[REVIEW] Okinawans Reaching Australia

Reviewed by

![]()

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7686-3652

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7686-3652

Published August, 2020

Pages 109-112

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21159/nvjs.12.r-03

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney and Shannon Whiley, 2020

New Voices

in Japanese Studies

Volume 12

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2020

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The history of Japanese immigration in Australia remains an area that is not widely known. As a result of the White Australia Policy, only a relatively small number of Japanese had immigrated to Australia by the time of World War II, and many of their stories are yet to be explored. In Okinawans Reaching Australia, John Lamb seeks to bring light to Japanese immigration history by delving into the records of Okinawans who lived and worked in Australia at the height of the pearling industry. Building on his previous work, Silent Pearls: Old Japanese Graves in Darwin and the History of Pearling (2015), which examined Japanese workers in the Australian pearl-diving industry prior to World War II, Lamb has produced a meticulously researched account of the history of Okinawan immigration to Australia in the early-to-mid twentieth century. Okinawans Reaching Australia draws on archival documents to build a detailed picture of the early Okinawan presence in Australia which is largely focused on the pearling communities of Darwin, Thursday Island and Broome.

Lamb seeks to identify the Okinawans who came to Australia between 1905, when the first known Okinawan arrived in Australia, and the 1960s, when many returned to Japan following the decline of the pearling industry. The book is structured chronologically, covering the early pre-war migration, war-time internment and post-war return of Okinawan citizens. As the pre-war Okinawan community in Australia was comparatively small, the book focuses on the circumstances of Okinawans’ arrival and employment in Australia after the war. The Okinawans chronicled in the book are all men. They generally worked in Australia as indentured labourers on fixed-term contracts for pearling companies and were granted temporary admission to Australia within the framework of the White Australia Policy. Pearling was dangerous and had long relied heavily on non-white indentured immigrants; notably, it was ”the only industry to be exempted from the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901″ (Martànez 2005, 127), which was the centrepiece of the White Australia Policy. Japanese pearlers, including Okinawans, made up the largest national group of labourers in Broome and on Thursday Island, and were considered to be strong workers (Sissons 2016, 9).

Lamb’s book examines the politics of Okinawan immigration to Australia. It highlights the part that Okinawan workers played in re-opening Australia to Japanese immigration after World War II, showing that the Australian government differentiated Okinawa from the rest of Japan to allow immigration to resume. This was seen by the Australian government as an attractive solution to an inconvenient problem: it was hesitant to allow Japanese immigration but faced pressure from the domestic pearling industry due to its reliance on the skilled labour of Japanese pearlers. Ultimately, the Australian government preferenced Okinawans but agreed to allow limited entry to pearlers ”from the Ryukyu Islands or Japan” (Lamb 2019, 40) due to a variety of reasons including the pearling industry’s established connections with regions outside Okinawa (namely, Wakayama). As a result, mainland Japanese labourers ended up arriving first, but some of the groundwork for their return was laid by the Australian government’s efforts to allow entry to Okinawans specifically.

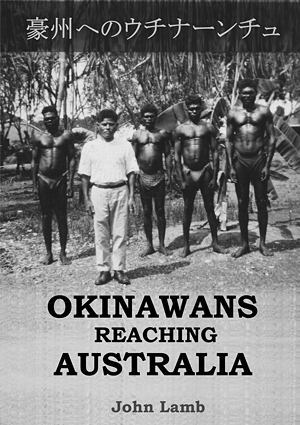

One of the highlights of Okinawans Reaching Australia is the range of high-quality photographs included throughout. Lamb has collected extensive photographic records of fishing vessels and divers at work, as well as a near comprehensive set of portraits of the Okinawan workers. The cover image in particular, which depicts Okinawan diver Kinjō Anki with four Tiwi men in 1932, is a great visual representation not only of early Okinawan experiences in Australia, but also of a diverse Australia under the White Australia Policy. Images, diagrams and descriptions of pearling vessels and equipment are used to give a clear indication of the work that Okinawan immigrants performed in Australia and the working conditions they experienced. These are complemented by profiles of individual Okinawan labourers that depict their lives and expeditions as pearlers. This dimension of the book brings the Okinawan pearlers to life, and is well suited to the large, A4 format.

The early chapters of Okinawans Reaching Australia contextualise these stories with a broad examination of Japanese immigration to Australia against the backdrop of the White Australia Policy and World War II. While there were only 16 known Okinawans living in Australia at the outbreak of World War II, 245 Okinawan residents of South Pacific island nations were brought to Australia for internment during the war. Their inclusion in the book is an important acknowledgement of pre-war Japanese emigration to the South Pacific. The internees were returned to Japan following the war, and no Okinawans are known to have been allowed to remain in Australia after the last were repatriated in 1946. However, later chapters reveal that some were eventually able to return as indentured labourers, including Kinjō Anki, who in 1955 was one of the first Okinawans to arrive after Japanese labourers were permitted to return post-World War II.

