Japanese wives in Japanese-Australian intermarriages

Published December, 2009

Pages 64-85

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21159/nv.03.04

New Voices

Volume 3

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2009

Permalinks for references are available in the HTML version of this article.

Abstract

The diasporic experiences of Japanese partners married to Australians and living in Australia are largely unexamined. This article is based on a study, conducted for an honours thesis, which invited four Japanese wives living in South East Queensland to describe, together with their Australian husbands, their family’s interactions with Japan, its language and culture, and the local Japanese community. It was recognised that the extensive social networks these wives had established and maintained with local Japanese women from other Japanese-Australian intermarriage families were an important part of their migrant experience.

This article will firstly review the literature on contemporary Japanese- Australian intermarriage in Australia and Japanese lifestyle migration to Australia. It will then describe and examine the involvement and motivations of the four wives in their social networks. Entry into motherhood was found to be the impetus for developing and participating in informal, autonomous networks. Additionally, regular visits to Japan were focused on engagement with existing family and friendship networks. The contemporary experience of intermarriage for these women is decidedly transnational and fundamentally different from that of the war brides, or sensō hanayome.

Introduction

Research into Japanese residents, migrants and families in Australia, as well as their local ethnic communities, has slowly accumulated over the last 20 years. The lives, histories, and contributions of Japanese have been examined by historical works and celebrated in various commemorative publications which have explored the relationship between Australia and Japan.1 These studies have also been generated as part of celebrations of Queensland’s multiculturalism and diverse ethnic communities.2

An early investigation of the Japanese community in Brisbane focused on the integration of Japanese residents into Australian society.3 Fieldwork that is more recent has thrown light on the emergence of deterritorialised urban ethnic communities developing around autonomous and non-organisational social networks.4 Similar observations have been made by other studies conducted in Sydney and Melbourne.5 While sojourning corporate families have been a feature of Japanese communities in Australia from the 1960s through to the mid-1990s, their proportion has dropped considerably due to an increase in other migrant types.6 Satō refers to them as lifestyle migrants’,7 and Nagatomo draws upon this concept to understand Japanese migration to Australia as a form of transnational leisure.8 The diasporic experiences and identity negotiations of Japanese residents is another aspect which has been researched, albeit to a limited degree.9

There remain few gendered perspectives on the migration of Japanese to Australia. One example is Nagata’s re-examination of prostitutes in the prewar Japanese diaspora.10 However, while postwar migrants have been predominantly female there has been an absence of rigorous discussion about gender and its role in their migration experiences. The scope of the original study upon which this article is based was not ambitious enough to correct this. However, the work has attempted to provide a starting point for a more thorough examination of gender in Japanese migration to Australia by identifying, in particular, the role of motherhood in the development of and participation in informal, autonomous networks with other Japanese mothers of similar migrant backgrounds.

This article will firstly review the literature on contemporary Japanese- Australian intermarriage in Australia and Japanese lifestyle migration to Australia. Next, the methodology of my original study will be outlined. Finally, the involvement and motivation of Japanese wives who have established and maintained extensive social networks with local Japanese from other Japanese-Australian intermarriage families in South East Queensland will be described and examined.

Contemporary Japanese-Australian Intermarriage in Australia

Researchers have used a variety of terms to refer to the marriage of people from different backgrounds, including cross-cultural marriage and interracial marriage.11 The translated form of the Japanese term kokusai kekkon, or international marriage’, is also used.12 Each of these foregrounds one particular aspect of difference: culture, race, and nationality respectively. Penny and Khoo use intermarriage, explaining that its definition depends on the perceptions about what is different within the society in which the marriage takes place’13 and may involve religion, birthplace, and socioeconomic status, in addition to the previous three. While considering such differences where they occur, their Australian study of migration and integration focuses on the intermarriage of individuals born and raised in Australia and their partners who were born and raised in other countries. My study followed this usage.

