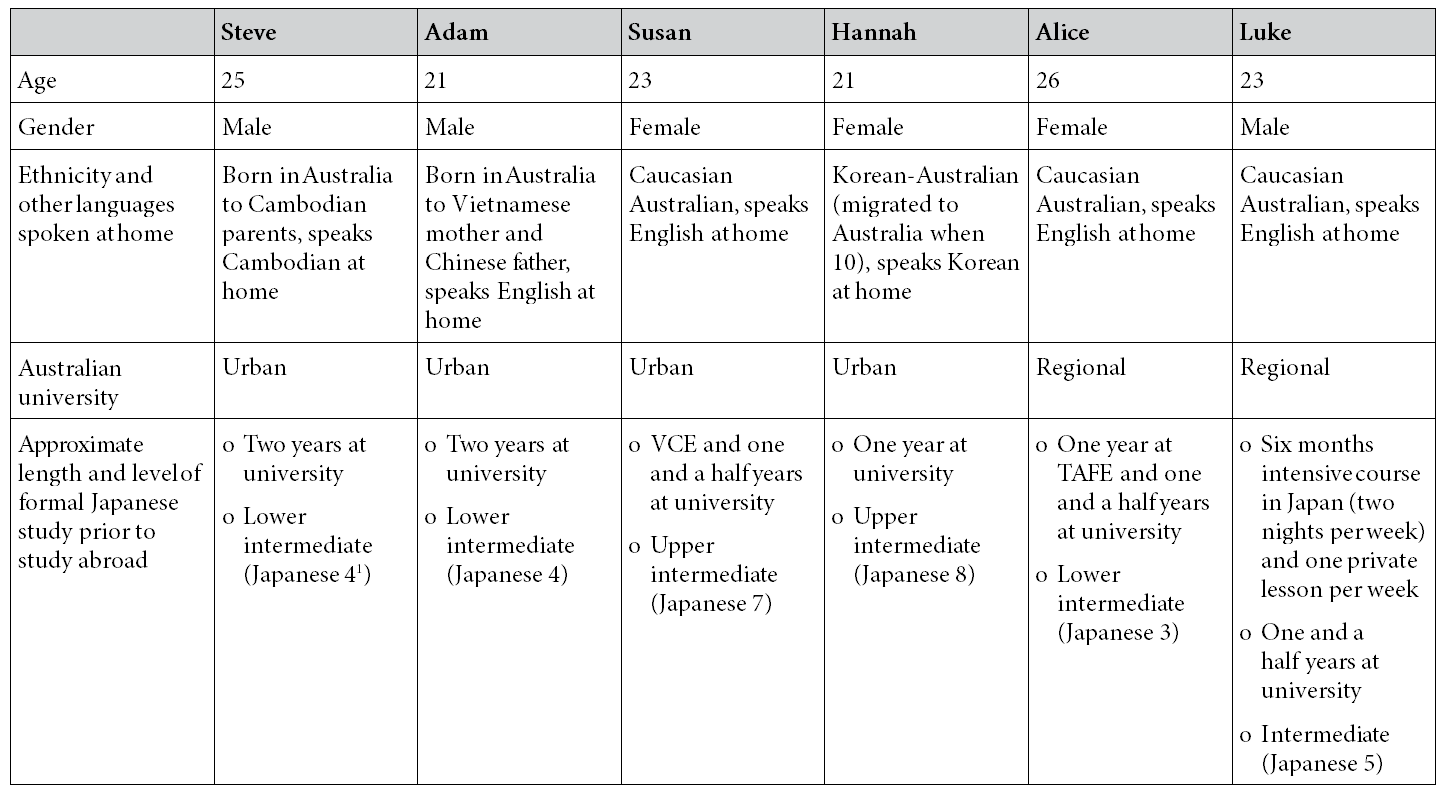

The informants in the present study consist of six Japanese language learners who have studied Japanese to the intermediate-advanced level. Two informants, Luke and Alice, attended a university in regional New South Wales, and the remaining four informants attended an urban university in Melbourne, Victoria. The intermediate-advanced level was chosen as students should have the proficiency necessary to engage in interactive contact outside the classroom.30

Table 1 below outlines the backgrounds of the informants in further detail. Attention must be drawn to the fact that whilst the informants from the university in Melbourne all returned from their study abroad period in 2010, the informants from the regional university, Alice and Luke, returned in 2006 and 2009 respectively. In the original study, Alice’s data was discussed in terms of two intervals: two years and five years post-study abroad. Due to space limitations however, only her two-year data will be discussed in this article. Luke experienced nine months of full time work in Japan prior to commencing university, and his case presents a longitudinal example of how networks may evolve over repeated visits to Japan.

Background questionnaire

Prior to interviewing the informants, they were required to complete a simple questionnaire to provide basic personal information as well as details about their Japanese language learning history and visits to Japan.

Semi-structured Interview

Semi-structured interviews were carried out in order to obtain detailed information about the characteristics of informants’ social networks and their study abroad experience. The questions were designed to elicit information concerning out-of-class interaction with Japanese speakers before, during, and after the study abroad experience in Japan, and to gain an understanding of the time they spent abroad and how this influenced their behaviour and beliefs. The interviews were approximately one hour in length, carried out in English and were audio-recorded and transcribed soon after completion.

Data Analysis

In the initial stages of data analysis, transcripts of the interviews were analysed for observable themes and reoccurring patterns to generate possible categories for coding the informants’ out-of-class interaction and network development. These emerged from the data as well as previous literature, and included categories such as context for network development’ and features of social interaction’. Comparative analysis of the informants’ data was then employed to examine the factors relating to the informants’ network development. This helped determine which factors were more generalisable, and which were more idiosyncratic in nature. Finally, Boissevain’s31 model of social network analysis was used as a framework to guide the analysis and discussion of the informants’ networks prior to, during, and after study abroad.

Results

The following sections introduce the characteristics of the six informants’ social networks with native Japanese speakers before, during, and after their study abroad period in Japan. As outlined in the methodology, prior to his study abroad experience, Luke had spent nine months living and working in Japan. The significant impact on his subsequent networks in both Australia and Japan means his data cannot be directly compared to the other informants and will thus be discussed as a separate case study.

