The gaijin at home: A study of the use of the word gaijin by the Japanese speech community in Sydney, Australia

Published January, 2011

Pages 32-56

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21159/nv.04.02

New Voices

Volume 4

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2011

Permalinks for references are available in the HTML version of this article.

Abstract

The word gaijin, typically glossed as foreigner’, has been the focus of academic interest spanning across several disciplines, ranging from studies in intercultural communication, discourse analysis, and discriminatory language. These studies have perhaps logically been confined to the context of Japan, as it makes sense to study foreigners’ in a context in which they are indeed foreign’. It may be by an extension of this logic that the use of the word gaijin has not been studied in contexts outside of Japan at all.

This study made use of a novel methodology of focus groups and follow-up interviews to capture the use of the word gaijin by members of the Japanese speech community in Sydney, to ascertain empirically how members of the community use the word gaijin, and in what contexts such usage occurs. The article identifies the interpretations of the word of native and non-native speakers of Japanese, and discovers two models of the use of the word gaijin.

Introduction

It is characteristic of communities to define themselves by stating what it is that they are not, and this is no less true in the case of some Japanese communities. The word gaijin (外人), typically glossed as foreigner’, or outsider’, is an example of this characteristic. Outside Japan, the word has become well known as a result of the boom in gaijin businessmen’1 during the 1980s and 1990s, and popular literary sources such as Clavell’s novel Gai-Jin.2 Within Japan, any long-term visitor is likely to become familiar with the word on a much more personal level.

While in general use the word gaijin is translated in English as foreigner’, the meaning of its composite characters gives it the literal meaning of outside-person’, or outsider’. Its composition can be compared with the word gaikoku-jin (外国人) foreign- person’, whose composite characters mean outside-country-person’. Both words are in common use in Japan, however it is the latter that is used in official documents and speeches. There is a growing debate in Japanese society over the legitimacy of the use of the former, gaijin, amongst a gradual removal of discriminatory language from the media and official sources.3 This has occurred in response to a movement against discriminatory language driven by minority groups such as the indigenous Ainu population, the burakumin, and ethnic Korean Japanese.4

Although aversion to the use of the word gaijin is not universal, it is significant. An early online survey of foreigners residing in Japan in 1996 found that 40% of respondents considered the word to be discriminatory or racist, with the remaining 60% either unsure or not bothered by the word.5 While studies of the word have commendably referenced aversion to its use and its occurrence in the public sphere, no empirical studies have been undertaken to establish the social function of the word, or indeed, the underlying attitudes towards its use by Japanese speakers. Regardless of whether the word is considered discriminatory by the speaker or the referent, the word gaijin is a clear expression of difference with complex and varying interpretations attached.

Less clear, is our understanding of how such difference is expressed by Japanese communities living outside Japan and the role that language such as the word gaijin plays in the expression of identity and community boundaries. In an effort to address this gap, this article will detail the results of a 2009 study on the actual use of the word gaijin by the Japanese speech community in Sydney, to determine the characteristics and function of such use.

The study was designed with two purposes. The first was to ascertain how the Japanese speech community in Sydney uses the word gaijin. The second was to identify the contexts in which the Japanese speech community use the word gaijin. As such, the study made use of five research questions in order to investigate the phenomenon of the use of the word gaijin in a foreign setting in the Japanese speech community in Sydney, Australia.

- Are members of the Japanese speech community in Sydney aware of their usage of the word gaijin?

2. a. In what key’6 do members of the Japanese speech community in Sydney use the word gaijin?

b. What functions7 are being achieved by the use of the word gaijin, if any?

3. a. Who in the Japanese speech community uses the word gaijin?

b. Who is being referred to by the use of the word gaijin?

4. a. What are the scenes and settings’8 in which the use of the word gaijin occurs?

b. What level of formality is associated with the use of the word gaijin?

5. In what ways is the usage of the word gaijin interpreted?

To improve our empirical understanding of the word gaijin the study made use of Hymes’ components of speech as a framework for developing the research questions as these are well established tools for sociolinguistic analysis.9 However, for the purposes of defining the social function of the word gaijin, this article will chiefly draw upon the conclusions of the study in relation to research questions 2b and 5 as these generated the richest and most illuminating data.

The article will first review the literature relating to the word gaijin, then detail the research methodology. The article will then identify interpretations of the word and discuss its function by developing two models of the word’s use.

Gaijin

While a basic definition of the word gaijin was provided above, this section will outline the existing literature regarding the word and the approaches used in its study. In doing so, the study can be located as addressing the general lack of consideration of the use of the word gaijin in a context outside of Japan, and as addressing a lack of empirical research pertaining to the word in general. A limitation of the present literature review has been the general paucity of research regarding the word gaijin, with a limited number of works dedicated to its study.

Literature related to the word gaijin spans several academic disciplines, ranging from studies in intercultural communication, discourse analysis and discriminatory language. Although these all differ greatly in their approach to the word, works in each of these disciplines have in common an exclusive focus on the use of the word within Japan.

Ishii’s10 study of gaijin represents the most substantial consideration of the word in the context of studies of intercultural communication. In tracing the Japanese concept of strangers’ through folklore as represented by tales of marebito and ijin, Ishii states that the word gaijin refers exclusively to those who are physically different from the Japanese (that is, white or black).11 This focus on physical difference as a definition of the word gaijin is shared by the bulk of the literature, however this is a statement that seems to be taken for granted with little or no empirical evidence.

A very different approach to the study of the word gaijin is that taken by Nishizaka, who uses a discourse analysis approach to argue that the identities and interpretations of gaijin, and hen na gaijin[12. hen na gaijin: Strange foreigner’ generally refers to a foreigner with a high competency in Japanese and an understanding of Japanese culture; Nishizaka, Doing interpreting within interaction’, p. 246.] are achieved through interaction. Nishizaka analyses a recording of a radio interview between a Japanese host and an exchange student, in which the host uses the word gaijin to assert his own identity as Japanese in a situation where the exchange student displayed an unexpected proficiency in reading kanji (Chinese characters).12 Nishizaka’s analysis uncovers another dimension of the word gaijin that is not based purely on appearance, but that is rooted in the expression and assertion of identity by the speaker. However, the scope of the study is limited in its analysis of a single discourse, and it is difficult to determine to what extent other factors, such as the physical appearance of the exchange student, may have prompted the use of the word gaijin.

The third study of the word gaijin is the discriminatory language research approach, featured in the analysis of Gottlieb.13 She offers a brief discussion of the word gaijin in two studies,14 in which growing discontent towards the use of the word is documented from the 1980s, in particular the activities of human rights campaigners in Japan such as the ISSHO Kikaku group that have highlighted discrimination towards foreigners.15 Within the discussion of the word gaijin, Gottlieb’s analysis is congruent with that of Ishii and Nishizaka in regard to the referents of the word and its use.16

The above studies of the word gaijin have perhaps logically been confined to the Japanese context. It makes sense to study foreigners in a place where they are indeed foreign’. It may be an extension of this logic that the use of the word gaijin has not been objectively studied in contexts outside of Japan at all.

The use of the word gaijin to refer to foreigners outside Japan has been documented briefly by Tsuda17 in a study of Nikkei Japanese18 in Brazil, where it is claimed that the word is used in the Japanese community to refer to those outside of the community. Tsuda’s study is not focused on the language use of the community in Brazil, therefore little detail is provided about the circumstances in which the word is used. However, Tsuda’s reference to the use of the word outside Japan supports the need to further investigate the language use of Japanese speech communities abroad.

