Teaching culture in the Japanese language classroom: A NSW case study

Published December, 2009

Pages 104-125

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21159/nv.03.06

New Voices

Volume 3

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2009

Permalinks for references are available in the HTML version of this article.

Abstract

This study examines, through a qualitative case study approach, how non-native- speaking (NNS) Japanese language teachers in New South Wales (NSW) teach culture and why. The study seeks to understand the pedagogy used to teach culture, teachers’ attitudes and beliefs on teaching culture and how these attitudes and beliefs have been influenced by past experiences. This study also explores how the NSW K-10 Japanese syllabus and concepts of Intercultural Language Learning (IcLL) are being implemented in teachers’ classrooms.

Two non-native-speaking (NNS) Japanese language teachers from a selective secondary school in NSW were interviewed and their classes observed over three days. Analysis of interview and observation data shows that these teachers teach culture as determined by language content, integrate language and culture teaching and teach culture as observable and factual. The study shows that both teachers view culture teaching as easier than language teaching, however their views on the influence of the syllabus differ. The study explores the teachers’ past experiences and how these affect how they feel towards, and teach culture. Finally, this study looks at how the teachers’ practices reflect concepts of IcLL such as integrating language and culture, student-centred learning and how their status as NNS teachers affects their culture teaching.

Introduction

It is becoming widely acknowledged that communicative competence is not the only goal of language learning. Culture is inseparable from language and it is only through an intercultural approach to language teaching and learning that effective communication and intercultural understanding can occur. Inquiry into Intercultural Language Learning (IcLL) began around a decade ago and is entering mainstream approaches to languages education. One of the key messages from a recent Australian national seminar on languages education was to encourage an intercultural approach.1 Although research exists on how IcLL has been integrated within curriculum frameworks,2 there has been little attention paid to how culture is currently being taught in the classroom and whether it reflects the goals of IcLL. This study hopes to shed some light on this area by asking how Japanese language teachers in one case study school teach culture and why. The study involved interviewing and observing the classes of two non-native-speaking (NNS) teachers of stages 4 and 5 Japanese at a Sydney secondary school.

The theoretical orientation of the study is the intersection of the areas of teacher cognition, language and culture teaching and NNS teachers. Teacher cognition refers to the unobservable cognitive dimension of teaching — what teachers know, believe and think’.3 The field of teacher cognition recognises that teachers’ behaviour is governed by decision-making influenced by their knowledge, thoughts, beliefs, teaching context and past experiences.4 It should be noted, however, that this study relates to teacher cognition as a teacher’s thoughts, beliefs and knowledge rather than cognition as it is referred to in educational psychology.5 The second of these theoretical orientations is language and culture teaching, concepts which will be explored in detail in the literature review.

The third of these theoretical orientations relates to NNS teachers. NNS teachers are generally defined as not possessing the characteristics of native speaking (NS) teachers which, although not universally agreed upon, include acquisition of the language during childhood, intuitions about grammar, wide-ranging communicative competence and the ability to write creatively in the language.6 Whereas the differences in language proficiency between NS teachers and NNS teachers are contested, in a sociolinguistic sense NS teachers are associated with confidence and authority over the target language. The merits of NNS teachers and how they can contribute to IcLL are considered further in the next section.

Literature review

Intercultural language learning is the biggest change in language teachers’ practice since the 1980s … offering the chance to deepen the learning experience by encouraging social interaction, making connections with other learning areas and supporting self-reflection.’

Lia Tedesco

Australian Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations7

The main premise of IcLL is that language and culture are inseparable. It is impossible to communicate in a language without understanding the cultural connotations of its use. Likewise, it is impossible to understand a different culture without learning how different ideas and ways of seeing the world are expressed through its language. As foreign languages are not just a code version of English,’8 culture is not just another component to be tacked onto the end of the code — it is embedded within it.9

Kramsch says that every time we speak, we perform a cultural act.10 When we speak the words we use reflect our identity and the cultural context we are in. We choose certain words to express politeness however the degree of politeness necessary in different situations comes down to culture. For example, learning the grammatical differences between plain, polite and honorific form in Japanese and trying to use them according to Australian norms cannot lead to successful communication.11

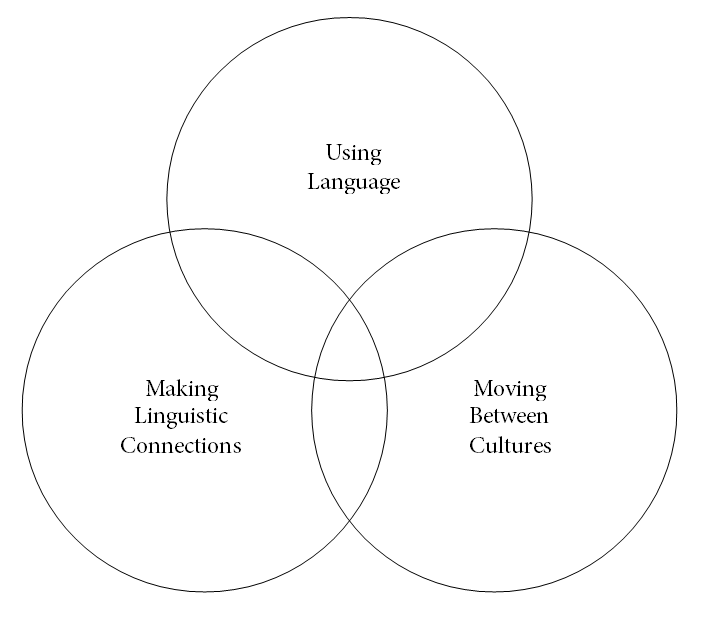

Unlike communicative language learning that uses a model of native speaker dialogue, the model for IcLL is communication between native and non – native speakers.12 This allows for recognition that the students’ native culture and language will affect their communicative needs and resources.13 IcLL aims to take a constructivist approach by valuing a student’s native language and culture and starting language study from that point.14 Therefore in IcLL, mimicking native speakers is no longer the goal of language learning.15 In an interesting turn, this also means that practices that are less native-like can be seen as progress in IcLL, as the student has obviously reflected on their own culture and negotiated a third place’ for themselves.16 The third place is a negotiation between ones native culture and the target culture and is represented in the NSW languages syllabus through the objective moving between cultures’.17 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The three objectives outlined in the NSW K-10 Japanese Syllabus.18