Characteristics of social networks pre-study abroad

Structural Characteristics

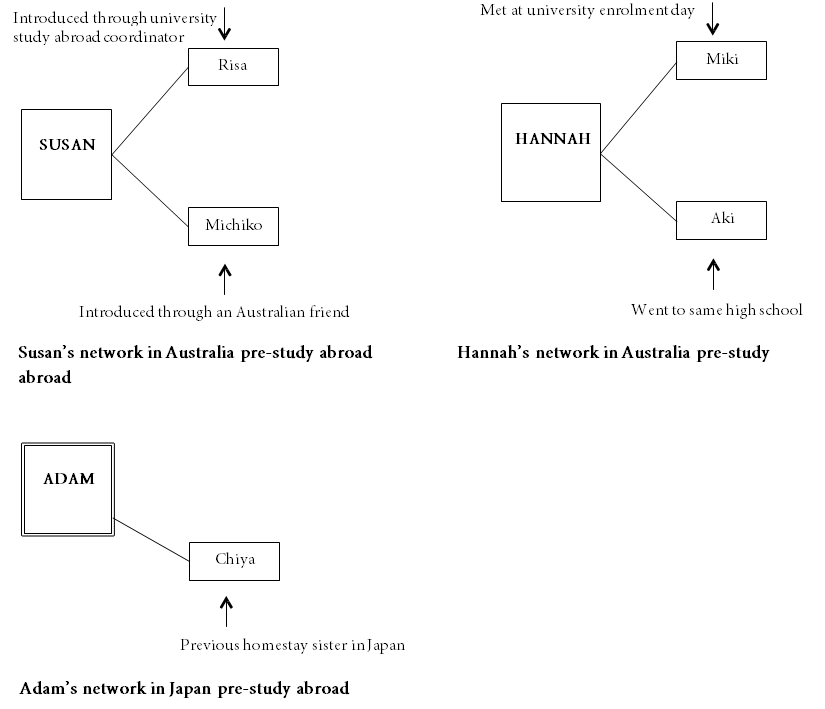

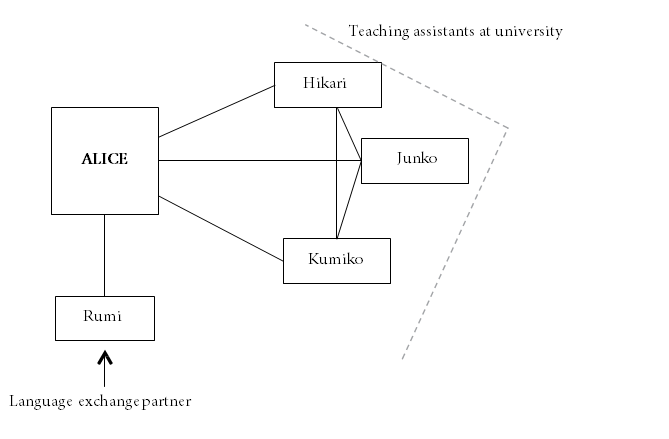

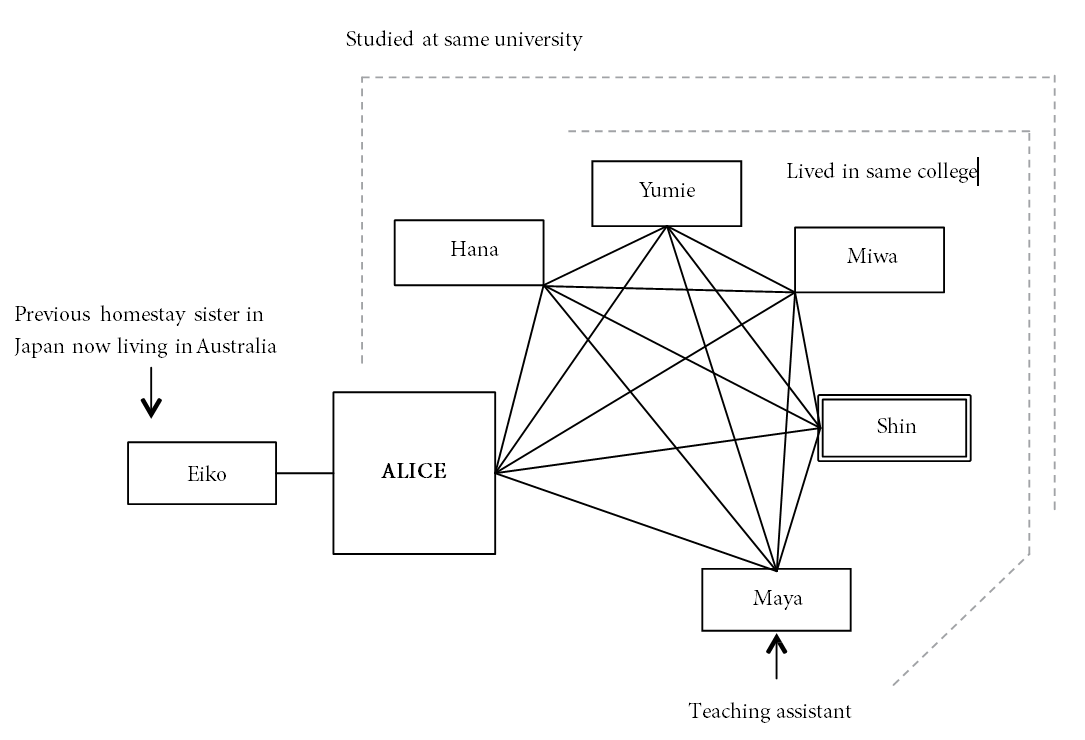

The informants’ networks pre-study abroad are depicted in Figures 1, 2 and 3 below. Gender is indicated with a double-lined box for male, and single-lined box for female. The figures also indicate the relationships between the informants and their network participants, or the activity fields where they first met.

Figure 1 — Urban university informants’ networks pre-study abroad

As can be seen, the informants’ networks pre-study abroad were relatively small (Steve had zero network participants). Whilst it was anticipated that informants living in a city with a greater Japanese population would have larger Japanese networks than the regional informants, it was actually an informant from the regional university, Alice, who had the largest number of network participants. A key difference in opportunities for network development is that students at the regional university appear to establish closer relationships with their Japanese teaching assistants.

Alice’s network in Australia was also denser than those of the urban informants’, and she mentioned that her interaction generally occurred within a group of teaching assistants and students. She also had a language exchange partner, however, which indicates that she had opportunities for one-on-one communication. The sparseness of the urban informants’ networks indicates that their interaction would occur as one-on- one communication.

Interactional Characteristics

In terms of multiplexity’, data revealed that the social relations most informants had with native speakers prior to their study abroad were uniplex, that is, covered a single role as friend. For Alice, however, the teaching assistants were key persons in her network and held two different social roles concurrently, as language tutors and as friends.