The above brief review of the literature related to the word gaijin highlights two main points. First, study regarding the word gaijin is limited in comparison to the study of words referring to other minority groups in Japan, and second, that there are several persistent generalisations regarding the referents and use of the word gaijin, that are recurrent without sufficient supporting empirical evidence.

Research Methodology

While early sociolinguistic studies focused on an ethnographic approach based on participant observation,19 in recent research interview data have often formed the basis of analysis.20 However, this study utilised focus groups and follow up interviews (FUI) as the primary sources of data related to the use of the word gaijin in the Japanese speech community. This was due to the breadth of the data that could be gleaned from this methodology, and because of the well known criticisms of co-construction occurring in the more traditional interview methodology.21 Ethics approval was granted by the university at which the study took place in May 2009.

Sampling

Six native speakers of Japanese (NSJ) and three non-native speakers of Japanese (NNSJ) were chosen from the Japanese speech community in Sydney. NSJ participants were chosen to reflect a range of communicative competency with non-members of the Japanese speech community, and divided between three focus groups. NNSJ participants are included in the study in order to consider the use of the word gaijin by NNSJ members of the speech community, and to provide a greater breadth of viewpoints to be discussed by participants in the focus groups.

26 NSJ potential participants were asked to complete a questionnaire, providing details on their personal background pertaining to their membership of the Japanese speech community in Sydney and their exposure to contact situations with non-members of the community. The questionnaire collected information pertaining to the length of residence in Australia, and language use. Respondents were asked to rate their English ability, and the frequency with which they use the English language. Participants were able to select from one of four grades of English ability, which were adapted from the definitions of bands 4 (Limited User), 5 (Modest User), 7 (Good User) and 9 (Expert User) of the 9 band International English Language Testing System marking scale.22

Six potential NNSJ participants were also asked to complete a questionnaire to establish the extent of their interactions with the Japanese speech community in Sydney, their Japanese proficiency and general language background. The potential participants included both native and non-native speakers of English. As with the NSJ questionnaire the NNSJ questionnaire collected information on residency in Australia and Japan, and the respondent’s language background, querying the frequency of Japanese language use, languages spoken at home and at the workplace. Respondents were asked to rate their Japanese ability, and the frequency with which they use the Japanese language.

Participants were able to select from one of four grades of Japanese ability. The definition for each of these grades was adapted from the competencies explained in the definitions of bands 4 (Limited User), 5 (Modest User), 7 (Good User) and 9 (Expert User) of the 9 band IELTS marking scale for consistency, and as the explanations for each grade reference general communicative ability rather than English specific language skills.

Selection of participants

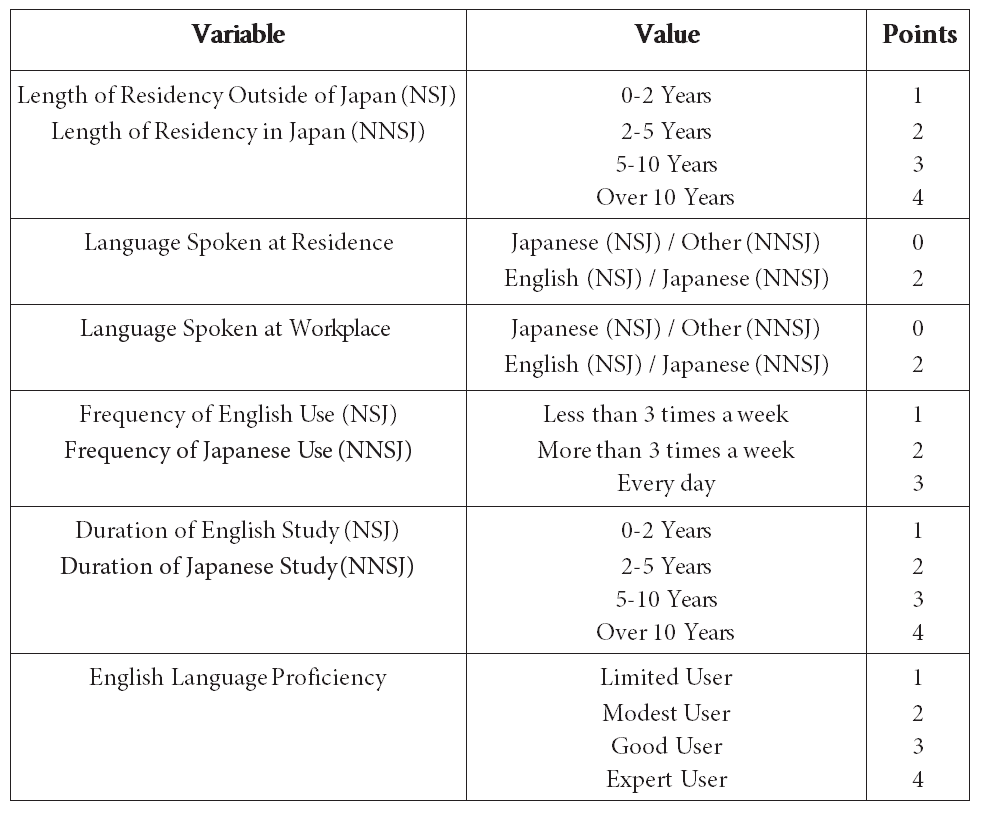

A simple points based scale was devised23 to rate NSJ questionnaire respondents in their level of experience in interacting with non-members of the Japanese speech community, and to rate NNSJ respondents in their level of experience in interacting with the Japanese speech community. This was done in order to consider the effect of such experience upon the use of the word gaijin by research participants. The scale rates participants based on their length of residence outside of or in Japan, the language spoken at their place of residence and workplace, length of language study and their self-assessment of their non-native language ability, in order to place them into corresponding focus groups. The points scheme is detailed in Table 1 below.

Table 1 — Contact Situation Experience

The purpose of the point scheme above was to provide a comparative measure for the level of experience that different potential participants had had in interacting with non-members/members of the Japanese speech community by taking into consideration several different factors that are difficult to compare separately. The weighting of each item was determined by altering the figures to such that the point tallies for individual questionnaire respondents were sufficiently distributed to allow for comparison. The higher the point score of a participant, the more experienced they may be considered to be in interacting with non-members/members of the Japanese speech community. It is assumed that generally, higher levels of exposure to contact situations are likely to have resulted in a greater number of experiences with the potential to alter the participant’s perceptions of non-members of the community.

Focus Groups

Focus groups have been chosen as the primary source of data as they have the potential to capture the use of the word gaijin as it occurs between members of the speech community, and to limit the involvement of the facilitator in the construction of responses. Additionally, the participant focus of the format allows participants to probe and challenge each other’s views, a practice that seldom takes place in conventional interviews.24 This provided valuable insight into the thought processes behind the use of the word.