In reviewing literature for the study, both traditional culture teaching approaches and IcLL approaches were investigated. One traditional approach to teaching culture is avoiding cultural content in lessons due to students’ low language proficiency or only teaching culture for the exact same reason.19 Saving culture lessons for late afternoons or the end of term because they are perceived as being easier to teach than language-based lessons is another traditional approach to culture teaching.20 In contrast to these traditional approaches, intercultural approaches assert that language and culture should be taught in an integrated manner21 and that culture lessons should be intellectually stimulating.22 This study was also informed by literature examining the intersection of IcLL with other areas such as the role of resources, intercultural skills and NNS teachers.

It is common for teachers to use cultural content from textbooks, which is usually derived from the communicative topic being studied at the time such as ordering food or travelling.23 Galloway outlines the following common approaches to teaching culture:

- The Frankenstein approach a taco from here…a bullfight from there’;

- The 4 F approach (folk dances, festivals, fairs and food);

- The tour guide approach (geography);

- The by-the-way’ approach when teachers share anecdotes or offer bits of information to illustrate a point.24

In communicative textbooks, cultural content can usually be defined as static culture (that which does not change and can be learnt as facts) and does not reflect the needs of a user of the language.25 For example, information on the speed of trains in Japan might accompany an exercise on how to buy a train ticket. This approach to culture as an add-on’ may be practical in a communicative sense, however it does not always give rise to a very stimulating educational experience’ as topics and issues are dealt with on a superficial level.26

IcLL skills are represented by Moran’s Cultural Knowings Framework which refers to four knowings’: Knowing About, Knowing How, Knowing Why and Knowing Oneself. Knowing About’ refers to knowing facts about products, practices and perspectives of the culture. Knowing How’ relates to acquiring cultural practices — knowing how to act in the culture. Knowing Why’ requires an understanding of the cultural perspectives — perceptions, values and attitudes. Finally Knowing Oneself’ means acknowledging one’s own values, perspectives and feelings.27 Teachers can give their students opportunities to use these skills by relinquishing their role as the provider of facts’. Rather than giving out information, teachers can plan activities for students to investigate and find answers’ to cultural questions28 and act as mediators between their students and the target culture.29

The concept of mediation between cultures is related to the merits of NNS teachers, who are thought to be more adaptable to the inconsistencies of language and culture. NNS teachers approach these areas with a unique multilingual perspective,’ — a privilege that even native speakers do not have access to.30 Some would believe, however, that a native speaker represents the culture automatically whereas NNS teachers must try much harder and it is perhaps this extra effort required that make NNS teachers valuable for IcLL.31 As they have learnt both the target language and culture from scratch, they can serve as good role models for their students.32 They have had to learn about the target culture explicitly unlike native speakers, and also may have had to reflect on their own culture to negotiate a third place’ in which to operate.33

Research design and methodology

The research questions developed for the study were:

- How do NNS Japanese language teachers teach culture in the case study school?;

- What are their attitudes toward and beliefs on teaching culture and how have they been influenced by their past experiences?;

- How do their teaching practices and thoughts on teaching culture reflect the concepts of Intercultural Language Learning?

The study focused on two teachers in a particular school. A case study was chosen in order to provide a holistic description of language learning … within a specific population and setting’.34 Although generalisations about how Japanese teachers teach culture and why cannot be made from this small study, it contributes to the field by providing insights into the complexities of two teachers’ experiences within the same context and serves to highlight different influences on a teacher’s thoughts and behaviour.35

The study utilised two data collection measures. Teachers were interviewed to find out their views on teaching culture and how their beliefs and practices are influenced by prior experiences and several of the teachers’ classes were observed to look for evidence of culture teaching. The sample — two NNS Japanese language teachers teaching stages four and five at a Sydney secondary school — choice was a combination of convenience and purpose:36 convenience because the researcher taught there for four weeks on practicum and the teachers were willing to participate; and purposive as the school was co-educational and thus eliminated any opportunity for bias within culture teaching arising from teaching groups of all boys or all girls. The school was also suitable for this case study as there were two NNS Japanese language teachers on staff with significantly different backgrounds and teaching experience. Only NNS Japanese teachers were involved because the depth required to compare experiences and beliefs of NS and NNS was beyond the scope of this study.

The case school is a selective co-educational secondary school in suburban Sydney. The majority of students at the school are from Asian backgrounds and this majority is even more pronounced in Japanese classes. Jane37 teaches Years 8 and 9 and, less frequently, Year 10 and 11 classes. She is employed three days a week, one of which is designated to English as a Second Language (ESL). Arthur works full time and is also Head Teacher of Administration. He takes a Year 7 class for a taster course of French, German, Japanese and Latin once a week, Years 10 and 11 the majority of the time and all Year 12 classes.

Data collection procedures included document analysis, interviews, observation and personal communication. The LOTE, languages other than English: strategic plan consultation document38 and the NSW K-10 Japanese syllabus39 were analysed for references to directives for teaching cultural content.