A typology of Japanese residents in Australia separates intermarriage couples into two generational groups.14 The first are the war brides of the 1950s who married Australian servicemen stationed in Japan during the Allied occupation after the Pacific War. The second are the contemporary marriages of mainly younger women in their 30s and 40s. This work is concerned with the second generational group and will not undertake a thorough comparative analysis. However, it is important to note briefly at this point that interviews with war brides have revealed that many experienced loneliness and alienation, with little opportunity to associate with other Japanese, speak Japanese or obtain Japanese foodstuffs. With many coming to regard Australia as their home and choosing to become citizens, yet still proudly maintaining their ethnic origins, Nagata describes them as having a hyphenated cultural identity: Japanese-Australians.15

It is difficult to obtain a clear picture of contemporary Japanese-Australian intermarriage through official statistics. The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates the population of Japan-born residents for 2007 at 45,613,16 however no detailed data which may indicate how many are married to Australian citizens appears to have been kept. The report of the then Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs entitled The People of Australia’, contains the most useful and recent data available.17 Using figures from the 2001 Census, it shows that 6,232 people born in Australia responded that Japan was the birthplace of one or both of their parents. Of those, 620 had an Australian mother and Japanese father, and 1,955 had a Japanese mother with an Australian father. However, these figures do not account for couples who have no children, whose children were born overseas, or how many are still dependants of their parents.

Reflected in these figures is the gender imbalance of Japanese migrants to Australia. Both Australian and Japanese government figures agree that approximately 63% of Japanese migrants are women.18 This is attributed to the migration of Japanese women who have married Australian men.19 In Mizukami’s Melbourne study,20 the greatest proportion of female settlers (36.8%) responded that their main reason for migration was to marry someone in Australia’, with almost half of all female settlers married to an Australian. In contrast, no male respondents gave marriage as their main reason for migration. In Nagatomo’s Brisbane fieldwork,21 eight of the 26 permanent residents were married to Australian citizens. Though he provides no breakdown of their gender, half of these eight couples married after the Japanese partner had embarked on a working holiday to Australia. Based on his explanation of factors that account for the high number of young Japanese women engaging in overseas tourism and working holidays to Australia, it is likely that the intermarriage couples in his work also reflect the contemporary gender imbalance.

Statistical analysis of Japanese residents in Australia may reveal their diverse demographic and socioeconomic characteristics but is limited in its capacity to portray this diversity.22 In the case of Japanese-Australian intermarriage, the lack of statistical data provides no conclusive insights, though it would appear there is a tendency for the wife to be the Japanese partner. It is here that qualitative studies can make a significant contribution.

Satō’s interview-based ethnographic work examines the everyday lives and value orientations of Japanese migrants to Australia.23 Based on interviews with over 200 long-term residents, she identifies their overseas residency as motivated by the pursuit of a better quality of life rather than a desire to escape from economic hardship. She refers to them as lifestyle migrants, a phenomenon which is discussed in the following section. In her chapter on the bright side and dark side of cross- cultural marriage’, she refers to the gender imbalance and claims that the marriages of Japanese women and Australian men are statistically…more likely to endure’ than those of Japanese men to Australian women.24 However, her book is unreferenced and the source of this information is not given. She believes that these patterns in Japanese- Australian intermarriage are suggestive of cultural attitudes to gender and gender roles which categorise Japanese wives in two ways: those eager to escape gender restrictions from a still largely patriarchal Japanese society, or traditional women who come for other reasons and find themselves attractive because of their old-fashioned attitudes. In her presentation of the varied experiences and reflections of her Japanese informants, including war brides, those of Japanese wives dominate. Aside from reflections on unhappy and failed relationships, other matters they spoke of included difficulties with English, longings for Japanese food and the hassle of travel to Japan. Some Japanese partners also spoke of ensuring their children grew up with a fundamental knowledge of Japanese and a positive image of Japan.