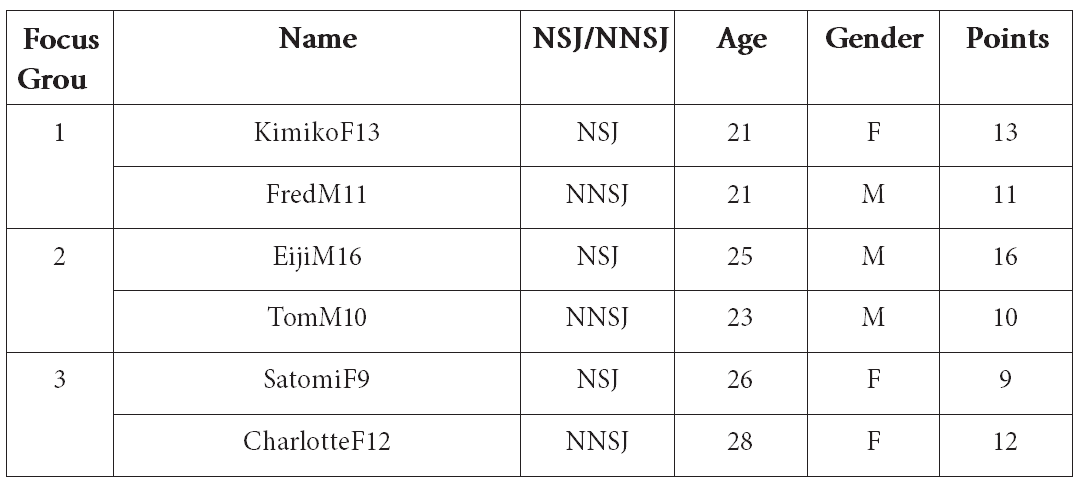

The allocation of participants to focus groups is detailed in Table 2 below.

Table 2 — Focus Group Participants25

The focus groups took place in a private room at the university, and were audio and video recorded for transcription and analytical purposes, and for the purpose of review during the FUIs to follow. In each group, participants were asked to view three short films.26 Participants were encouraged to discuss the contents of each film as well as any personal experiences or observations regarding interaction with non-speech community members. Some prompts were offered by the facilitator where discussion faltered.

There are two reasons for the use of film in the focus groups. First, the film was used to provide an initial focus for what could have been a challenging topic for some of the participants, especially given the identity of the facilitator as a person who may be seen as a referent of the word gaijin. Second, the film was intended to provide a common reference point for analysis of participants across the three groups, as data from each group was expected to vary greatly.

The films were obtained from the Youtube website, using the search term ”外人” (gaijin). Films were selected that contained the word gaijin in conversation, to act as a starting point for participants to discuss the use of the word. The films chosen were also comical, to create an atmosphere in which participants could discuss the word freely.

Follow-Up Interviews

In this study the FUI served as an opportunity for participant and researcher to explore and interpret the data gained from the focus groups, and had three main purposes. First, the FUI was used to allow participants an opportunity to verbalise the thought processes or lack thereof that accompanied particular actions in the data, and in confidence.27 This is important as a means of circumventing the possible effect of social expectations in shaping participant’s responses with other members of the speech community. Second, the FUI allowed both researcher and participant to explore any extra-linguistic behaviour that may occur in the focus group data.28 Third, the FUI was a mechanism by which the researcher could clarify and validate existing data.29

The FUI is a one-on-one interview that is conducted after the transcription of the original data has been completed. The FUIs were conducted within a week of the original data collection, so that the participant’s recollections of the event were clear, and were audio and video recorded for the purpose of transcription and analysis.

The FUI gauges the participant’s expectations of the study, and awareness before, during and after the study. The facilitator focuses on the participant’s awareness of their own behaviour and thought processes, norms and deviations on norms, evaluation of behaviour and behaviour of other participants, while viewing footage of the data. Progression through the footage is controlled by the participant, although the facilitator may direct the participant’s focus to a particular point where desired.30

Description of Data

The data collection methods outlined above yielded a rich array of data in two forms, the transcripts of participants’ speech, and the visual record of the participants’ non-verbal communication, as captured on video. The transcripts provide a record of the occurrence of the word gaijin in the speech of participants, while video data contain a vivid and visual record of participant’s non-verbal communication, including para-language such as pauses, fillers and intonation that accompanied their speech.

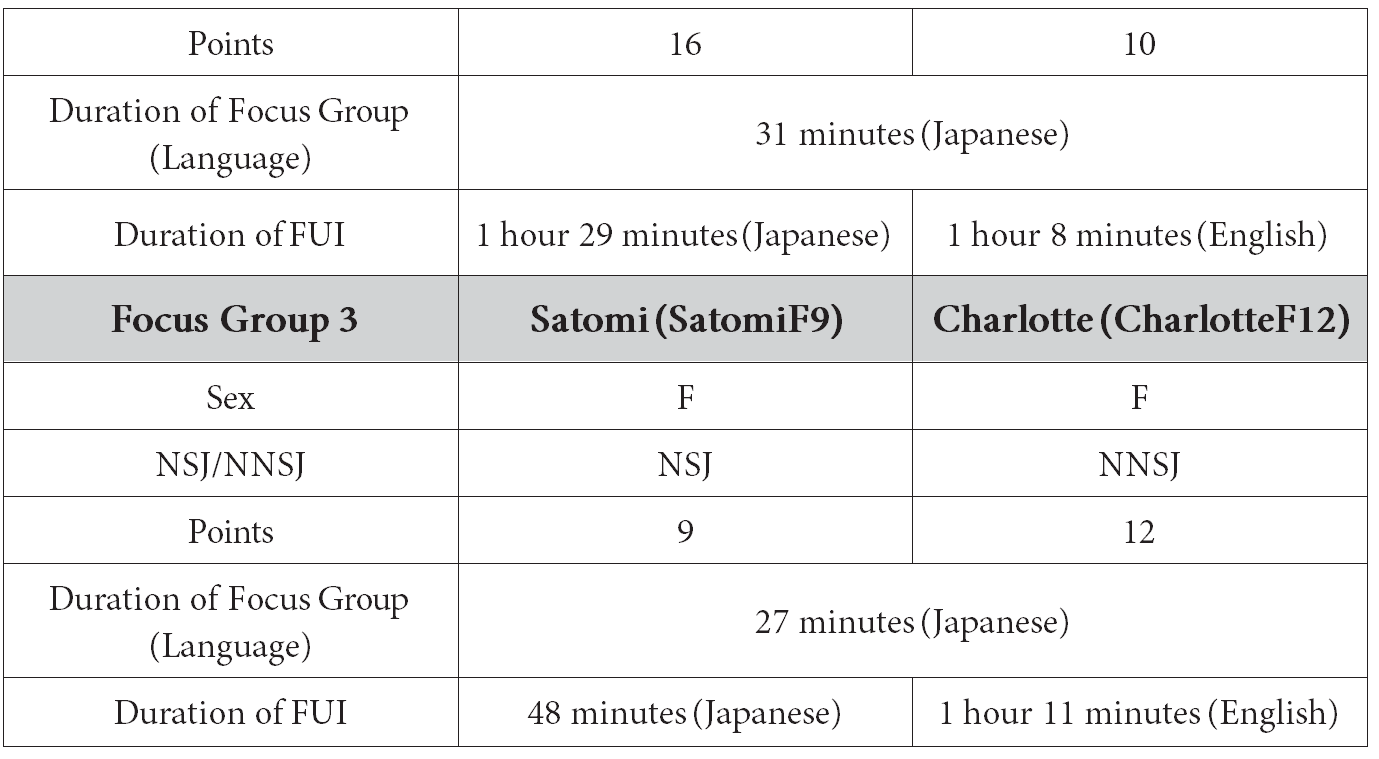

Each of the focus groups took place with two participants, an NSJ and an NNSJ. The participants of each focus group are detailed in Table 3 below.

Table 3 — Details of Focus Groups and Follow-up Interviews (FUI)

Eleven interpretations of the word gaijin were identified in total across the three focus groups, which are discussed in detail below. These interpretations referred to particular physical, behavioural and linguistic characteristics that were associated by the participants with referents of the word.