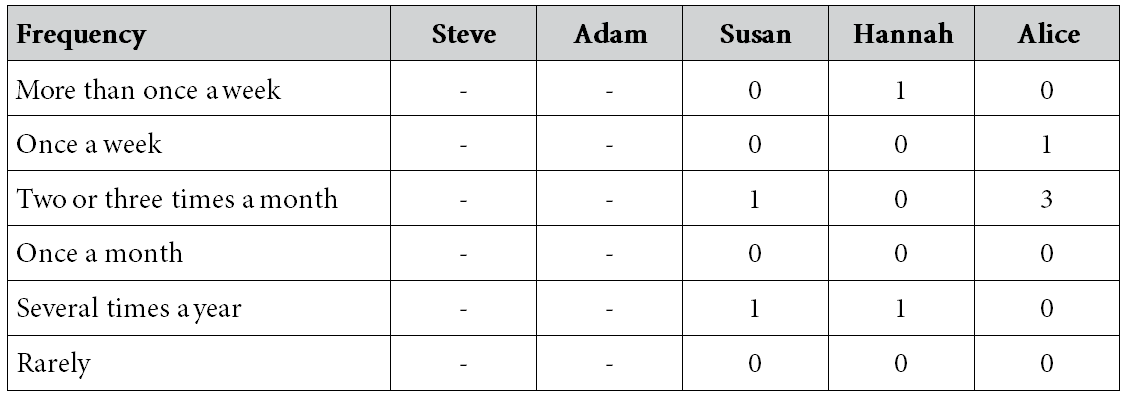

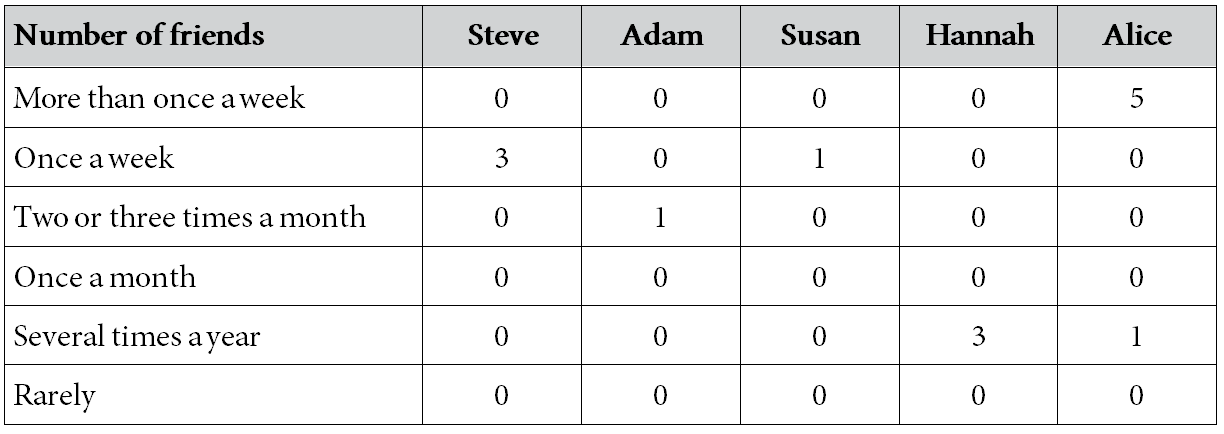

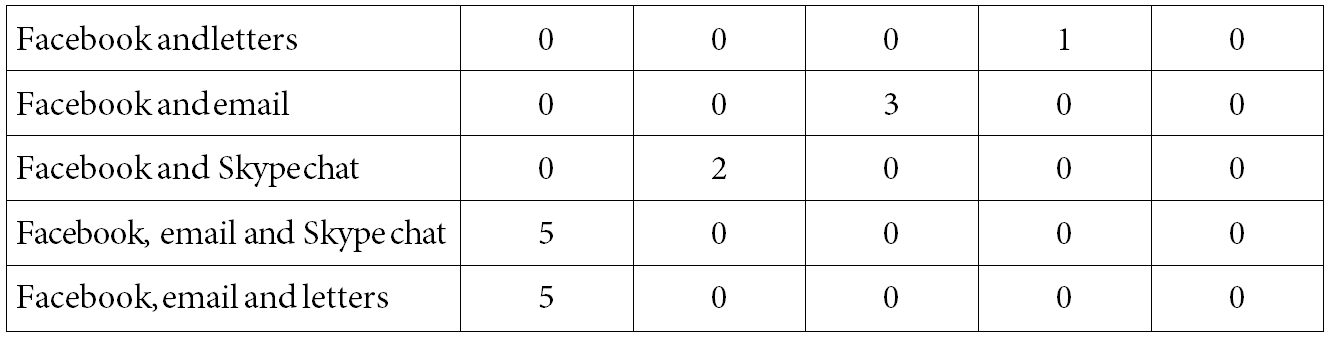

The frequency of contact between the informants and their network participants in Australia is shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2 — Frequency of interaction with network participants in Australia pre-study abroad

It can be seen that the informants who had native speaker network participants in Australia all interacted with at least one of them several times a month or more. Analysis of the interview data indicates that regular routine and locational proximity are two factors likely to impact frequency of interaction. Furthermore, Adam and Alice both indicated that they interacted with their network participants in Japan several times a year.

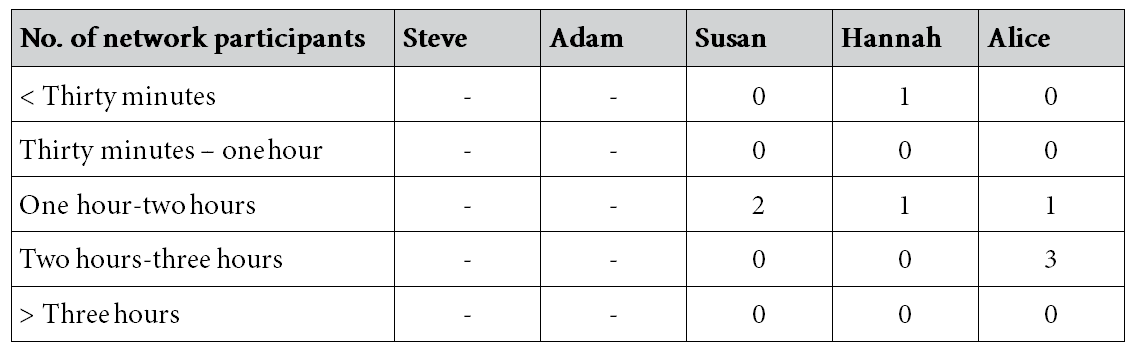

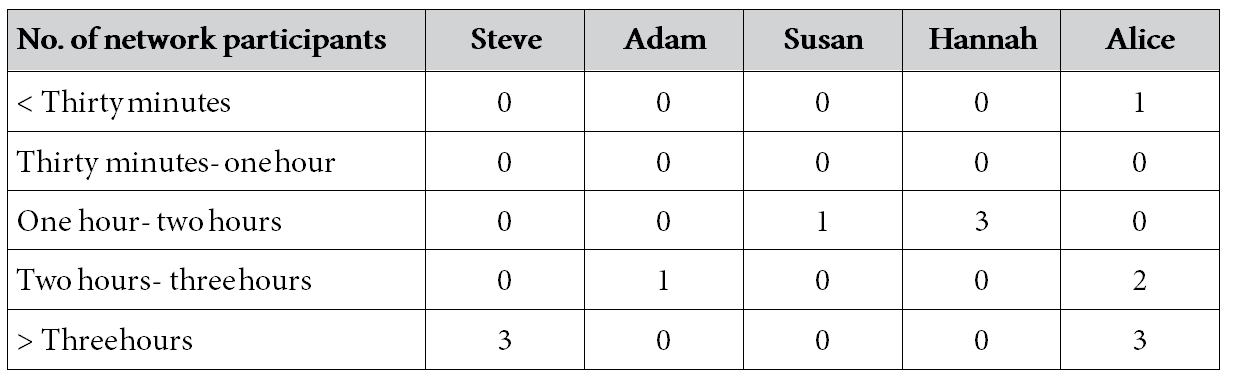

Table 3 shows how long, on average, the informants spent with their network participants in Australia when they came into contact with them prior to study abroad. Each of these informants met with at least one of their network participants for one to two hours or more, indicating substantial engagement.

Table 3 — Duration of interaction with network participants in Australia pre-study abroad

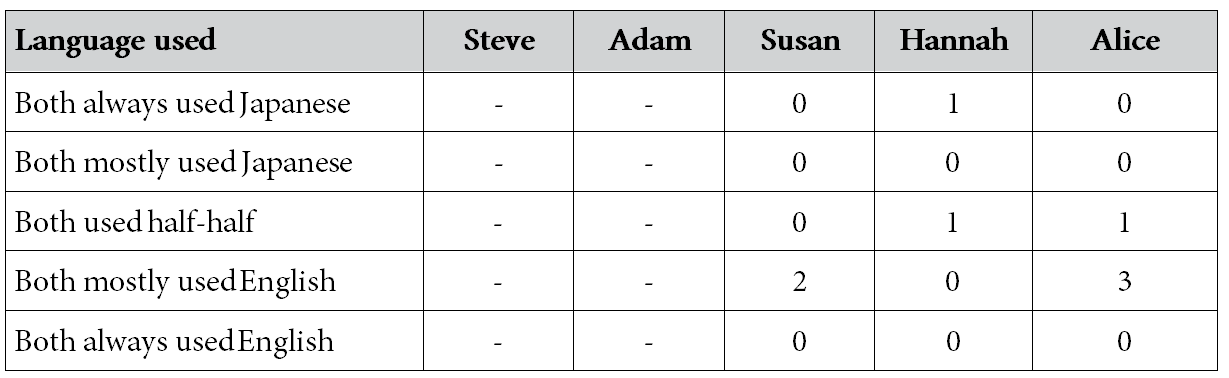

Concerning channels for interaction, Susan and Alice only mentioned having face-to-face interaction with their network members in Australia prior to study abroad, whilst Hannah also mentioned having Facebook contact with her friend from high school. As shown in Table 4 below, there was a trend to use either half English-half Japanese, or more English when conversing with the majority of network participants. For Susan and Hannah, this appeared to be reflective of their lack of confidence in using Japanese.

Table 4 — Language use with network participants in Australia pre-study abroad

In regards to networks in Japan, Adam only interacted with his network participant via emails written in Japanese. Alice interacted with her two network participants in Japan via emails and letters, however these were written primarily in English. Alice explained that this was because English was the language their relationships were based on, as she had met both of these people before she commenced her Japanese studies.

Network development during study abroad

Contexts for network development

During their study abroad periods in Japan, it seems that the informants’ opportunities for network development with native speakers were concentrated around several key contexts; student dormitory, homestay, university tutor system, university classes, and university clubs/circles.32

During their time abroad, Steve and Susan both lived in dormitories housing Japanese and international students, whilst Adam, Hannah and Alice lived in dormitories exclusively for international students. The latter informants’ opportunities for meeting native speakers were immediately constrained by institutional rules regarding who could reside in the dormitory, which meant that they only developed foreigner networks in this domain. Furthermore, the data indicates that because study abroad students all share a similar situation, they have an instant rapport, which meant that it was much easier for the informants to develop friendships with other study abroad students compared to Japanese native speakers. Susan commented that she hardly ever saw her two Japanese neighbours, and although Steve claimed to make two Japanese friends in the dormitory, most of his time was spent with the other study abroad students.