Owen’s study of interracial marriage in Australia includes anecdotes from Japanese-Australian couples.25 Two couples are featured in a chapter on interracial marriage in the 1950s, and another four are studied as a part of modern marriages of the 1990s. The stories of the two war brides are generally positive accounts of being welcomed by in-laws and accepted into Australian society, unlike those of alienation and hardship which appear in more comprehensive examinations of these women’s experiences.26 The contemporary group also includes couples in which the wife is Japanese. Matters of language, child bilingualism, and visits to Japan are mentioned among others, however only a small amount of space is dedicated to each couple and they are introduced with little background information.

Other works which investigate intermarriage in Australia make very few references to Japanese-Australian couples. In a paper by Luke and Luke on their three – year study of interracial Australian families, the language maintenance activities of a Japanese mother are briefly mentioned.27 These activities include using Japanese with her son at home, having him attend supplementary schooling on Saturdays, and sending him to Japan to study for six months. Penny and Khoo’s comprehensive study of intermarriage in Australia combines a statistical overview with case studies that describe the context and experiences of Australians and their partners from the United States, the Netherlands, Italy, Lebanon, Indonesia, China and Singapore.28 Japanese-Australian intermarriage is not discussed in the overview and data related to Japan-born spouses are included in only a portion of the supporting tables and graphs.

The omission of contemporary Japanese-Australian couples in discussions of intermarriage in Australia reflects the larger absence of Japan and the Japanese in works which examine Asians in Australia.29 This may be attributable to the comparatively small Japanese presence in Australia, and that the Japanese ethnic community has never established itself to the extent of other communities.30 Statistical data is unable to provide a basic characterisation of Japanese-Australian couples, though it appears certain that the wife in these unions tends to be Japanese. From the limited qualitative work that exists, matters of language, both of the Japanese partner’s English ability and the transmission of Japanese to their children, and travel to Japan were touched upon by informants.

Japanese Lifestyle Migration to Australia

Understanding the phenomenon of Japanese lifestyle migration to Australia can provide insight into contemporary Japanese-Australian intermarriage. Satō uses the term lifestyle migrant in her description of long-term Japanese residents who have come to Australia since the 1970s.31 The fundamental characteristic of this migrant type is the primary importance of lifestyle factors in their decision to migrate, as opposed to the pursuit of improved economic conditions and employment opportunities. Japanese lifestyle migrants often belong to one of three broad categories: senior citizens, women, or individuals with special skills. Satō differentiates these from corporate sojourners and their families who live in comfortable circumstances with the financial backing of their company. However, like corporate sojourners who leave Japan knowing they will return once their posting is finished, lifestyle migrants also appear to have the same intention. She observes that they hesitate to commit to settlement in Australia and are essentially long-term sojourners who happen to be in Australia and want to enjoy the amenities and comfort that this affords for a considerable period of their life’.32

The importance of lifestyle factors for Japanese migration to Australia have been similarly referred to by other researchers, and the phenomenon of Japanese lifestyle migration has also informed recent work on Australia’s Japanese communities.33 Nagatomo further develops Satō’s characterisation of lifestyle migrants, identifying three key factors: (a) They are less motivated by economic concerns than other Asian migrants; (b) many do not migrate permanently, except for those with Australian partners; and (c) they often retain Japanese citizenship, return regularly to visit Japan and maintain ties with their home community in Japan. While the first factor remains common with Satō, slight differences are apparent in the second and third factors.