Focus Group 1 (FG1)

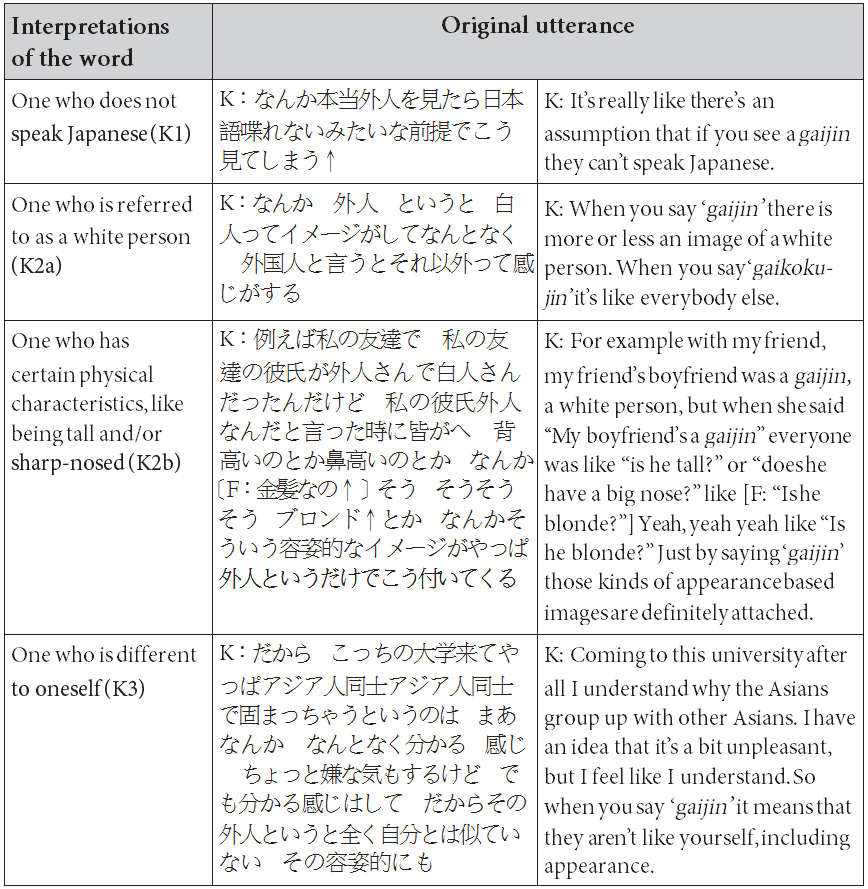

Five interpretations oftheword gaijin were identified in FG1. Intotal, three interpretations of the word gaijin were identified during FG1 by KimikoF13. The first is that a gaijin does not speak Japanese (K1), the second that the word refers to a white person (K2a), with particular physical characteristics, such as height and a large nose (K2b), and the third, that the word refers to a person different to oneself (K3). These characteristics are not mutually exclusive, as they lend themselves to the description of a particular group of people. The three characteristics of gaijin identified by KimikoF13 are congruent with the definitions of the term identified in the preceding literature.31 KimikoF13 was forthcoming and hesitated little in identifying the above characteristics, suggesting that these were associations that she was readily aware of and that she had considered before.

Based on the above three interpretations of the word gaijin by KimikoF13, the word gaijin can be defined as an index as it is used here by a NSJ to point to a particular group, the members of which are physically and linguistically different to the speaker. The word gaijin indexes this difference, but is also limited to those with the above characteristics.

Two interpretations of the word gaijin were identified by FredM11. The first was a strong nuance of non-acceptance of the referents of the word gaijin when used by NSJ (F2). When used by NSJ, the word is interpreted as indicating non-acceptance: an interpretation which was partly based on negative encounters with the word while living in Japan. FredM11 spoke of the issue emotionally in FG1 (see extract in Table 4), and elaborated in his FUI that he felt strongly about the word to the point that he would disassociate himself from those who continued its use. The issue of acceptance was not an interpretation raised directly by KimikoF13, however, parallels can be drawn with the notion that a gaijin is somebody who is different to oneself. It would seem to be this notion of difference that contributes to an understanding of the word as being associated with a lack of acceptance by the speaker.

The second interpretation of the word identified by FredM11 offered a very different understanding of the word gaijin to that offered by KimikoF13. In contrast to the definition of gaijin as a distinctly white person with certain physical characteristics, the definition offered by FredM11 was purely that of foreigner’, a word stripped of the context of physical appearance and linguistic ability. While the conflation of the word gaijin to foreigner’ may seem to be deeply related to the notion of non-acceptance discussed above, FredM11 claimed in the FUI that he did not associate the word foreigner’ with any negative connotation. It was revealed by FredM11’s utterances in the focus group and in his FUI that in his use of the word foreigner’, FredM11 saw the referents of the word as shifting contextually based on time and place, as opposed to the fixed Japanese context constraint implied by KimikoF13’s use of the word gaijin. Thus, the second interpretation given here can be considered separate to the first interpretation listed above.

The two interpretations identified by FredM11 cast two different lights on the indexing function of the word gaijin exhibited by KimikoF13. In addition to indexing difference, as an NNSJ, FredM11 interprets the word gaijin as indexing acceptance, and sees the word as a term used to estrange the referent from the speaker. In describing the second characteristic of the word, FredM11 provides a different interpretation of the word gaijin, expressing an ideal’ interpretation of the word as a deictic index of the foreigner’ relevant to the speaker, and separate from its Japanese context.

Table 4 summarises the interpretations of the word gaijin shared by the participants of FG1, along with the original utterance and English translation.

Table 4 — Interpretations of the word gaijin identified by KimikoF13 and FredM11

K: KimikoF13, F: FredM11

Focus Group 2 (FG2)

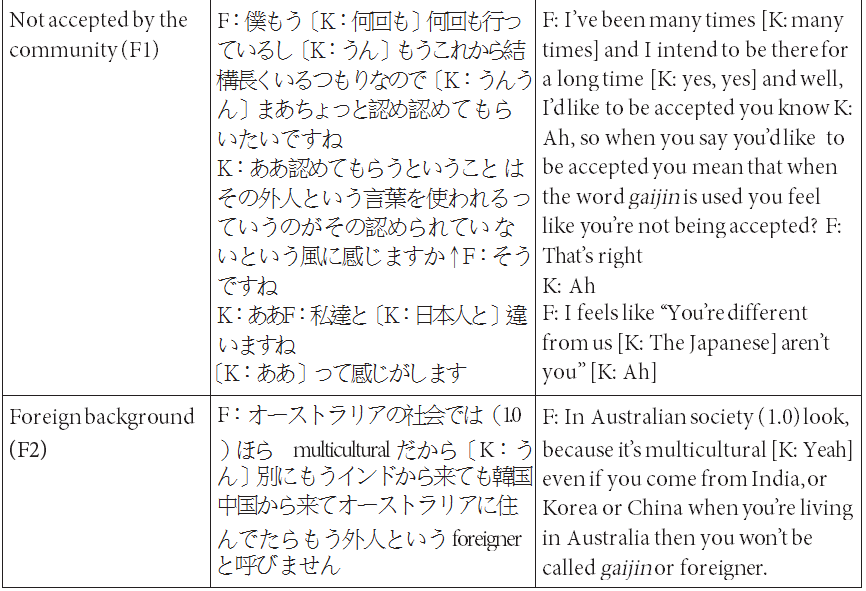

Three interpretations of the word gaijin were identified in the discourse of FG2 participants. The first interpretation identified by the participants related to physical appearance (E&T1). When asked whether he had ever been called a gaijin in circumstances similar to those in Film1, TomM10 claimed that he had not, because he was Asian in appearance. Following Film 2, EijiM16 claimed that he thought the depiction of the physical characteristics of the foreigner in the film (tall, blue eyes) was ”typical” of a gaijin. This supports the finding that there are particular physical characteristics that are associated with referents of the word gaijin.