Adam, Steve and Alice participated in short-term homestays during their study abroad. For Steve, the homestay experience appears an important factor in his network development with native Japanese speakers, and he remained in contact with his homestay family at the time of the interview. Adam mentioned that he did not maintain contact with his family as they did not have internet access. Alice commented that she got put with a really really old family and it was just strange’, and did not maintain contact with them either.

Steve and Alice both participated in a tutoring system that was offered by their universities. Steve commented that their role was to mainly help you with your Japanese work. But sometimes you didn’t have any work that you needed help with, so you just talked, or we’d have coffee’. For both of these informants, it appears that this type of program offers a beneficial starting point for network development and interaction with local students as they both met other Japanese students through their tutors.

For study abroad students in Japan, two different types of classes are generally offered by universities: Japanese language classes, and other regular’ classes open to local and study abroad students. Whilst Adam, Alice and Steve claimed to make several local student friends from regular classes, Hannah and Susan did not enrol in any classes with local students and so did not have any opportunities for network development in this domain.

With the exception of Steve, all of the informants took part in university club or circle activities with the goal of making native speaker friends and accessing opportunities to use Japanese. These activities were especially important for Hannah and Susan, as this was where they appeared to make all of their native speaker friends and was their primary source for Japanese interaction. Susan mentioned that she received the impression that Japanese people don’t even make friends outside their circle… it really tended to be that your circle or your club was like your social group’.

Structural Characteristics

The informants indicated that it was very difficult to recall the names of all the local students they were in contact with during their time abroad, making it impossible to give entire network figures. In terms of density, however, a few trends emerged.

Firstly, participation in clubs/circles led to the development of especially dense sections of networks. The informants claimed to interact exclusively within the club/ circle and did not meet up outside of those events, indicating the high frequency of group interaction. Whilst Alice and Steve claimed to interact with their tutors one-on- one, Steve mentioned that it was common for many of the study abroad students and their tutors to have lunch together on campus.

Compared to the local student networks, however, the foreigner networks developed during their study abroad period had exceptionally high density. Alice, for example, stated that because they lived together and attended the same classes, study abroad students are constantly lumped together, and it’s really difficult to break out of that social group’. The high density of the foreigner networks may have impacted the degree to which they engaged with Japanese native speakers, reflecting the findings of Ayano.33

Interactional Characteristics

Whilst Hannah only seemed to develop uniplex relationships with her local friends in Japan, it appears that the majority of informants managed to develop at least some relationships with local students that were multiplex in nature. Steve, for example, held multiplex roles with one network participant as classmate, close friend, and travel companion. He also had a part-time job in the international building at university, where he knew Riko as one of the exchange program staff, as well as his boss. Adam developed one local relationship through another international student, and this local friend then became a classmate whom he would often see outside of class.

It appears that increased frequency and duration of interaction with network participants whilst in Japan was important for the development of more meaningful relationships. Susan, for example, indicated it was because she saw her Tennis Circle members frequently that she developed friendships she still maintains today. In contrast, Alice explained that the class-like, rigid structure the Basketball Club applied to their events and members’ social lives did not click’ for her and, because she had other social engagements, her attendance diminished over time.

Hannah stated that she felt as though she was really bonding with the other members of the Shamisen34 Circle during the longer periods of time spent together after going to a nomikai,35 talking in a relaxed atmosphere. Furthermore, Hannah and Steve both mentioned that it seems to take a lot longer to establish friendships with Japanese than it does with Westerners. This supports Neustupnདྷs claim that a more intimate level of friendship with the Japanese can only be entered on the basis of a long and well-established contact’.36

During the study abroad period, it appears that whilst the informants’ primary means of interaction with native speakers was face-to-face, the use of mobile phones was also common. Adam commented that emailing or texting was always a big part of the Japanese youth culture’, and all of the informants except Hannah claimed to utilise such channels with their network participants in Japanese.

Examination of the data indicates that language use with native Japanese speakers varied from informant to informant. Hannah and Susan both used Japanese exclusively with their Japanese network participants, and Adam also tried to use predominantly Japanese. Steve also claimed to use predominantly Japanese, with the exception of two network participants who practiced English with him and used half English, half Japanese. Alice however had a different experience, as outlined in her interview excerpt below:

I thought that I would have to speak Japanese to get by but it just did not work like that… I think I tried for the first few months [to use Japanese with native speakers], like I tried really hard but then I just stopped fighting it. Because you know I just realised that I’m there for a year, I really should be able to get something out of this’.

Alice’s tutor always spoke to her in English, and she also explained that whilst the regular’ classes afforded opportunities for network expansion, because they could be run in either English or in Japanese, a lot of the kids in there were pretty heavily into studying English’.

In regards to the foreigner networks that existed, a recurring theme was that English was generally used when interacting with students of Western countries, and Japanese was used when interacting with students from Asian countries. Adam frequently socialised in a small group with a Korean and Chinese friend who also lived in the dormitory, where they only used Japanese as this was the stronger language between them. Susan and Hannah, however, indicated that the majority of their foreign friends were more comfortable with using English and that it was important to be able to truly express their emotions in their native language.

Characteristics of social networks post-study abroad

The following section gives details of the characteristics of the informants’ social networks post-study abroad. As the informants have spent different durations of time post-study abroad, however, this must be taken into consideration when interpreting results.

Structural Characteristics

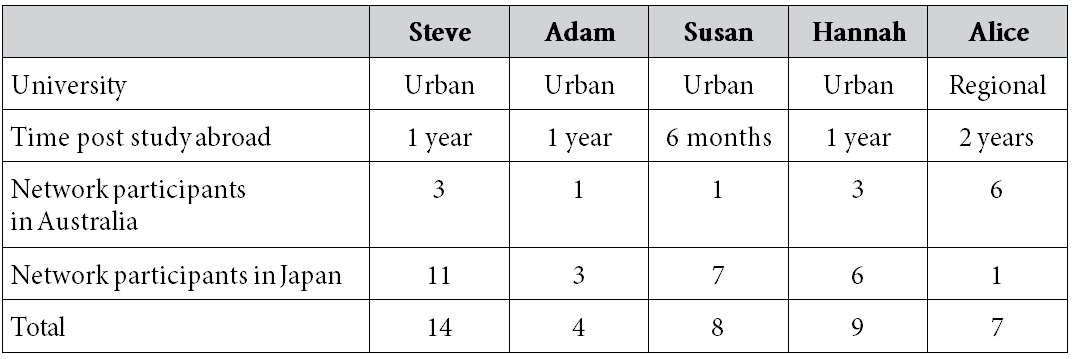

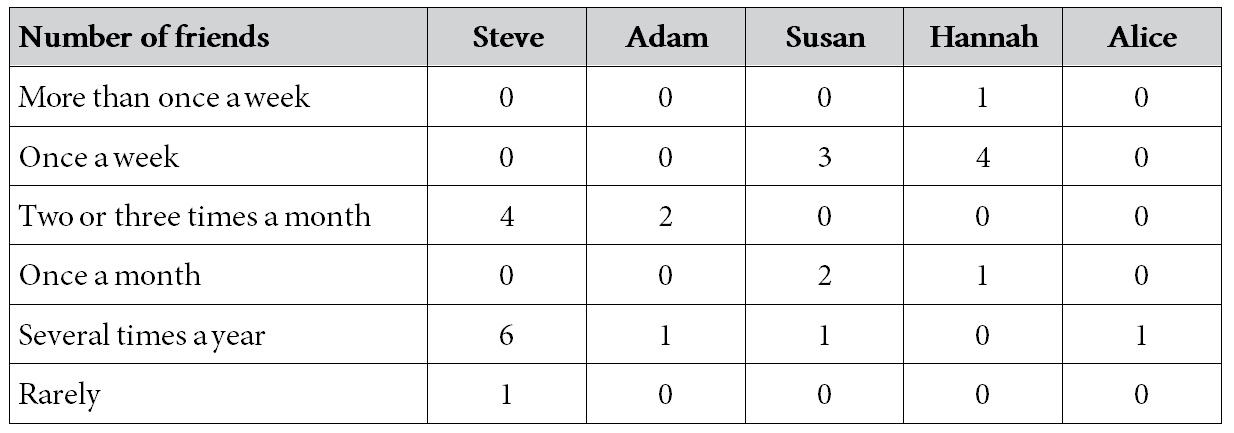

The size of the informants’ networks post-study abroad is shown in Table 5 below.