Chapter 4 examines this post-war re-introduction of Japanese and Okinawan immigration and delves into the political difficulties of re-establishing the pearling industry after the war. Lamb argues that the admission of indentured Japanese pearlers to post-war Australia was revived due to a push from the local pearling industries, which had suffered from a shortage of skilled labour. However, three main factors stalled and limited the admission of Japanese to Australia: anti-Japanese sentiment within Australia, Japanese fears of competition with its own pearling industry, and territorial issues stemming from Australia’s claim to the Arafura Sea off the northern coast of Australia (an area Japan had used for its own pearling prior to World War II). It was these factors, Lamb asserts, that led Australia to seek cooperation from the post-war US Administration in Okinawa to provide indentured workers for its pearling industry.

Chapters 5, 6 and 7 focus on the post-war pearling industry in Darwin, Broome and Thursday Island respectively, outlining when Okinawan divers returned to each region. Broome, which had had positive experiences with Japanese labourers and an integrated Asian community prior to the war, was the first to allow labourers from Japan to return. Although Okinawans were requested as a preference, time constraints and alleged falsities about the availability and performance of Okinawan labourers led to labourers initially being recruited from mainland Japan from March 1953. Darwin, seeing the successful re-introduction in Broome but having a population with much stronger anti-Japanese sentiment, became the first location to recruit Okinawans after the war, beginning in August 1955. In these chapters, Lamb incorporates detailed information on the pearling companies and the individual Okinawans who worked for them, making it both an excellent reference for historians and an interesting insight into how the pearling industry operated.

These later chapters also look at the broader picture of immigration and industry politics, utilising archival records. Pearling industry figures attributed the industry’s eventual decline to the alleged unsuitability of Okinawan labourers to pearl diving. However, these chapters put forth evidence that this assessment was largely spread by those with vested interests in indentured labour from mainland Japan, including pre-war businessmen who sourced indentured labourers and had established connections on the mainland. Rather, Lamb attributes the lack of early success by post-war Okinawan pearlers to factors such as insufficient knowledge of the specific locations of production beds, a natural decline of the industry due to depletion of resources, and reduced demand following the spread of plastic buttons. To illustrate this, the book draws on quotations and photographs of original government cablegrams and correspondence between master pearlers, pearlers’ associations, Australian and Japanese government ministers, ambassadors and other parties associated with recruiting pearlers.

Okinawans in Australia opens new avenues for further research into Japanese-Australian history. Lamb identifies two pearl divers from Thursday Island, Senshō Arakawa and Kyōzō Hirakawa, who were still alive at the time of the book’s publication, and the latter still lives on Thursday Island. There may be other angles from which to further explore the stories of these individuals and those of other early Okinawan immigrants to Australia, including experiences outside the pearling industry or in more recent contexts. There may also be further research opportunities in looking into the Australian government’s efforts to distinguish Okinawan immigration as separate from Japanese, and whether this had any impact on other industries and aspects of post-war immigration from Japan. As Lamb himself writes in the postscript, this in-depth examination may mark ”the beginning of a new exploration of the stories of these men” (100).

Okinawans Reaching Australia serves as an important record for historians and future generations, and contributes to the growing body of work on Japanese immigrant experiences in Australia. The immigration documented in the book occurred in relatively isolated communities in Northern Australia and few Okinawans from this period remained after the industry declined in the 1960s. As a result, post-war Okinawan pearl divers have largely been relegated to a footnote in Australian immigration history. In defying this trend, Okinawans Reaching Australia makes a significant contribution to the field of Japanese-Australian history by preserving the stories of early Okinawan immigrants and bringing an important piece of Australian history to light.

REFERENCES

Lamb, J. 2015. Silent Pearls: Old Japanese Graves in Darwin and the History of Pearling. Australian Capital Territory: Deakin.

Martànez, J. 2005. ”The End of Indenture? Asian Workers in the Australian Pearling Industry, 1901—1972.” International Labor and Working-Class History 67: 125—47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547905000116.

Sissons, D. C. S. 2016. ”The Japanese in the Australian Pearling Industry.” In Bridging Australia and Japan: Volume 1, edited by A. Stockwin and K. Tamura, 9—27. Canberra: ANU Press.

Shannon Whiley

Shannon Whiley graduated from The University of Queensland (UQ) in 2015 with an Arts Degree in Japanese and Asian Studies, and was awarded Honours in Japanese. After spending two years on the JET Programme, she now works in Brisbane for a Japanese government agency and intends to pursue further research. Shannon has contributed two publications to New Voices in Japanese Studies: a research paper titled The Experiences of Nikkei-Australian Soldiers During World War II (NVJS 10), and a review of the book Okinawans Reaching Australia (NVJS 12). She has also published her research in The Conversation.

(August 2020)