The second interpretation identified was non-verbal behaviour (E1). This interpretation was identified after TomM10 related that he had been referred to ”jokingly” as a gaijin by friends in Japan when he had difficulty using chopsticks. EijiM16 supported this claim by noting that even when a person spoke fluent Japanese that he was able to discern whether they were Japanese or not based on their body language, and that the term gaijin is used to refer to ”those with a difference in culture”. This demonstrates that the characteristics referenced by the word gaijin are ultimately more complex than the more easily identified physical and linguistic characteristics. EijiM16 responded at length in his FUI about the difficulty foreigners faced in adapting to Japanese cultural practices and norms, and argued that foreigners could be identified easily by deviations from native participants’ behavioural norms, regardless of linguistic ability. EijiM16 revealed that his use of the word gaijin in FG2 to refer to this distinction between Japanese and non-Japanese occurred involuntarily, suggesting that the word gaijin was deeply associated with non-verbal behaviours that are considered different to what is accepted to be the Japanese norm.

The third interpretation identified was the use of English, which was congruent with interpretation K1 identified in FG1. This finding indicates that the word gaijin indexes difference on multiple levels, based on observation of linguistic ability, non- verbal behaviour and physical appearance.

Table 5 summarises the interpretations of the word gaijin shared by the participants of FG2.

Table 5 – Interpretations of gaijin identified by EijiM16 and TomM10

E: EijiM16, T: TomM10

Focus Group 3

The interpretation of gaijin as indexing physical difference (C1) was identified by CharlotteF12 who claimed that the word gaijin was not used of her because of her Asian experience. However, CharlotteF12’s understanding of the word gaijin differs in that it was based not on particular physical characteristics, but rather on a perception that the purpose of the word gaijin was to differentiate between races. CharlotteF12 claimed in the focus group that negative perceptions associated with the word gaijin were based on poor translation and misrepresentation, and explained in her FUI that differentiating between races was a positive thing, as it is natural for ”people to put things into categories”. SatomiF9 agreed in her FUI that the word gaijin was used in such a manner, but that she did not consider such use of the word to be discriminatory. SatomiF9 added that the word was used to indicate a person who was non-Japanese.

SatomiF9 made few original contributions as to any physical characteristics associated with referents of the word gaijin, and indicated in both the focus groups and FUI that she did not particularly like the word gaijin, and that she had not had much experience in interacting with NNSJ. SatomiF9 maintained a blank expression for much of the focus group and nodded constantly, and did not stop the tape in the FUI once of her own accord. SatomiF9’s verbal and non-verbal behaviour was interpreted by the researcher as passively listening, indicating little or no previous exposure to discourse related to the use of the word gaijin. The above suggests that SatomiF9 did not share the interpretation of the word gaijin as referring to particular physical characteristics such as whiteness, due to a lack of exposure to discourse with either NSJ or NNSJ regarding the use of the word gaijin or the characteristics associated with its referents.

The second interpretation identified in FG3 resembled interpretation F2 from FG1. In not associating the word gaijin with particular linguistic or physical characteristics, SatomiF9 interpreted the word gaijin as indexing foreignness’ (S1), which she defined as having been brought up in a different environment. This interpretation of the word gaijin displays strong similarities to the ideal’ interpretation of the word expressed by FredM11 in FG1. SatomiF9 related that the meaning of the word changed based on the place and situation, echoing the sentiment expressed by FredM11 in his FUI. SatomiF9 further applied this logic to claim that in Sydney, she considered herself to be a gaijin. Thus SatomiF9’s interpretation of gaijin differs from those raised by KimikoF13 and in FG2, in which the word gaijin is anchored as deictically opposite to Japanese.

Table 6 summarises the interpretations of the word gaijin shared by the participants of FG3.

Table 6 – Interpretations of gaijin identified by CharlotteF12 and Satomi F9

C: CharlotteF12, S: SatomiF9

Use of the word gaijin by the Japanese speech community in Sydney

While the above discussion details the broad interpretations of the word gaijin by the Japanese speech community, it is necessary for the purposes of this study to frame the use of these interpretations by the speech community in Sydney. Of the three focus groups, the first and third identified uses of the word gaijin by the Japanese speech community in Sydney.

In FG1, FredM11 purposefully informs the focus group of his observations of the use of the word in Sydney, stating that ”in Australia the Japanese people are gaijin“. Furthermore, the word is inadvertently used by KimikoF13 in a Sydney context, describing non-Japanese restaurant staff. In FG3, as detailed above, SatomiF9 states that she considers herself to be a gaijin in the Sydney context. These observations were further confirmed in the respective FUIs.

In contrast, FG2 did not identify any usage of the word gaijin in the Sydney context. Conversely, the participants of FG2 stated that using this word would be situationally inappropriate given the multicultural nature of Sydney, reflecting in particular EijiM16’s high contact situation fluency.

Discussion

Following the above description of the data we can establish that there are multiple interpretations of the word gaijin, which can be grouped into two models of gaijin: the portable notion of the Absolute gaijin, and the contextually specific Relative gaijin.32 These models of the word gaijin function as indices that point to and define individuals or groups of people that are considered to be different to the speaker. As eleven interpretations of the word gaijin were identified, it became clear that the word is used by certain NSJs and NNSJs to point to referents that possess defining characteristics. Thus, the referents indexed by the word gaijin are dependent on the interpretations of the speaker, per the Absolute or Relative model of gaijin as defined below.

The role of indexing in the understanding of Japanese social order was highlighted in the volume edited by Bachnik and Quinn.33 Bachnik encouraged a shift in the conceptualisation of Japanese society from semantic to pragmatic meaning, realised in an understanding of indexing, rather than fixed structural principles.34 While Bachnik advanced this reasoning with a focus on a collective Japanese concept of self-embodied in the terms uchi and soto, this discussion borrows the concept of indexing as a means of mapping and identifying one’s own position and identity, by both verbal and non-verbal means. This approach dictates a focus on deixis in investigating the way in which individuals conceptualise themselves and the world around them.35 The above approach has been criticised by Hasegawa and Hirose,36 who have questioned the linguistic evidence for the uchi and soto concept towards which Bachnik and Quinn’s volume was aimed, citing examples of speech in which the Japanese self could not be conceived as collective, such as personal thoughts and mental states. Although this paper accepts that there are a number of definitions of self in a Japanese context, it makes use of the concept of indexing as a useful conceptual tool in determining the function that the word gaijin plays within the Japanese speech community in Sydney.

Bachnik defines an index as a scale or axis along which relationships can be gauged against a located reference point. Such indexing can be realised through any kind of communication: Bachnik provides honorifics, bowing (non-verbal behaviour as a means of communication) and choice of topic as examples.37 For the purposes of this discussion, the speaker is defined as the located reference point, and the referent of the word gaijin is defined as the deictic opposite. While the notion of an index infers several degrees along a scale between the speaker and the referent gaijin, this study produced insufficient evidence to determine whether different terms such as the variant gaijin-san or the alternative gaikoku-jin represent different degrees on the same scale.