Table 5 — Number of Japanese network participants post-study abroad

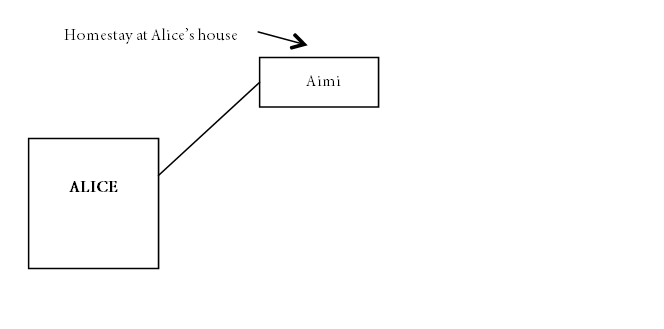

As expected, all of the informants’ social networks with Japanese people increased in size after their study abroad. Whilst informants’ networks in Australia did not appear to increase as much as anticipated, there was a significant increase in the number of network participants in Japan, which were primarily facilitated through their study abroad experiences. Alice is an exception, however, claiming that whilst she tried to maintain contact with the friends she made on study abroad initially, it never really stuck’. She made most of her close Japanese friends after she returned from study abroad, and although she no longer has the largest total network size post-study abroad, she still has the largest number of network participants in Australia, despite being at a regional university with a smaller local Japanese community.

Alice observed that the small number of Japanese students at this university meant they kind of needed to expand their group but still keep it somewhat comfortable’. Furthermore, the high density within the native speakers meant, in the case of Alice’s conversation partner, that she just needed someone she could vent to without having to worry about the other Japanese finding out’. It therefore appears that because the Japanese community at the regional university was so small, it may have been more important for native speakers to seek out non-Japanese interactants, thus enhancing opportunities for Japanese learners to develop native speaker networks.

The interview data suggests that there are a number of different contexts for learners to meet Japanese native speakers at the urban university, however, that students’ individual situations impacts the degree in which they utilise these opportunities. Adam mentioned that post-study abroad he doesn’t use as much Japanese as he’d like to, and that if he were still studying Japanese, he would make more effort to interact with native speakers outside the classroom.

Furthermore, Steve and Susan both mentioned that they were busy with other commitments. However, Susan did sign up for the university language exchange program, which offers her opportunities to use Japanese outside the classroom. Hannah also appears to have a higher level of L2 commitment than the other informants. She stated that post-study abroad, I started to be very active in Japanese community, in small meetings, seminars, I tried to engage as much as possible’. She also facilitated the commencement of a Japanese-English conversation group that is held weekly at the university and also attends a conversation club in the city, where there are people that she regularly meets but does not contact outside of club hours.

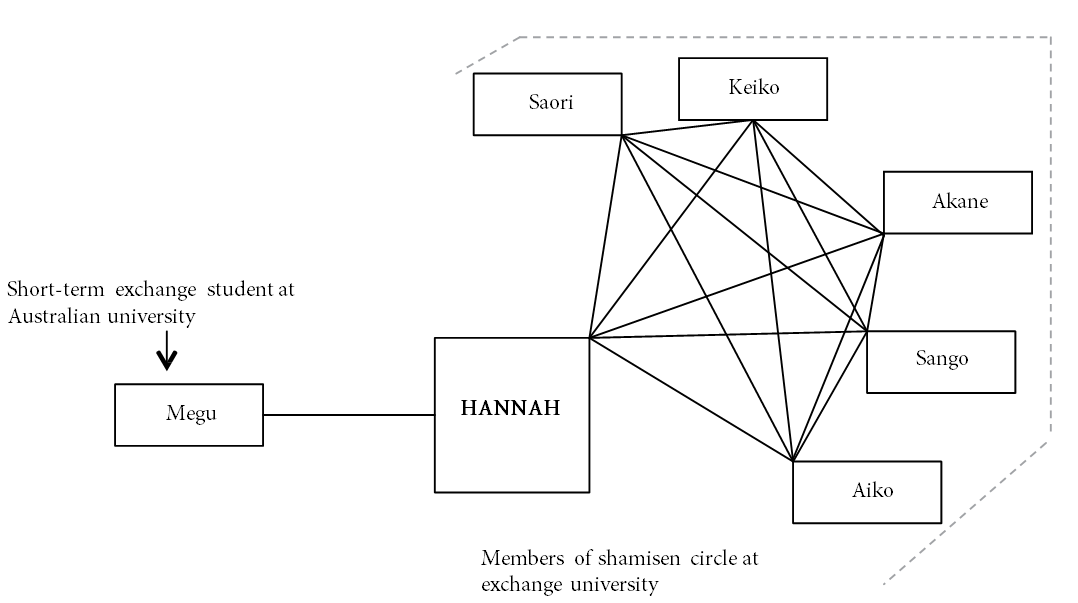

Figure 4 below depicts the urban university informants’ networks with Japanese native speakers in Australia post-study abroad.

Figure 4 — Urban university informants’ networks in Australia post-study abroad

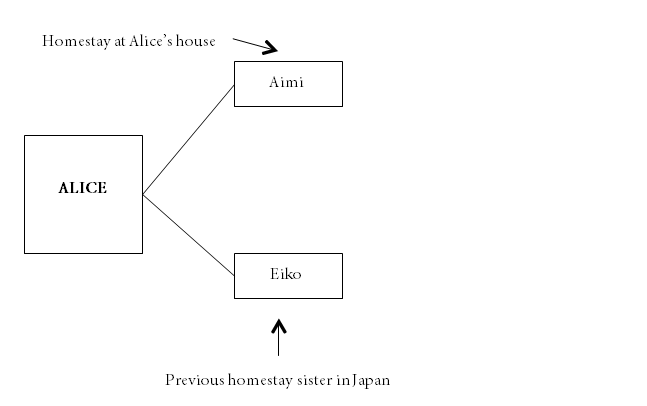

Whilst Adam and Susan’s networks remain sparse and only offer opportunities for one-on-one interaction, two of Hannah’s network participants knew each other, as did all of Steve’s, indicating a higher likelihood of group interaction that they did not have access to pre-study abroad. As depicted in Figure 5 below, Alice developed a relatively dense network after she returned to Australia. Maya appeared to be a key person in Alice’s network development, as she just kept meeting Japanese people through her’. It therefore appears that in regional areas where the Japanese communities seem to be particularly dense and tight-knit, forming a relationship with one key person may initiate quite rapid association with a number of other contacts.