Interviewing was chosen as a data collection procedure in order to elicit how a teacher feels about culture teaching, how they assess their approach, their classroom practice and their motivations for teaching the way they do. Interviews give teachers the opportunity to express approaches to culture teaching that may not be observable and give information about how their past experiences have affected their culture teaching.40

Interviews were semi-structured in format and conducted over two days in June 2007. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed. Interview questions were designed to assess teachers’ beliefs about teaching culture, their past and present interactions with Japanese culture, their feelings about their ability to teach culture and their non-native speaker status and their opinions on policies and professional development relating to culture teaching.

Observation of classes allowed the researcher to witness how teaching plans are implemented and how students respond to culture teaching. Multiple observations were undertaken to develop a more multilayered understanding of the participants and their context’.41 The observations were semi-structured in that they were planned and previously established categories were used, however the categories were broad and allowed the researcher to include field notes.42 Observations were not audio or video recorded. A total of nine lessons were observed over the same two days the interviews were conducted.

Class observation coding sheets based on a category system were developed to record instances of culture teaching in the classroom.43 Categories were developed according to themes explored in the literature review, such as teacher-centred culture teaching, student-centred culture teaching and integrated language and culture teaching. The data analysed for the literature review enabled the researcher to recognise relevant instances of behaviour and note them down.44 Further clarification on interview and observation data was obtained through personal communication via email with the participating teachers.

Two data collection measures were used in order to result in the same research findings through triangulation. The combination of interviews that assess self-reported behaviour and observations that assess actual behaviour results in triangulation.45 By collecting data through two means, the researcher’s bias is reduced, a richer case study can be created46 and the study’s validity is increased, as one method can further explore findings not accessible through the other.47

A pilot interview and class observation with a NNS Japanese teacher not involved with the study was also carried out to uncover any problems with the proposed procedures.48 As well as some interview questions, the classroom observation instrument was modified after the pilot observation. Specific categories such as those referring to tasks, activities, anecdotes and reflection in the earlier version were modified to become the broader categories of:

- Culture being generated by the teacher;

- Culture being elicited by the teacher;

3. Culture being generated by the students;

4. Language and culture integration.

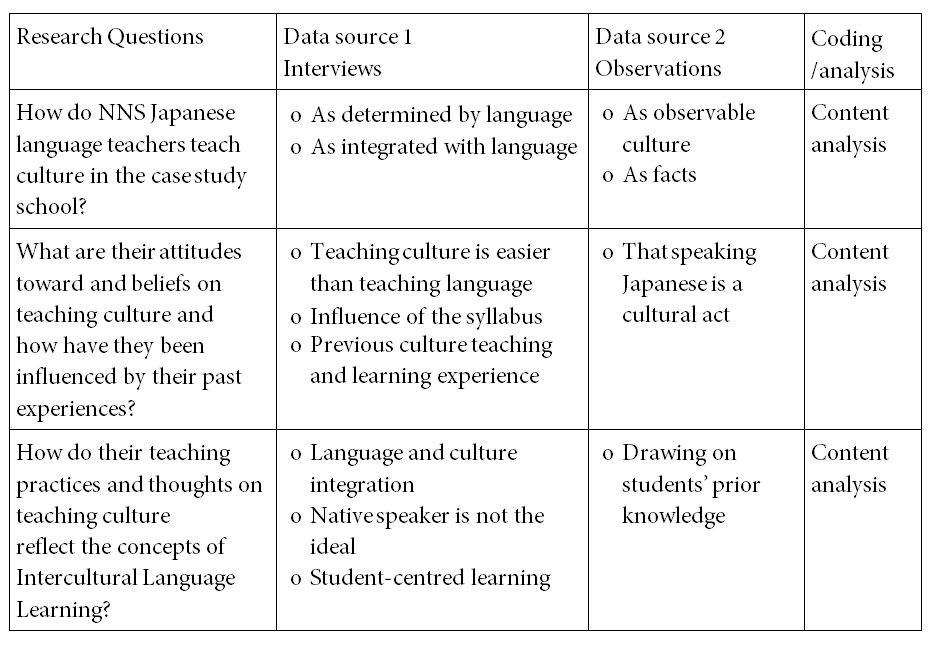

Interview data, observation data and personal correspondence were analysed in accordance with data gathered during the literature review, the NSW K-10 Japanese syllabus and NSW strategic plan for languages released in 1992 in order to explore the research questions. Findings were then collated into the following table to assist in answering the research questions.

Table three: Research questions, data sources and analysis

Findings and discussion

Demographic information

Jane’s first year of teaching Japanese was in 2007, although she had been teaching ESL in schools since 2001. Jane and her family immigrated to Queensland when she was a child and her family spoke English and Cantonese at home.49 She studied Japanese at high school and Japanese and Chinese at university. She lived in Japan and taught English for three years and also taught English in China for 2 months at the end of her teaching degree. Arthur has been teaching languages (French and Latin) since 1980 and Japanese since 1981. He describes the place where he grew up as a conservative Caucasian community in rural New South Wales. At university he studied to be a French and Latin teacher and began studying Japanese because it was a requirement of his course. Arthur has not lived in Japan but has travelled there nine times, accompanying students on six of those trips.