The Absolute gaijin

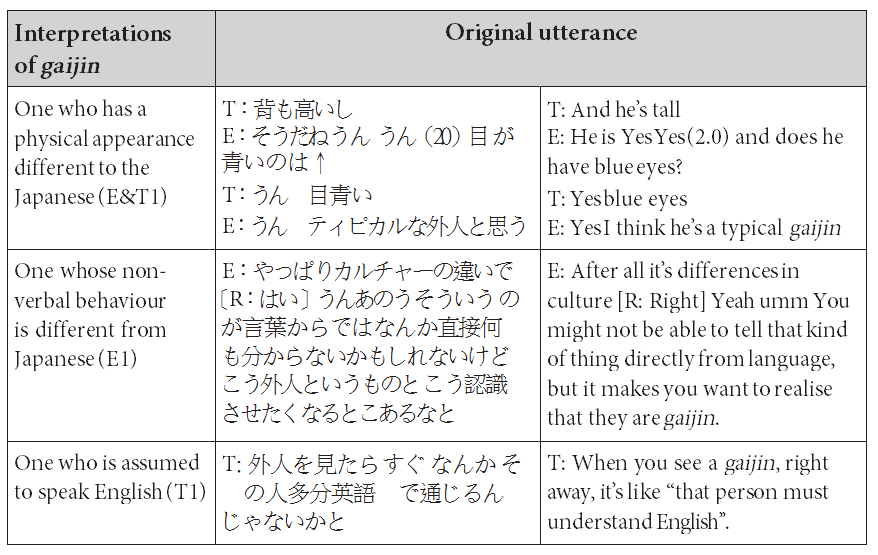

The Absolute gaijin model represents the specific physical and linguistic interpretations of gaijin that are broadly identified in the preceding literature, and that were expressed by participants in each of the focus groups. This model of gaijin is defined here as absolute’ because the referents of the model are unchanging, regardless of the location of the user of the word and the referent. In Figure 1 below, this is represented by the cline pointing away from the speaker. The Absolute gaijin is assumed to be the most common model.

FG1 demonstrated that such indexing may be interpreted as estrangement from the speaker by NNSJ referred to as gaijin. This is also represented by the cline on Figure 1 below, however it is placed in square brackets as it is an interpretation of the index by the referent. The focus groups did not produce any evidence that such estrangement is a conscious function of the word gaijin, however this is not discounted by the findings given above.

The Absolute gaijin as an index of difference offers some insight into the way its users map their relationships and interactions with those NNSJ that correspond to the characteristics associated with the word gaijin. Indexing referents with the word gaijin categorises the referents as being different, and therefore asserts the identity of the speaker as Japanese. This notion of the use of the word gaijin is perhaps rooted in the assumption of Japanese homogeneity that continues to be relatively prevalent in Japanese society.38 Parallels can be drawn to the use of the word gaijin by the NSJ radio interviewer to assert his Japanese identity in Nishizaka’s study of a NSJ-NNSJ interaction.39 The assertion of identity of Japanese descendent Brazilians with the use of the word is another example of such usage.40 Thus the use of the Absolute gaijin model is part of the way in which NSJ may present their Japanese identity when participating in an interaction with a NNSJ, or a discourse referring to an NNSJ.

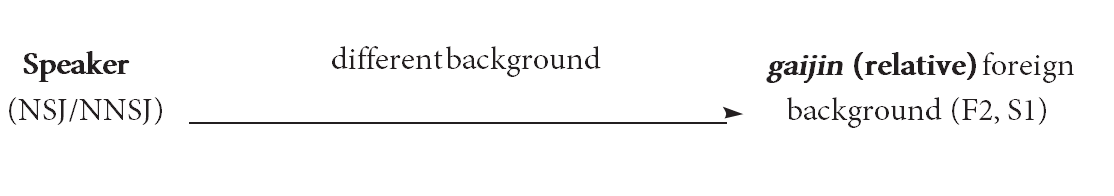

Figure 1 — The Absolute gaijin as an index

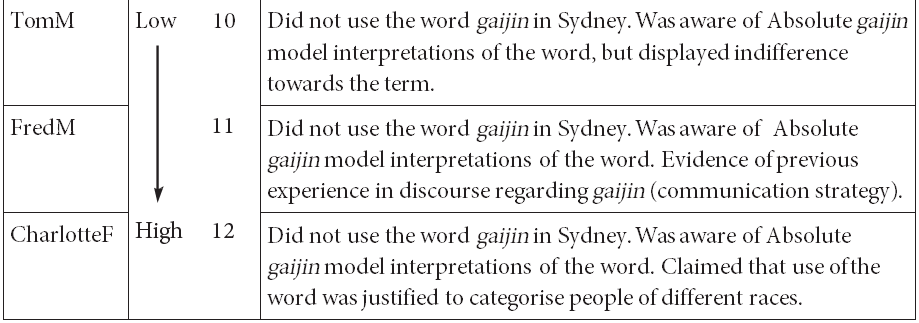

The Relative gaijin

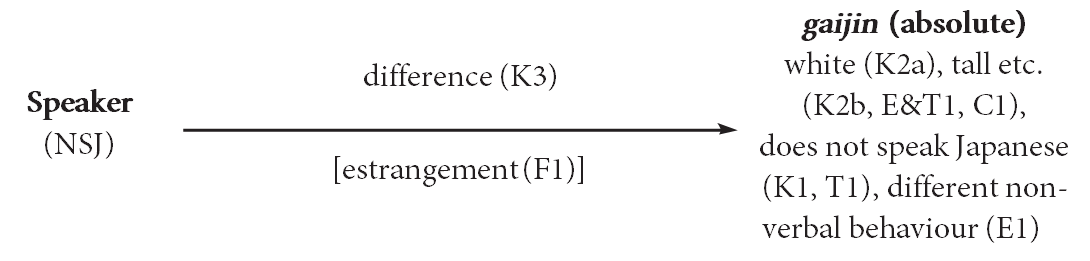

The Relative gaijin model differs from the Absolute gaijin model in that its referent is not clearly defined as possessing particular characteristics, and as such, both the speaker and the gaijin are variables. The model is relative’ because the referent of the word gaijin changes relative to the identity of the speaker. This model can be distinguished from the Absolute model of gaijin, where an ethnically Japanese NSJ can be referred to as gaijin, whereas such a reference is unthinkable in the prevalent Absolute model of gaijin. The Relative gaijin model indexes difference as defined by the referent possessing a different background to the speaker (F2, S1). This is represented by the cline in Figure 2 below.

In this model, both the speaker and the referent could be any combination of NSJ and NNSJ. Where the referent of the Absolute model of gaijin is anchored to a particular set of interpretations, which are juxtaposed to the speaker, the Relative gaijin is more simply a deictic term for a referent with a background different to that of the speaker.

The Relative gaijin model can be compared to the Absolute model in terms of the use of the word to categorise the referent as being different to the speaker. However, the notion of the use of the word gaijin to assert the Japanese identity of the speaker does not apply to the Relative gaijin model.