Figure 5 — Alice’s network in Australia post-study abroad

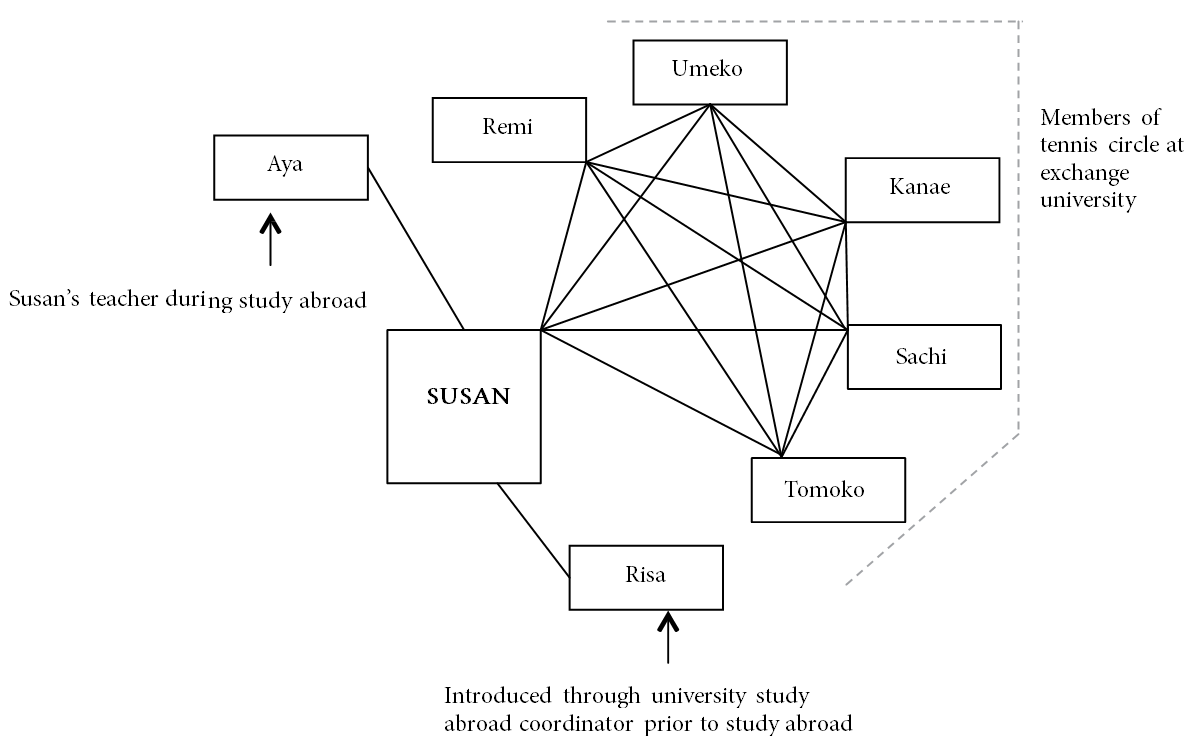

Hannah’s, Steve’s and Susan’s networks in Japan post-study abroad are shown in Figure 6, 7, and 8 respectively. For each of these informants, the study abroad period enabled them to develop and maintain dense networks with native speakers in Japan that they did not have beforehand.

Figure 6 — Hannah’s network in Japan post-study abroad

Figure 7 — Steve’s network in Japan post-study abroad

Figure 8 — Susan’s network in Japan post-study abroad

However, Adam and Alice only maintained contact with a small number of people in Japan. Their networks in Japan post-study abroad appear to remain sparse, and of similar configuration to their pre-study abroad networks, as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 below.

Interactional Characteristics

With the exception of Alice, the social relationships developed with native speakers in Australia post-study abroad appear to remain uniplex. As previously shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, the majority of the informants’ relationships were formed within the university setting with fellow students. Adam, Hannah and Steve’s network participants only appeared to have the social role of friend or acquaintance, whilst Susan’s network participant was a language exchange partner. Four of Alice’s network participants held multiplex roles of close friend and neighbour, and one also held simultaneous roles of close friend, neighbour, and teaching assistant. The other informants however, maintained contact with network participants in Japan who had multiplex roles, which suggests an affordance offered by the study abroad environment that may be more difficult to achieve in Australia.

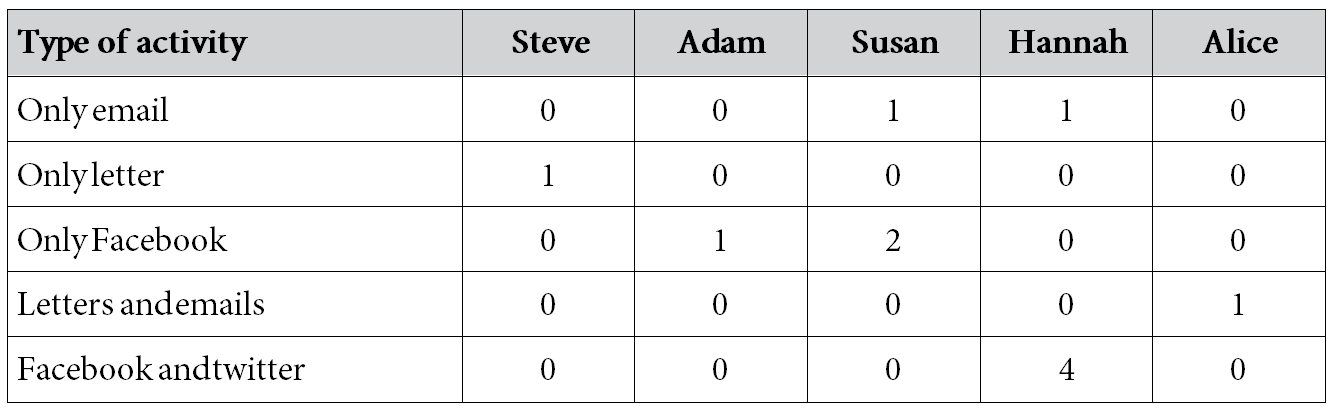

As shown in Table 6 below, with the exclusion of Hannah, all of the informants have more frequent contact with their network participants post-study abroad than they did pre-study abroad.

Table 6 — Frequency of interaction with network participants in Australia post-study abroad

Hannah explained that she now meets one of her network participants from pre-study abroad times less frequently, as they no longer attend the same university campus. Alice claimed to meet her network participants the most frequently, which may have been facilitated by the fact that the majority of them lived in the same university residence. This suggests the advantage of locational proximity for more frequent contact, as described in Tooby & Cosmides.37

As shown in Table 7 below, the most frequent duration of interaction was for between one and three hours, which shows a general increase compared to the pre- study abroad duration of contact. Alice is shown to have had interaction with one of her network participants for less than thirty minutes at a time, however, a lack of proximity meant this interaction was via letters or emails.

Table 7 — Duration of interaction with network participants in Australia post-study abroad

With the exclusion of Alice, the informants’ frequency of interaction with network participants in Japan is also significantly higher post-study abroad.

Although Alice only maintained contact via emails and letters, the other informants claimed to make use of CMC, including Facebook and Skype. Compared with the informants’ channels for interaction pre-study abroad, it can be seen that the study abroad period may have offered a gateway into L2 online interaction with native Japanese speakers.

Facebook appears to be the most common channel for interaction amongst the informants, not only with Japanese network participants, but also with study abroad peers. In the past half-decade, Facebook has quickly risen as a social service utilised by university students for both the maintenance and development of a range of social ties.38 Hannah explained that being on Facebook means keeping in contact with people, not necessarily talking to them for a long time’. As the informants are highly likely to be using Facebook to interact with other people locally, and throughout the world, this may incidentally lead to maintenance of contact with Japanese network participants. The dynamics of Facebook therefore merit further investigation that was beyond the scope of this study.

In regards to the informants’ interaction with network participants in Australia post-study abroad, it was primarily, if not exclusively, face-to-face. Alice was the only informant to mention utilising any other channel for interaction, which included phone calls, text messages, emails and Facebook.

All of the informants indicated that they returned from study abroad with a higher level of confidence in both themselves and their Japanese abilities. Hannah for example explained:

I guess I feel more comfortable about how to approach a Japanese person, what kind of phrases or level of politeness I need to use. I mean if you feel confident in the language, the more comfortable you feel to interact with the person from that country’.

This also relates to the reoccurring theme of improved sociolinguistic and cultural competence, which meant the informants were better able to relate to Japanese students in Australia once they returned.

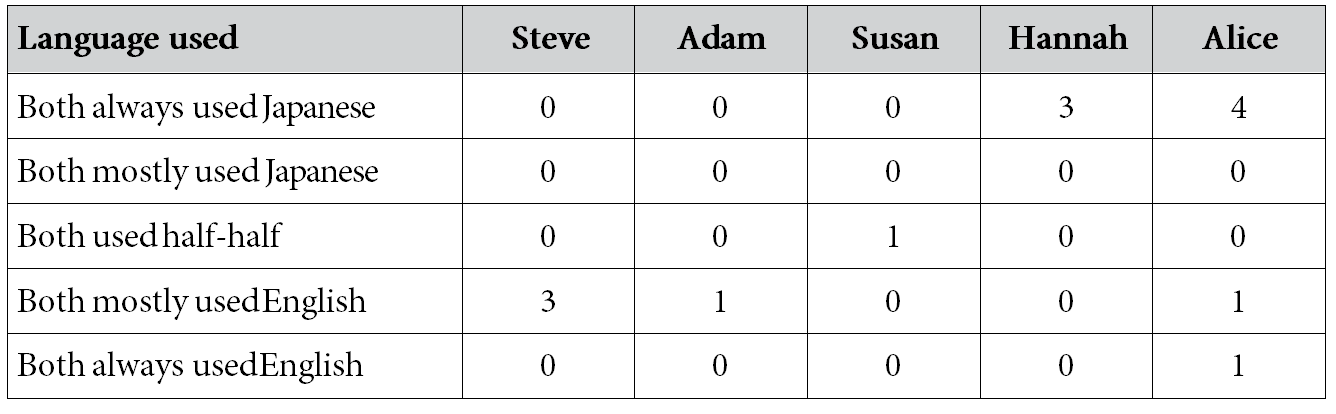

The informants’ language use with their network participants in Australia is also shown in Table 10 below.