Culture teaching in the classroom

When speaking to both teachers about their culture teaching practice it was discovered that, to a large extent, the language content being covered in class determines how the teacher decides what to teach as cultural content. Arthur described how cultural content was chosen depending on whether it was related to the language under study: If you teach family you teach about Japanese families, if you’re teaching transport you teach about Japanese transport.’ Jane stated that the language and culture under study in the textbook guided her culture teaching: We cover topics in the modules, in the textbook. I sort of fit it in around that, almost like the language dictates the culture.’ While Arthur seemed to accept this way of structuring culture content around the communicative function, Jane seemed somewhat disappointed that culture was not playing a more central role in her lessons. This issue reflects Scarino’s research that says cultural content in textbooks is derived from the language topic of study and is treated as an add-on’ to the main educational objective — developing communicative skills.50

In IcLL the main educational objective is what you want the students to understand about the target culture, and the language content necessary to meet that objective is then devised. In this case study, language and culture are connected by the teacher setting a communicative goal, setting language structures to be covered and then adding-on’ the cultural content. Integrating language and culture teaching refers to combining language and cultural content in the same lesson and designing the outcomes according to cultural goals as well as language goals. Jane demonstrated her beliefs about how language and culture are integrated when explaining how she incorporated Japanese culture in her lessons:

Right from the very beginning we begin with what I expect in class and especially I guess things like standing up when the teacher comes in and bowing, greeting at the beginning of the lesson and also at the end of the lesson.

We discuss Japanese writing and things that I guess are borrowed from Chinese culture or Korean culture.

Jane’s comments on how the students should use greetings in class reflect that she sees the Japanese words as being embedded with contextual meaning and wants her students to experiment with performing a cultural act when they come to class.51 Her comment on Japanese writing as also having a cultural origin shows that she considers both spoken and written communication as having a cultural context. Arthur reported that he believed language and culture teaching should be integrated and so was undertaking the Intercultural Language Teaching and Learning in Practice (ILTLP)52 project to extend his knowledge in the area.

A theme that arose during classroom observations was that culture was taught as a visible, tangible entity. During a lesson watching a Japanese animated film, Jane often elicited cultural information from students based on what they could see, such as the film’s setting. Students also related to this visual approach by making comments about what they saw such as noticing the characters sleeping on futon on the floor.

Teaching culture as something that is observable can harness two of what Moran termed cultural knowings.53 By watching a film, students are knowing about’ products of culture such as a futon and practices such as sleeping on the floor and are also knowing how’ Japanese people act in certain situations.54 Although Arthur did not use visual stimulus in any of the lessons observed during the limited observation period, he referred to things the students had seen in previous lessons or on trips to Japan such as paper cranes at Hiroshima’s Atomic Dome and Asakusa’s famous red lantern.

Both teachers demonstrated that they think of culture as having a factual basis. The concept of background knowledge’ was often present, for example when Jane gave her students information on the director of the film they were watching and his motivation for making it. Arthur also referred to facts when asking students what Okinawa was famous for. While the answer he was expecting (tourism) did not come from the students, their responses were diverse. The students made reference to seafood, American military bases and tanned people in manga which suggests their background knowledge of Japanese culture extends from history to geography to popular culture. This highlights the idea that even facts are not static culture and are subjective.55 Resources and even teacher anecdotes are subjective and can become part of the hidden curriculum'(cultural values indirectly communicated through content choices).56

Culture teaching — attitudes, beliefs and past experiences

During interviews both teachers alluded to the idea that culture lessons are easier than language lessons for both teachers and students. Jane said:

It feels like it’s easier to teach culture… after writing reports and doing assessments and what not I guess it’s a little bit easier to prepare those sorts of lessons. Also you can show media as well, show movies… in a way that is teaching culture by them just watching… I suppose you do save it up for these times when you do have time to relax and the students have time to relax.

This statement can be seen as reflecting both Jane’s status as a beginning teacher as well as her experiences learning about Japanese culture. As Jane acquired most of her cultural knowledge while living in Japan, it is natural that she uses her familiarity with culture to create lessons for her students when she is feeling overworked. The fact that she acquired her knowledge through immersion in the culture is also evident in her opinion that the students will learn about Japanese culture by passively observing what is depicted in films. Reflecting the viewpoint of the students, Arthur said:

You can talk from your own personal experiences as you’re going along. It’s nice to add little anecdotes… and some students have actually said that they really enjoyed the little stories and anecdotes as they were studying Japanese after they’d left because they said it was nice to break up the lesson with something like that.

Arthur’s comment reflects the idea that culture can be added to lessons using the by-the-way’ approach57 and that students appreciate this as a welcome break from studying language, which is more intellectually demanding.58 It also suggests that students appreciate the personal dimension anecdotes give and that they are curious to hear about their teacher’s experiences in and knowledge of Japan.

Both teachers viewed the influence of the syllabus on their culture teaching differently. Arthur commented that teaching gifted and talented students, who usually get through the required syllabus content quite quickly, allowed for freedom within the syllabus and other policies:

There are certain policies that you have to fulfil… and sometimes you can actually fulfil those policies by use of the cultural side of things. But there’s a big push of course to integrate the culture these days and if you’re actually sort of making use of some policy to satisfy a requirement that’s almost like taking the cultural aspect out and doing it as a separate entity, which is now going against the flow. It should all be part and parcel of the one approach.

Arthur’s participation in the teacher professional development project, the ILTLP, is also evident here as he recognises that using cultural content to satisfy policy requirements goes against the principles of IcLL to a certain extent.59 Jane, on the other hand, sees the syllabus as a hindrance to her ability to teach culture:

Maybe it’s just because I’m beginning and I’m finding it difficult to do everything I need to do and also make it interesting for students. I just feel that culture and language are so connected that it’s necessary to have a lot of culture so it does make sense for the students and…[they] take more of an interest.