Figure 2 — The Relative gaijin as an index

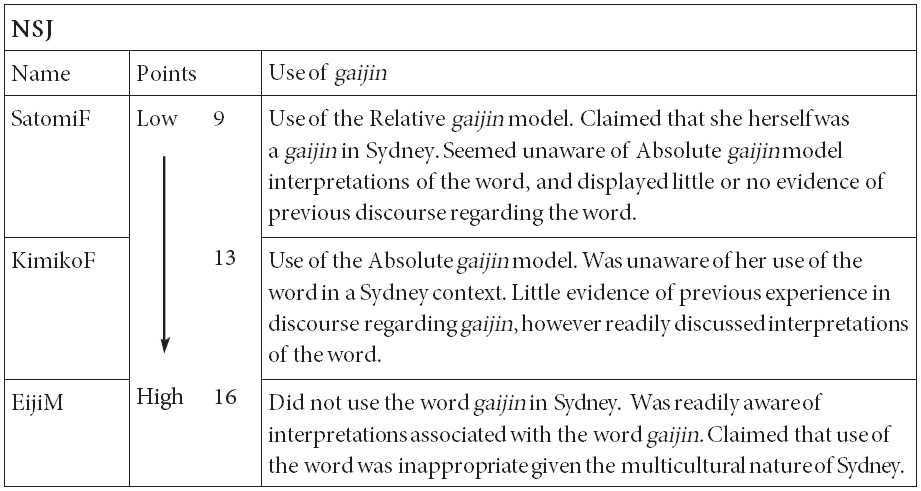

Contact situation fluency and the use of the word gaijin

As discussed above, participants were allocated points to determine the level of experience of NSJ and NNSJ in interacting with NNSJ and NSJ members of the Japanese speech community respectively (contact situation fluency), in order to consider the effect of such experience upon the use of the word gaijin by research participants. This was based upon an expectation by the researcher that a higher level of contact situation fluency would reduce the likelihood of the participant’s use of the word gaijin. This expectation was challenged by the use of the word gaijin by SatomiF9, with the lowest point score of all of the participants. This suggests that certain individual experiences may play a large role in influencing the use of the word gaijin by particular individuals. However, a relationship was identified between the contact situation fluency of the NSJ participants and their exposure to previous discourse regarding the word gaijin, which was reflected in their participation in the focus groups. Table 7 demonstrates the relationship between the use of the word gaijin and the participant’s contact situation fluency, as the participants are placed in order of their points from low to high.

Table 7 — Contact situation fluency and the use of the word gaijin in Sydney

When ordered by their contact situation fluency, the NSJ participants exhibit increasing levels of awareness of interpretations of the word gaijin, as developed by prior experience of discourse with NNSJ. SatomiF9 displayed little or no evidence of previous discourse regarding the word gaijin, and her use of the Relative model of gaijin suggests a lack of awareness of the prevalent Absolute gaijin model. With higher exposure to related discourse, KimikoF13 was readily aware of the interpretations of the word gaijin. However, EijiM16, with the highest level of exposure to NNSJ, demonstrated both an awareness of the interpretations of the word gaijin, and an understanding that the use of the word was not considered appropriate given the multicultural context that the speech community is situated in. Although there is insufficient evidence to identify a trend, the above suggests that increased exposure to discourse with and regarding NNSJ influences the likelihood that the word gaijin would be used to refer to an NNSJ in contexts outside of Japan. This limited sample also suggests that a progression exists in the evolution of the usage of the word gaijin between the two models from the Relative model, to the Absolute model, and finally to not using the word at all, although a progression from Absolute to Relative could be equally likely.

None of the NNSJ participants claimed to use the word in Sydney. The NNSJ participants were closely grouped in contact situation fluency points, and a relationship between the points and awareness of the interpretations of the word gaijin was not identified. While TomM10 and CharlotteF12 displayed a similar level of awareness of interpretations of the Absolute gaijin model, FredM11 exhibited the most in-depth understanding of these interpretations. FredM11 not only displayed knowledge of the Relative and Absolute gaijin models, but also expressed an understanding of the inappropriateness of the word in the multicultural context of Sydney. As the participants are closely grouped in points, it is likely that the individual experience of participants is involved. While TomM10 and CharlotteF12 are Asian in appearance and have few experiences of being referred to as gaijin, FredM11 identifies with many of the characteristics associated with the prevalent Absolute model of gaijin, and as such, has increased exposure to the use of the word, and discourse regarding the word.

Conclusion

The definition of the two models of gaijin highlights a complexity that exists in the usage of the word that has not been explored by the literature reviewed earlier in the article. While the interpretations of the word gaijin defined within the Absolute model of gaijin have been apparent for some time, the Relative gaijin model introduces a novel aspect of the word that reflects a different and significant way of conceiving the relationship of NSJ and NNSJ outside of the established paradigm.

By uncovering the interpretations of the word gaijin in the Japanese speech community in Sydney, it was discovered that the word functions as an index of the difference of the referent from the user of the word. The word was identified as an index of difference, indexed differently in each model. The Absolute gaijin model was found to index referents with particular characteristics, and it was proposed that such indexing achieved the secondary function of asserting the Japanese identity of the NSJ speaker. In contrast, in the Relative gaijin model the referent of the word changed contextually according to the identity and location of the speaker. In this model, the word gaijin functioned as a demonstrative term for a person with a different background to the community that the speaker represents.

The approach of the study confirmed the prevalent interpretations of the word in the preceding literature, and uncovered a new model of its use. A similar methodology could be applied to other terms within and outside of Japan, such as gaikoku-jin, imin (immigrant’) and nikkei-jin (a person of Japanese ancestry’), to empirically confirm common interpretations of the word, and to search for new and different models of their use. The influence of contact situation fluency on such interpretations could be considered in these cases.

References

Bachnik, J. M., Introduction: uchi/soto: Challenging Our Conceptualizations of Self, Social Order, and Language’ in Bachnik, J. M. and Quinn, C. J. (eds.), Situated Meaning (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), pp. 3-37. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv8pzcdw.8.

Bryman, A., Social Research Methods (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Fan, S. C., Taishōsha no naisei wo chōsa suru: Forōappu Intabyū [Investigating the self reflection of research participants: The Follow-Up Interview]’ in Neustupnà½, J. V. and Miyazaki, S. (eds.), Gengo Kenkyū no Hōhō [Methods of language research], (Tokyo: Kuroshio Publishing, 2002), pp. 87-96.

Fasold, R. W., The sociolinguistics of language (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1990).

Figueroa, E., Sociolinguistic Metatheory (Oxford: Elsevier Science, 1994).

Gottlieb, N., Language and Society in Japan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511614248.

Gottlieb, N., Linguistic Stereotyping and Minority Groups in Japan (London: Routledge, 2006). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203099216.

Gumperz, J. J., Types of Linguistic Communities’, Anthropological Linguistics, vol. 4, no. 1 (1962), pp. 28-40.

Hammersly, M., Questioning Qualitative Inquiry (London: Sage Publications, 2008). https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857024565.

Hasegawa, Y. and Hirose, Y., What the Japanese language tells us about the alleged Japanese relational self ‘, Australian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 25, no. 2 (2005), pp. 219-251,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07268600500233019

Hill, J. H., Styling locally, styling globally: What does it mean?’, Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 3, no. 4 (1999), pp. 542-556,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9481.00095

Hirose, Y. and Hasegawa, Y., Nihongo kara mita Nihon-jin – Nihon-jin ha ”Shūdan shugi-teki” ka [Japanese people viewed from the Japanese language – Are the Japanese ”collectivists”?]’, Gekkan Gengo, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 86-97, no. 2, pp. 86-96 (2001).