Table 10 — Language use with network participants in Australia post-study abroad

All of the informants use more Japanese within their networks post-study abroad. Steve however stated that if Japanese have come to Australia, especially to learn English… I try to use English, unless they want to speak to me in Japanese’. Alice also claimed to leave the language choice up to her interactants for the same reason, however, the majority of her network participants preferred to use Japanese with her.

The data shown in Table 11 below, however, indicates that Steve, Adam, and Hannah claimed to maintain contact with their network participants in Japan using only Japanese, as did Susan for all but one of her network participants. In this case, Susan explained that because her interactant emailed her in English, she would also respond in English.

Table 11 — Language use with network participants in Japan post-study abroad

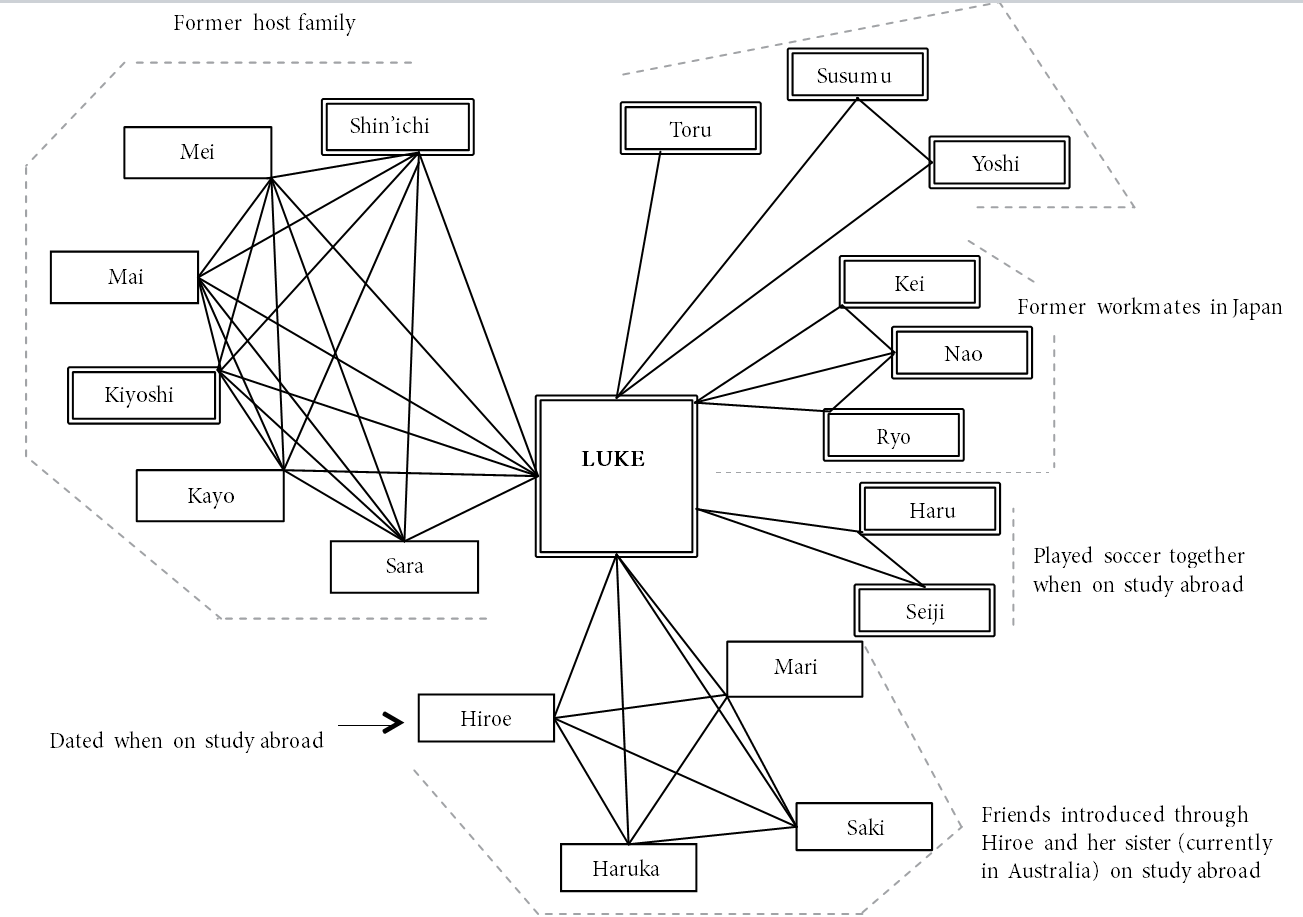

A case study of a frequent sojourner: Luke

Luke offers an interesting addition to the other five informants as he has made multiple sojourns in Japan. The following sections will trace his network development with native Japanese speakers over four different periods.

Period 1: Working in Japan

It appears that Luke’s experience working at a wedding company in Japan had a significant impact on his networks with native speakers. During this period, his main network development was formed around two key domains: work and his homestay families. As Luke did not know any Japanese before this experience, it appears that his younger host sister and a work colleague had important multiplex roles. Both spoke minimal English and would help him with his Japanese, indicating roles of language tutor alongside host sister/colleague, and friend. Importantly, Luke did not mention having access to co-nationals, and stated: If I’d been in a situation like a study abroad where I was put like in the same situation as a bunch of foreign students, I would’ve gone and spoken English’.

Period 2: Post-working in Japan, pre-study abroad

Figure 11 below depicts Luke’s network that he maintained in Japan after his working holiday. Luke claimed to maintain contact with his homestay family almost weekly via email and Skype, and with three of his workmates and three clients via email several times a year.

Figure 11 — Luke’s network in Japan post-working holiday

Figure 12 below depicts the network that Luke developed in Australia after his return.

Figure 12 — Luke’s network in Australia post-working holiday

It can be seen that the majority of his relationships were formed at his university, and the relatively high density of the regional university’s Japanese community was, once again, a benefit. This meant that after an initial Japanese contact was made, many others were introduced to Luke through this key person. Like Alice, Luke also developed multiplex relationships with two of the Japanese teaching assistants at his university. Luke also mentioned that working in Japan taught him a lot about how to get along with Japanese people and communicate well’, which may also explain why he developed a much broader network than Alice pre-study abroad.

Luke claimed to participate in a wide range of activities within his network, and to meet with all the network participants several times a week, for a duration of twenty minutes to several hours depending upon the activity. In terms of language usage, Luke would initially use English, but once his network participants knew he could speak Japanese, they tended to primarily use Japanese.

Although this network for Luke is considered pre-study abroad, it offers insight to the impact of an in-country experience in Japan, and thus more closely equates to the other informants’ post-study abroad networks. The following two periods indicate how his networks in both Australia and Japan continued to change with subsequent sojourns.

Period 3: Study abroad

As Luke’s study abroad experience was his second long-term sojourn in Japan, his experiences were somewhat different to those of the other informants. He indicated that having been to Japan before and being able to speak a fair amount of Japanese meant that he did not fall into the comfort zone’ of primarily socialising with study abroad peers and using English. He stated: before I went on study abroad, I thought, ”I’m going to go to Japan and study Japanese. I’m going to do my best to hang with Japanese and use as much Japanese as possible”’.

Luke indicated however that the dormitory was a major social setback during the study abroad period. Despite living amongst both local and international students, he said that the dormitory was a Japanese friend desert’. Furthermore, his classes were with other study abroad students, and he commented that the only way you could avoid sort of being in that situation where you’re only speaking English is if you’re rude and ignore everyone and don’t hang out with them’.

Luke did, however, gain entrance into a Japanese social group quickly, and it appears that the support of the study abroad network was not as important for him as it was for the other informants. He claimed to socialise with six of his closest Japanese friends almost daily, often meeting in-between or after classes. One of these friendships developed into a romantic relationship, and Luke claimed to spend a significant amount of time at his girlfriend’s house. He was the only informant to have a Japanese relationship of this nature, where his girlfriend was likely to hold multiple social roles.