It is interesting to note that the K-10 syllabus specifies very little in terms of specific language content to be covered. It is perhaps, therefore, more the textbooks Jane and Arthur use than the syllabus that restrict their freedom to teach culture and determine the language they teach. The strongest influence on a teacher’s implementation of IcLL, however, is not curriculum frameworks but their own values and attitudes that are in turn influenced by their past experiences.60

Arthur discussed his experiences of language and culture being taught separately. When he was learning languages at high school, one lesson per week was set aside as a culture lesson’ and this approach was also encouraged when he was completing teacher training at university. There was no integration between language and culture, to the extent that students had a separate culture book to bring along for their culture lesson and could leave their grammar book at home:

I remember running off reams and reams of cultural notes to discuss with the students and you’d hand out seven or eight pages just because you’d have to introduce the culture and discuss the culture and everything else with the students on that particular day…It was just ridiculous because you were doing things that really didn’t relate to what you were teaching in the grammatical lessons just because you had to fill up your culture lesson.

Arthur’s belief that language and culture teaching should be integrated is a reaction against the way he was taught at school and university. In her interview, Jane also reflected on learning calligraphy and looking at pictures of kimono and temples in high school Japanese classes, however her experiences in Japan have had a far greater impact on how she views the teaching and learning of culture: It’s just an idea when you’re studying it in the classroom and it’s not this real thing… Well obviously when you’re there in Japan it hits you. Wow. It hits you in the face.’ She also said that she wanted to discuss Japanese popular culture with the students and try to use authentic materials to engage them. Finding authentic materials that were at a level appropriate for both the students’ language proficiency and age proved difficult, however, reflecting the challenge of modifying resources yet keeping them authentic and motivating for students.61

Jane sees speaking Japanese as automatically engaging with the culture due to her past experiences living in Japan. An example of this is giving classroom greetings and instructions in Japanese and having the students stand and bow to the teacher before the class starts. Jane also uses the word prints’ for the photocopied handouts she gives the students and this comes from the Japanese word for such items (albeit derived from English) purinto’. She says that this is something she picked up in Japan and consciously decided to use in her lessons.62 As well as Kramsch’s concept of speaking as a cultural act,63 Jane’s classroom also demonstrates aspects of the third place.64 Through using Japanese language and customs in the classroom, Jane’s students are experimenting with a third place and also moving between cultures’ as the NSW syllabus directs. Arthur encourages students to think about their own third place by discussing with them their own knowledge of Japan and experiences there. When discussing some class work referring to the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto, which some of the students had visited, he questioned the use of the word kirei (pretty) to describe it, suggesting to the students that a Japanese person would be more passionate in their description because they would feel proud of it.

Teachers’ thoughts, practice and IcLL

During her interview, Jane often expressed sentiments that she wished to integrate language and culture learning more in her lessons:

I feel like often in class I’ll just go in and say ok this is the topic and this is the language we’re learning today’ and you know here’s the vocab’ and this is how we put these sentences together’ and I think … they’re just words you know. And if you do pre-teach culture and teach the students ok we use this in this situation’ I think they’d definitely be a lot more motivated to learn the language and also be more interested in learning about Japanese culture. They might learn the language because of that.

Although Jane was not familiar with IcLL and had not received any professional development in the area, her experiences living in Japan mean she is aware of the underlying concepts of IcLL and tries to incorporate them in her teaching. She also recognises the potential for cultural content to contextualise language learning, spark interest and motivate students.65

Arthur supported integrating language and culture because he viewed it as a holistic and balanced way of teaching. He saw integration as a good way to cater for students who were keen to focus on language content: They’ve come to learn to speak and to read and to be more confident in the language … increasing the amount of culture they’re doing is not perhaps going to help them in that so that’s why if it’s integrated it’s much better.’ One of the points that arose in the literature review was the idea that native speaking practices are not always the ideal in IcLL. Since the literature on NNS teachers focuses on language rather than culture teaching, comments Arthur made on the differences are very interesting:

Well a native speaker, I’ve always felt, tends to teach the culture because they’ve lived the culture but I don’t know whether sometimes the amount of culture or the appropriateness of it might apply… I tend to pick and choose and wait to see what the reaction is with the students as to whether they are interested in this particular thing or not.

This quote suggests that, as a NS teacher, Arthur feels somewhat privileged when teaching culture as, since he does not have any personal connection with the culture, he can look at cultural content objectively and choose aspects that are most appropriate for his students. This relates to the privilege Kramsch talks about in non-native speakers having a unique multilingual perspective’ and suggests that maybe NNS teachers also have a unique multicultural perspective’.66

Arthur also describes how a NS teacher’s personal connection with the target culture may affect their willingness to teach aspects of culture that they see as problematic: I know some of them are horrified to teach anything that’s modern or new thinking because it might be looked upon as if it’s their thinking and so they won’t teach it.’ The idea of teaching controversial aspects of culture supports Byram’s maxim to get past the superficial and stereotypical aspects of culture by challenging everything and further suggests the ability of NNS teachers to successfully teach interculturally.67 While this is only one teacher’s opinion on the differences between his own and NS teachers’ ways of teaching culture, it raised some interesting issues. Jane’s perspective on being a NNS teacher was that she did not see any difference between her ability to teach culture and that of a NS teacher except that a NS teacher may have more access to resources. Whereas other Australian studies on NNS language teachers found they felt insecure due to their language proficiency,68 the teachers interviewed for this study do not feel they have any disadvantage when teaching culture. If anything, Arthur’s comments show that he feels his ability to teach culture is enhanced because he is removed from the culture unlike a native-speaker. Jane and Arthur’s positive attitudes toward teaching culture also reflect Medgyes’ idea that NNS teachers can serve as good role models for their students.69

Arthur believed his students had significant background knowledge of Japan and were able to find answers to cultural questions for themselves. In his interview, Arthur spoke about his aim to make cultural content student-centred:

The students’ interest in music and anime, I tend to leave to them because I know that they’ll go on the internet and find those things… I’m not an expert in that field. But some of them really are expert in that field and perhaps it’s actually something they could share with the rest of the class.