Hirose, Y. and Hasegawa, Y., Deikushisu no chūshin wo nasu Nihon-teki Jiko [The Japanese self as the centre of deixis]’, Gekkan Gengo (February 2007).

Huddleston, J. N., Gaijin Kaisha: Running a foreign business in Japan (New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1990).

Hymes, D., Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1974).

IELTS, Getting my results’. Retrieved 6th June 2009, from http://www.ielts.org/test_takers_information/getting_my_results.aspx.

Ishii, S., The Japanese welcome-nonwelcome ambivalence syndrome toward Marebito/Ijin/Gaijin strangers: Its implications for intercultural communication research’, Japan Review, vol. 13 (2001), pp. 145-170.

Kotani, M., Reinforced codes and boundaries: Japanese speakers’ remedial episode avoidance in problematic situations with “Americans”‘, Research on Language and Social Interaction, vol. 41, no. 4 (2008), pp. 339-363,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08351810802467761

Lo, A., Codeswitching, speech community membership, and the construction of ethnic identity’, Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 3, no. 4 (1999), pp. 461-479,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9481.00091

Masumi-So, H., Kaigai no Nihon-go shiyō no Ibunka Sesshoku Bamen ni okeru Sōgo-kōi Bunseki — Nihon-jin Sanka-sha to Ōsutoraria-jin Sanka-sha no Bamen no Sesshoku-do [Analysis of Interaction in Japanese-speaking Contact Situations Overseas – ”Contacted-ness” of Situations involving Native-speaker Japanese and (Japanese-speaking) Australians]’, in Proceedings of the 28th Congress of Intercultural Education Society, Tokyo, Japan (June 2-3, 2007), pp. 174-175.

Michiura, T., Terebi hōsō yōgo no genzai [Television Broadcast Language at present]’ in Sanada, S. and Shoji, H. (eds.), nihon to tagengo shakai [Japan and Multilingual Society] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shinsho, 2005).

Muraoka, H., Forōappu Intabyū ni okeru shitsumon to ōtō [Questions and replies that occur in Follow-Up Interviews]’ in Muraoka, H. (ed.), Sesshoku Bamen no Gengo Kanri Kenkyū [Language Management Research in Contact Situations], vol. 3, no. 104 (2004), pp. 209-226.

Neustupnà½, J.V., Nihongo kenkyū no hōhō: dēta shūshū no dankai [Methods of Japanese studies: At the level of data collection]’, Taikensan ronsō, vol. 28 (1994), pp. 1-24.

Nishizaka, A., Doing interpreting within interaction: The interactive accomplishment of a “Henna Gaijin” or “Strange Foreigner”‘, Human Studies, vol. 22 (1999), pp. 235-251,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1005492518477

Saville-Troike, M., The ethnography of communication: An introduction (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2003),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470758373

Silverman, D., Analyzing Talk and Text’ in Denzin, N. K. and Lincoln, Y. S. (eds.), Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials (California: Sage Publications, 2003), pp. 340-362.

Sugimoto, Y., An introduction to Japanese society (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2003).

Tsuda, T., Strangers in the ethnic homeland: Japanese Brazilian return migration in transnational perspective (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003). https://doi.org/10.7312/tsud12838.

Valentine, J., Pots and pans: identification of queer Japanese in terms of discrimination’ in Livia, A. and Hall, K. (eds.), Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender and Sexuality (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 93-114.

Daniel Curtis

University of New South Wales

- The term gaijin was commonly used in English sources in reference to foreign workers and companies in Japan in the 1980s and 1990s, see for example Huddleston, Gaijin Kaisha. ↩

- Clavell, Gai-Jin. ↩

- Gottlieb, Linguistic Stereotyping and Minority Groups in Japan, p. 14; Michiura, Terebi hōsō yōgo no genzai (Television Broadcast Language at present)’. ↩

- Burakumin: the descendants of the lower echelons of the Japanese feudal Gottlieb, Language and Society in Japan. ↩

- Gottlieb, Linguistic Stereotyping and Minority Groups in Japan, p. 97. To the best of the author’s knowledge there is no more recent survey of foreign resident attitudes towards the word gaijin. ↩

- Hymes, Foundations in Sociolinguistics, p. 57. ↩

- Ibid., p. 64. ↩

- Ibid., p. 55. ↩

- Ibid; Fasold, The sociolinguistics of language; Saville-Troike, The ethnography of communication: an introduction, pp. 108-11; Figueroa, Sociolinguistic Metatheory. ↩

- Ishii, op. cit. ↩

- Marebito: rare stranger’, Ijin: Archaic term for a foreigner’ or for a person from outside one’s Ibid., p. 151. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 241-6. ↩

- Gottlieb, Language and Society in Japan; Gottlieb, Linguistic Stereotyping and Minority Groups in Japan. ↩

- Gottlieb, Language and Society in Japan, pp. 117-8; Gottlieb, Linguistic Stereotyping and Minority Groups in Japan, pp. 96-7. ↩

- Gottlieb, Language and Society in Japan, p. 117. ↩

- Ibid, p. 118. ↩

- Tsuda, Strangers in the ethnic homeland, p. 372. ↩

- Second or later generation descendants of Japanese settlers. ↩

- Figueroa, Sociolinguistic Metatheory. ↩

- Lo, op. cit.; Kotani, op. cit. ↩

- See Silverman, Analyzing Talk and Text’, pp. 343-5; Hammersley, Questioning Qualitative Inquiry, pp. 89-98. ↩

- IELTS, Getting my results’. ↩

- Derived from a points system used in Masumi-So, Kaigai no Nihon-go shiyō no Ibunka Sesshoku Bamen ni okeru Sōgo-kōi Bunseki’, pp. 174-175. ↩

- Bryman, Social Research Methods, pp. 475-6. ↩

- For example, KimikoF13 = Kimiko, Female, 13 Participant names are presented in this way to ensure that relevant information is contained in a single code. ↩

- Film 1: Azumanga Daioh: the Animation’, Unknown episode, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kn2ogbiOuk&NR=1; Film 2: Azumanga Daioh: the Animation’, Unknown episode, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTm2tk1yzSI; Film 3: Outside World News #2 – GAIJIN BANNED’, http://www.youtube. com/watch?v=Dvm9X-aafWM&NR=1. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Fan, Taishōsha no naisei wo chōsa suru: Forōappu Intabyū‘, pp. 88-90. ↩

- Muraoka, Forōappu Intabyū ni okeru shitsumon to ōtō‘, p. 210. ↩

- Neustupný, op. cit., pp. 15-17; Fan, op. cit., pp. 93-4. ↩

- Gottlieb, op. cit.; Ishii, op. cit.; Nishizaka, op. cit. ↩

- The models may be glossed in Japanese as 絶対的な外人 (zettai teki na gaijin) and 相対的な外人 (sōtai teki na gaijin). ↩

- Bachnik and Quinn, Situated Meaning. ↩

- Bachnik, Introduction’, pp. 12-20. ↩

- Ibid, pp. 12-23. ↩

- Hasegawa and Hirose, What the Japanese language tells us about the alleged Japanese relational self ‘; Hirose and Hasegawa, Nihongo kara mita Nihon-jin‘; Hirose and Hasegawa, Deikushisu no chūshin wo nasu Nihon-teki jiko‘. ↩

- Bachnik, op. cit., pp. 24-6. ↩

- Sugimoto, An introduction to Japanese society. ↩

- Nishizaka, op. cit., p. 246. ↩

- Tsuga, op. cit., p. 372. ↩