Luke also played in a futsal league once a month, where he met two of his closest friends. However, he stated that they were so lazy they never turned up’, and were thus friends outside of that’. Conversely, he said that although the Soccer Circle he joined trained and played together on weekends… those guys in that circle were sort of exclusively friends within soccer, not really outside’. Furthermore, Luke also claimed to receive phone calls and messages on his phone from his prior-homestay family, and visited them as well as his former colleagues and clients a few times during holidays.

With the exception of his girlfriend, therefore, it appears that the majority of Luke’s relationships formed during study abroad were uniplex in nature. However, they all seem to be very close and mutual, which correlated with frequent and prolonged interaction. Whilst there was a general consensus amongst the other informants that it was easier to form relationships with other foreign students as opposed to working on getting relationships with Japanese people’ (Alice), this did not appear to be the case with Luke. He stated that he did not feel there was too much difference in the nuances between Australian and Japanese people’, and that during study abroad, he made two of the best friends he has ever had.

Period 4: Post-study abroad

As outlined in the methodology, Luke had just returned from a subsequent three-month holiday in Japan not long before his interview. Luke’s current network maintained in Japan post-study abroad is shown in Figure 13 below.

Figure 13 — Luke’s network in Japan post-study abroad

It is evident that Luke has established a significantly large network in Japan maintained through frequent contact and repeated sojourns. He explained that it’s got to the point now, when I’m in Australia it’s not for extended periods of time, like I’m always itching to get back to Japan and meet up with those guys’. Looking back at Figure 12, however, it is interesting to note that Luke no longer maintains contact with any of the network participants he had at his Australian university, except for Maya who remains in Australia. Whilst he did not indicate the reason why, one explanation could be that he did not return to university after his study abroad. Another could be that perhaps the earlier relationships in Australia were due to locational convenience, whereas the ones developed during his sojourns in Japan were based more so on similar interests.

Figure 14 below indicates that Luke’s current network in Australia is relatively small compared to that in Japan.

Figure 14 — Luke’s network in Australia post-study abroad

This network is also less dense in nature, and each of the relationships are uniplex. Furthermore, it appears that Luke currently has less frequent interaction with these network participants than he does with the majority of his participants in Japan. When concluding his interview, Luke stated:

I guess interaction with friends is a huge, a big part of my maintenance of Japanese. Especially Skype and talking on the phone, there’s really no substitute for a conversation… if I’ve got any queries over certain grammar or any sort of Japanese questions I’ve always got those guys I can just send an email to or ask them on Skype ”what’s this mean?” or ”is this right” or whatever’.

Luke’s continued maintenance of contact with his former host family, work colleagues, and friendships developed in Japan reinforces the importance of utilising modern technology to maintain networks established whilst abroad. His case has exemplified how networks may evolve over time, and that they offer ongoing opportunities for friendship development and Japanese use and learning.

Concluding discussion

This study has investigated how characteristics of Japanese language learners’ networks with native speakers differ before and after a study abroad period in Japan. Although the results show that the informants each offer unique cases, there were a few overall trends. Whilst all of the informants’ total network size increased after their study abroad period, (with the exception of Luke after his first trip to Japan), their networks in Australia did not expand or increase in density as drastically as anticipated, and Susan’s actually decreased in size. The urban informants’ networks also appear to remain uniplex post-study abroad.

There was, however, an overall increase in informants’ frequency and duration of interaction, as well as more frequent use of Japanese post-study abroad. It was also found that the informants’ time spent in Japan lead to perceived increases in linguistic, sociolinguistic, and cultural competence, higher confidence in themselves and their Japanese capabilities, and greater empathy with Japanese students studying in Australia. These factors may have contributed to more effective Japanese interaction. However, all of the informants indicated that they respect the fact that Japanese students are in Australia to learn English, which sometimes compromised their degree of Japanese usage. Negotiation of language choice in interaction, therefore, appears to be an important factor for analysis, but was beyond the scope of this study.

Comparing this group of informants’ post-study abroad networks to those of Kurata’s39 informants’, it would seem that Luke’s network in Australia post-working holiday may be more representative of students’ returning from an in-country experience. It could be due to various individual factors such as discontinuation of Japanese study, or prioritisation of other commitments, that the other informants’ networks did not expand as much as one would expect. All of the informants’ current networks in Japan, however, are considerably larger than pre-study abroad, which is one of the most significant findings of this study.

The network participants in Japan were found to provide ongoing sources for Japanese interaction through a wide range of channels including letters, email, Skype and Facebook, which the majority of informants were not exposed to pre-study abroad. Technology therefore plays a crucial role in the maintenance of learner’s ongoing overseas networks, and lessens the impact of geographical distance. This is particularly important for students who do not develop extensive networks in Australia.

Interestingly, the regional informants were found to have larger, denser, and more multiplex networks, as well as more frequent and prolonged contact with native Japanese spea

- Kurata, Foreign Language Learning and Use’, p. 6. ↩

- Segalowitz & Freed, Context, Contact and Cognition’, p. 174. ↩

- Milroy, Language and social networks’, p. 178. ↩

- See for example, Kato & Tanibe, Tanki ryuugakusei no gakushuu nettowaaku’; Pearson-Evans, Recording the journey: Diaries of Irish students in Japan’; Amuzie & Winke, Changes in language learning beliefs’; Ayano, Japanese students in Britain’; Isabelli-Garcia, Study Abroad: Social Networks, Motivation and Attitudes’. ↩

- Kurata, Communication networks of Japanese language learners and second language acquisition’. ↩

- See for example Segalowitz & Freed, op. cit.; Magnan & Back Social interaction and linguistic gain during study abroad’; Isabelli-Garcia, op. cit. ↩

- Lapkin et al., A Canadian interprovincial exchange’. ↩

- Regan, The acquisition of sociolinguistic native speech norms’. ↩

- Isabelli-Garcia, op. cit. ↩

- Hernandez, The relationship among motivation, interaction, and the development of second language oral proficiency’. ↩

- Freed, op. cit. ↩

- Segalowitz & Freed, op. cit. ↩

- Segalowitz & Freed, op. cit. ↩

- See for example Tanaka, Japanese students’ contact with English outside the classroom’; Kato & Tanibe, op. cit.; Pearson-Evans, op. cit.; Amuzie & Winke, Changes in language learning beliefs’. ↩

- Kato & Tanibe, op. cit.; Pearson-Evans, op. cit. ↩

- Ayano, op. cit., p. 26. ↩

- Rivers, Is Being There Enough?’; Mendelson, Hindsight Is 20/20′; Tanaka, op. cit. ↩

- Rivers, op. cit., p. 493. ↩

- Schmidt-Rinehart & Knight, The Homestay Component of Study Abroad’; Rivers, op. cit.; Isabelli-Garcia, op. cit.; Kinginger, Language learning in study abroad’. ↩

- Magnan & Back, op. cit.; Hernandez, op. cit. ↩

- Tanaka, op. cit., p. 50. ↩

- Umeda, Ukeire kikan o motanai hi-nihongo bogowasha no nettowÄku zukuri’; Tomiya, Nihonjin to kekkonshita gaikokujin josei no nettowÄku’. ↩

- Morofushi, Communities of practice and opportunities of developing language socialization’, p. 49-50. ↩

- Kato & Tanibe, Tanki ryÅ«gakusei no gakushÅ« nettowÄku’. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Pearson-Evans, op. cit., p. 45. ↩

- Pearson-Evans, op. cit., p. 45. ↩

- Ibid, p. 108. ↩

- Boissevain, Friends of friends’. ↩

- Freed, Language learning in a study abroad context’, p. 465. ↩

- Boissevain, op. cit. ↩

- An extra-curricular circle’ in Japan is similar to a club, however less serious or competitive in nature. ↩

- Ayano, op. cit. ↩

- Japanese string instrument. ↩

- Drinking party. ↩

- Neustupnà½, Communicating with the Japanese’, p. 49. ↩

- Tooby & Cosmides, Friendship and the banker’s paradox’, p. 136. ↩

- Ellison et al., The benefits of facebook ”friends”’. ↩

- Kurata, Communication networks of Japanese language learners’. ↩