I think it’s important to know the clientele a little bit better… what are their interests, what do they know, what comparisons can they make between their own culture and that of the Japanese and their experience of living in Australia.

Jane also mentioned the student’s interests in her interview: I’m often asked questions about popular music or you know, popular culture that teenagers are interested in and I have no idea about that anymore.’ It is interesting to compare Jane and Arthur’s responses while considering that Arthur is undertaking professional development in IcLL and Jane is not. Arthur feels that he can surrender his role as the provider of facts’70 and let his students develop their intercultural skills by investigating things for themselves. Jane, however, feels as though it is her responsibility to gather facts and knowledge her students may be interested in.

Both Jane and Arthur were drawing on students’ prior knowledge when teaching Japanese culture. Before students watched the animated film, Jane asked them what they thought Japan was like, to which they replied anime, advanced technology, mountains, cherry blossoms, shopping and food. The film being shown was set in rural Japan in the 1950s which gave the students a different perspective to the ones they were familiar with and Jane asked them to think about their impressions of Japan while they watched. Arthur prompted students for information about places in Japan they had been to or learnt about and also had them reflect on their own background. When he compared the town of Hahndorf in South Australia (which featured in a reading passage) to Old Sydney Town the students could instantly relate to the context. By using a film that contrasted with students’ perceptions of Japan, Jane was introducing them to a variety of perspectives to achieve IcLL.71 Arthur encouraged students to use their own background and past experiences to better understand something new, thus utilising Moran’s concept of Knowing Oneself72 and the skills of comparing and reflecting.73 Jane and Arthur also both demonstrated the IcLL concept of valuing a student’s background and prior knowledge.74

Conclusion

This case study has shed light on how two NNS teachers from different backgrounds teach culture in their classrooms. The two teachers are similar in the following ways:

- Both currently teach culture content that is determined by the language content being covered at the time;

- Both teachers expressed that they thought language and culture teaching should be integrated;

- Both teachers see culture as being both observable and factual to a certain extent and thus teach using films and anecdotes to engage and inform

Jane and Arthur teach culture differently because:

- Jane creates a third place through using Japanese language and customs in the classroom;

- Arthur creates a third place by encouraging students to reflect on their own background and experiment with Japanese

Jane and Arthur share the belief that culture is easier for teachers to teach and for students to learn. Despite having different backgrounds, both teachers’ attitudes towards teaching culture were influenced by their past experiences:

- Arthur was determined to move away from his own experiences of learning and teaching culture as a separate subject to language;

- Jane was keen for students to experience Japanese culture in an authentic way, as she herself experienced it by living in

Jane and Arthur also saw culture teaching differently in terms of the syllabus.

- Arthur was confident the requirements could be covered while allowing time for other things;

- Jane felt, as a beginning teacher, somewhat stifled by the syllabus.

With regards to teaching practices and thoughts on teaching culture, the two teachers differ because:

- Jane has undergone no professional development in IcLL while Arthur has;

- Arthur’s ILTLP project training has encouraged him to allow the students more input into the curriculum whereas Jane feels she must broaden her own knowledge in order to appeal to the students’

However their thoughts on teaching culture both reflect concepts of IcLL because they:

- do not feel they have a disadvantage when teaching culture due to their non-native speaker status;

- agree with the IcLL concept of making learning more student-centred.

Implications

This case study of two Japanese teachers in a NSW secondary school has raised issues that many teachers will be able to relate to. It has shown how two different teachers teach culture in their classrooms and other teachers can use this information to reflect on their own practice. It has also explored some of the reasons why Jane and Arthur teach the way they do which highlights the role of a teacher’s thoughts, attitudes, knowledge and past experiences in shaping their practice. The study also highlights instances of IcLL in Jane and Arthur’s classrooms which will help teachers to identify and implement such practices in their own lessons.

This study also has implications for policy makers as it shows how two teachers are interpreting and implementing the NSW K-10 Japanese syllabus and especially the objective of moving between cultures’. It also profiles two teachers from NSW and shows their attitudes and beliefs on teaching culture as well as how their past experiences have influenced their teaching. Policy makers can take note of these attitudes, beliefs and past experiences and reflect on how pre-teacher education and professional development opportunities can assist teachers in implementing the syllabus objectives successfully. This study can also show policy makers how teachers are currently implementing IcLL in their classrooms.

Further research and concluding thoughts

As the teachers participating in this study were both working at an academically selective school, researching the experiences of teachers working at other schools could contribute to this field of study. Investigating the experiences of teachers who have completed the ILTLP to discover how they have implemented IcLL and their opinions on its success in the classroom would also be revealing.

Further research could incorporate the reflections of students on the cultural content in their Japanese lessons and determine whether culture teaching in classrooms contributes to students’ intercultural competence. A broader study including NS teachers could shed light on the effect of teachers’ language and cultural backgrounds on their culture teaching practices. In the same vein, a study including teachers from a wide range of schools could determine the effect of students’ backgrounds, school culture and curriculum demands on culture teaching.

Australia’s capacity to participate in global spheres such as politics and economics is often associated with its ability to cultivate foreign language skills amongst its citizens. The ability of Australians to interact successfully in various language and cultural contexts, especially within the Asia-Pacific region, is a current concern of many and it is for this reason that further research on IcLL and its implementation in schools is necessary. As Japan continues to be a strong diplomatic and economic partner of Australia, the teaching of Japanese continues to thrive in Australian schools. In order for this relationship to continue, the teaching of Japanese must be regularly analysed and updated to reflect the needs of both countries.

This case study has shed light on how two NNS Japanese language teachers in NSW teach culture and why. They teach culture that is integrated with language and determined by language, that is observable and factual. They are trying to make culture learning more student-centred and help their students develop intercultural skills. They teach culture because it is a break from language teaching and is mandated by the syllabus, but mainly because they believe it is a vital and valuable facet of language learning.

References

Armour, W. S., Becoming a Japanese language learner, user, and teacher: Revelations from life history research’, Journal of Language Identity and Education , vol. 3, no. 2, (2004), pp. 101-125,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327701jlie0302_2

Board of Studies, Japanese K-10 Syllabus (Sydney: 2003).

Borg, S., Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe and do’, Language Teaching ,vol. 36, no. 2, (2003), pp. 81-109,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444803001903

Byram, M., Commentary’, Kokusai kenkyū shōkai kotoba, bunka, shakai no gengo kyōiku’ (International conference language, culture, society’s language education’) (Tokyo: Waseda University, September 17-18, 2005).

Byram, M., & Alred, G., Becoming an intercultural mediator: a longitudinal study of residence abroad’, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, vol. 23, no. 5, (2002), pp. 339-352,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01434630208666473

Byram, M., & Doyé, P., Intercultural competence and foreign language learning in the primary school’, in Frost, D., and Driscoll, P. (eds.), The teaching of modern foreign languages in the primary school (London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 138-151.

Crandall, J., Language Teacher Education’, Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, vol. 20, (2000), pp. 34-55,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0267190500200032

Corbett, J., An intercultural approach to English language teaching (Clevedon, England, Buffalo, New York: Multilingual Matters, 2003).

Department of Education Science and Training, Maximising the opportunity. A report on the national seminar for languages education (2006, October 30-31). Retrieved 31 May 2007, from www.asiaeducation.edu.au/public_html/reports.htm.

Jane, Personal Communication (2007, August 8).

Jane, Personal Communication (2007, September 10).

Kaikkonen, P., Intercultural learning through foreign language education’, in Kohonen, V., (ed.), Experiential learning in foreign language education (Harlow, New York: Longman, 2001), pp. 61-105.

Kellehear, A., The unobtrusive researcher – a guide to research methods (St Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1993).

Kohler, M., Framing culture: How culture’ is represented in Australian state and territory language curriculum frameworks’, Babel, vol. 40, no. 1, (2005), pp. 12-17.

Kramsch, C., Culture and language teaching’, in Brown, K., (ed.), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics (2nd ed.) (Boston: Elsevier, 2006),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00611-8

Kramsch, C., The privilege of the nonnative speaker’, in Blythe, C., (ed.), The sociolinguistics of foreign-language classrooms: Contributions of the native, the near-native and the non-native speaker (Boston: Heinle, 2003), pp. 251-262.

Liddicoat, A., Intercultural language teaching: principles for practice’, The New Zealand Language Teacher, vol. 30, (2004), pp. 17-23.

Liddicoat, A., Static and dynamic views of culture and intercultural language acquisition.’, Babel, vol. 36, no. 3, (2002), pp. 4-11.

Liddicoat, A., & Crozet, C., (eds.), Teaching languages, teaching cultures (Melbourne: Language Australia, 2000).

Liddicoat, A., Lo Bianco, J., & Crozet, C. (eds.), Striving for the Third Place: Intercultural competence through language education (Melbourne: Language Australia, 1999).

Liddicoat, A., Papademetre, L., Scarino, A., & Kohler, M., Report on intercultural language learning (Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training, 2003).

Lo Bianco, J., New times, world kids, third place’, Kokusai kenkyū shōkai kotoba, bunka, shakai no gengo kyōiku’ (International conference language, culture, society’s language education’) (Tokyo: Waseda University, September 17-18, 2005).

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M., Second language research: Methodology and design (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2005).

McDonough, J., & McDonough, S., Research methods for English language teachers (New York: Arnold, 1997).

Medgyes, P., Native or non-native: Who’s worth more?’, ELT Journal, vol. 46, no. 4, (1992), pp. 340-349,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/46.4.340

Moran, P. R., Teaching culture: Perspectives in practice (Australia, Boston: Heinle & Heinle, 2001).

New South Wales Department of School Education, LOTE, languages other than English: Strategic plan consultation document (Sydney: The Department, 1992).

Nunan, D., Research methods in language learning (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Paige, R. M., Jorstad, H., Siaya, L., Klein, F., & Colby, J., Culture learning in language education: A review of the literature (Minneapolis: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition Minnesota Univ., 2000).

Phillips, E., IC? I see! Developing learners’ intercultural competence’, LOTE CED Communique, vol. 3, (2001), pp. 1-8.

Samimy, K., & Kurihara, Y., Nonnative speaker teachers’, in Brown, K. (ed.), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics (2nd ed.) (Boston: Elsevier, 2006),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00614-3

Scarino, A., The neglected goals of language learning’, Babel, vol 34, no. 3, (2000), pp. 4-11.

Sercu, L., The foreign language and intercultural competence teacher: The acquisition of a new professional identity’, Intercultural Education, vol. 17, no. 1, (2006), pp. 55-72,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14675980500502321

Sercu, L., Garcia, M. D., & Prieto, P. C., Culture learning from a constructivist perspective: An investigation of Spanish foreign language teachers’ views’, Language and Education, vol. 19, no. 6, (2005), pp. 483-495,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500780508668699

Tudor, I., The dynamics of the language classroom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Caroline Mahoney

University of Sydney

Caroline Mahoney graduated from the University of Technology, Sydney, in 2005 with a combined degree in Journalism and Japanese. In 2008 she was awarded First Class Honours in her Master of Teaching at the University of Sydney. She is currently studying Japanese language education at Waseda University, Tokyo, and working towards her PhD.

- Department of Education Science and Training, Maximising the opportunity’, p. 4. ↩

- Kohler, Framing culture’. ↩

- Borg, Teacher cognition in language teaching’, p. 81. ↩

- Ibid., p. 81. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Davies cited in Samimy & Kurihara, Nonnative speaker teachers’, pp. 679-680. ↩

- Department of Education Science and Training, op. cit., p. 15. ↩

- Ibid., p. 8. ↩

- Liddicoat et al., Striving for the third place’, p. 182. ↩

- Kramsch cited in Liddicoat & Crozet, Teaching languages, teaching cultures’, p. 2. ↩

- Liddicoat, Intercultural language teaching’, p. 18. ↩

- Crozet & Liddicoat, The challenge of intercultural language teaching’, p. 113; Liddicoat, Static and dynamic views of culture’, p. 11. ↩

- Liddicoat et al., Report on intercultural language learning’, p. 46. ↩

- Corbett, An intercultural approach to English language teaching’, 28; Liddicoat et al., Striving for the third place’, p. 185. ↩

- Corbett, op. cit., p. 40. ↩

- Kramsch cited in Liddicoat, Static and dynamic views of culture’, p. 9. ↩

- Board of Studies, Japanese K-10 syllabus’, p. 14. ↩

- Board of Studies, Japanese K-10 syllabus’, p. 14. ↩

- Liddicoat, op. cit., p. 9; Byram et al. cited in Paige et al., op. cit., p. 37. ↩

- Kaikkonen, Intercultural learning through foreign language education’, p. 61. ↩

- Liddicoat, op. cit., p. 9; Liddicoat & Crozet, Teaching languages, teaching cultures’, p. 14; Liddicoat, Intercultural language teaching’, p. 18. ↩

- Byram, Commentary’, p. 230; Kohler, op. cit., p. 17; Kramsch cited in Paige et al., op. cit., p. 43. ↩

- Scarino, The neglected goals of language learning’, p. 8. ↩

- Galloway cited in Phillips, IC? I see! Developing learners’ intercultural competence’, p. 1. ↩

- Liddicoat, Static and dynamic views of culture’, p. 7. ↩

- Clarke cited in Scarino, op. cit., p. 9. ↩

- Moran, Teaching culture: Perspectives in practice’. ↩

- Phillips, op. cit., p. 4. ↩

- Byram & Alred, Becoming an intercultural mediator: a longitudinal study of residence abroad’, p. 348. ↩

- Kramsch, The privilege of the nonnative speaker’. ↩

- Medgyes, Native or non-native: Who’s worth more?’, p. 369. ↩

- Ibid, p. 346; Crandall (2000, p. 43) says that NNS have the advantage of coming from the same linguistic and cultural background of their students. This is true for many TESOL situations however would not apply to an ethnically diverse area such as Sydney, where this study was conducted. ↩

- Liddicoat, op. cit., p. 9. ↩

- Mackey & Gass, Second language research’, p. 171. ↩

- Ibid., p. 172. ↩

- Ibid., p. 122. ↩

- Pseudonyms for both teachers chosen by researcher. ↩

- New South Wales Department of School Education, LOTE’. ↩

- Board of Studies, op. cit. ↩

- Mackey & Gass, op. cit., p. 173. ↩

- Ibid., p. 176. ↩

- McDonough & McDonough, Research methods for English language teachers’, p. 105. ↩

- Nunan, Research methods in language learning’, p. 97. ↩

- McDonough & McDonough, op. cit., p. 105. ↩

- Kellehear, The unobtrusive researcher’, p. 5. ↩

- Mackey & Gass, cit., p. 181. ↩

- Kellehear, op. cit., p. 10. ↩

- Mackey & Gass, op. cit., p. 43. ↩

- Jane, Personal Communication, August 8. ↩

- Scarino, op. cit., p. 8. ↩

- Kramsch cited in Liddicoat, Intercultural language teaching: principles for practice’, p. 18. ↩

- The ILTLP was a professional development project for language teachers funded by the Federal Government’s Department of Education, Science and Training. ↩

- Moran, op. cit. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Liddicoat, Static and dynamic views of culture’, p. 7; Stodolosky and Grossman cited in Paige et al., p. 33. ↩

- Liddicoat et al., Report on intercultural language learning’, p. 52; Cunningsworth cited in Tudor, op. cit., p. 73. ↩

- Galloway cited in Phillips, op. cit., p. 1. ↩

- Kaikkonen, op. cit., p. 61. ↩

- Cross-curriculum Content, intended to achieve broad learning outcomes, is specified in the Japanese K-10 syllabus through incorporating objectives such as Information and Communication Technologies, Civics and Citizenship and Difference and Diversity. ↩

- Liddicoat, et al., op. cit., p. 43; Sercu et al., op. cit., p. 484. ↩

- Liddicoat, et al., op. cit., p. 67. ↩

- Jane, Personal Communication, September 10. ↩

- Kramsch cited in Liddicoat and Crozet, Teaching languages, teaching cultures’, p. 2. ↩

- Kramsch cited in Liddicoat, Static and dynamic views of culture’, p. 9. ↩

- Byram cited in Corbett, op. cit., p. 25; Paige et al., op. cit., p. 30; Tudor, op. cit., p. 72. ↩

- Kramsch, The privilege of the nonnative speaker’, p. 252. ↩

- Byram, Commentary’, p. 330. ↩

- Armour, Becoming a Japanese language learner, user and teacher’, pp. 114-116. ↩

- Medgyes, op. cit., p. 346. ↩

- Phillips, op. cit., p. 4. ↩

- Byram & Doyé, op. cit., p. 149. ↩

- Moran, op. cit. ↩

- Liddicoat et al., Report on intercultural language learning’, p. 46. ↩

- Corbett, op. cit., p. 28; Liddicoat et al., Striving for the third place’, p. 185. ↩