In his second factor, Nagatomo allows for the likelihood that Japanese married to Australians will remain permanently. On the other hand, Satō categorises women who are married to Australian men as circumstantial migrants. Circumstantial migrants have come by force of circumstance’ and include children born in Japan but raised and educated in Australia following their parents’ migration, as well as middle- aged women who accompany adult children who have migrated.34 It is difficult to reconcile circumstantial migrants within the lifestyle migration phenomena. In the case of intermarriage, marriage is understood to account for their migration and is unrelated to dissatisfaction with their quality of life in Japan. In other words, they are here because they married an Australian. However, while this may have resulted in the long-term settlement of many Japanese women in Australia, their motivations and decisions prior to this must also be considered. Previously, such women were often tourists, students, or working holidaymakers with akogare for foreign, particularly Western, experiences and lifestyles. 35 Marriage may be the discrete event which draws attention, but is one part of a dynamic and ongoing migration process. Accordingly, Japanese who marry Australians and settle in Australia hold an ambiguous place within the lifestyle migration phenomenon.

In regards to the third factor, it is estimated that only one in five Japan-born residents are naturalised citizens, while the overall rate of Australian citizenship among overseas born residents is approximately 75%.36 This tendency to retain Japanese citizenship has been discussed by a number of researchers.37 Their explanations draw upon a variety of factors including mental and psychological attachment to Japan, minimal differences between citizenship rights and permanent residency, no dual citizenship arrangements, and practical reasons for retaining the privileges of Japanese citizenship. Satō does not mention regular return visits or the maintenance of social networks in Japan, though the former are often raised in discussions of the language and cultural maintenance activities of Japanese families in Australia.38

Japanese lifestyle migration remains undertheorised and has yet to pay explicit attention to the role of gender in migration. Nevertheless, the characteristics of Japanese lifestyle migrants to Australia outlined above provide useful starting points for this investigation of the diasporic experiences of Japanese wives in Japanese-Australian intermarriage families. It is anticipated that similar tendencies in social networks and return visits to Japan will exist.

Methodology

This study employs a qualitative research methodology, suitable for undertaking flexible research which can account for subjective realities.39 Ethical clearance to conduct the project was applied for and granted in accordance with the guidelines of the ethical review process of the University of Queensland.

Four participant couples who satisfied the following criteria were recruited for this study: (a) Married couples comprised of a Japanese wife and Australian husband who were both born and raised as citizens in their respective countries of origin; (b) parents with at least one child currently undertaking compulsory education; (c) current residents of South East Queensland. These criteria reflect the dominant pattern of gender imbalance, assumed tendency for parents of school-aged children to have made a long-term commitment to settlement in their current location, and the need to conduct face-to-face interviews with participants in a timely and cost-effective manner. Fortunately, South East Queensland is a common destination for both Japanese tourists and migrants, and the gender imbalance of this region’s Japanese residents is an accurate reflection of national figures.40

Personal and professional acquaintances were approached for assistance in locating suitable couples, in a form of snowball sampling.41 Unsurprisingly, this sampling method resulted in the involvement of participant couples who knew each other through their local Japanese social networks. However, the important role of these networks in the wives’ diasporic experiences only became apparent while conducting the interviews.

Each couple were provided an information sheet and short questionnaire in both English and Japanese. The questionnaires, based on those developed by other researchers42, solicited demographic and background information on the family. In-depth interviews43 of approximately one hour in duration were conducted with each couple in their own home and audio recorded. As I am fluent in both English and Japanese, participants were assured that they could freely express themselves in either language, though English was the main, common language used by all participants.

Wives and husbands were interviewed together to increase the number of data sources for each family. The wives’ observations and opinions of themselves and their family were enriched, clarified, and sometimes challenged by their husbands. It was understood that this arrangement could limit the wives’ participation, however the instances of disagreement and tension during the interviews suggest both partners felt sufficiently comfortable to express themselves and raise differences of opinion.

The technical and interpretational issues of transcription were taken into consideration.44 My transcriptions of the interviews were in full and largely verbatim, leaving grammatical mistakes such as confused word order and incorrect use of tense unedited. Analysis was conducted using an eclectic, bricolage approach commonly employed to interview data.45 Patterns and themes emerging from the data which resonated with the characterisations of Japanese-Australian intermarriage and Japanese lifestyle migration were identified and explored further.

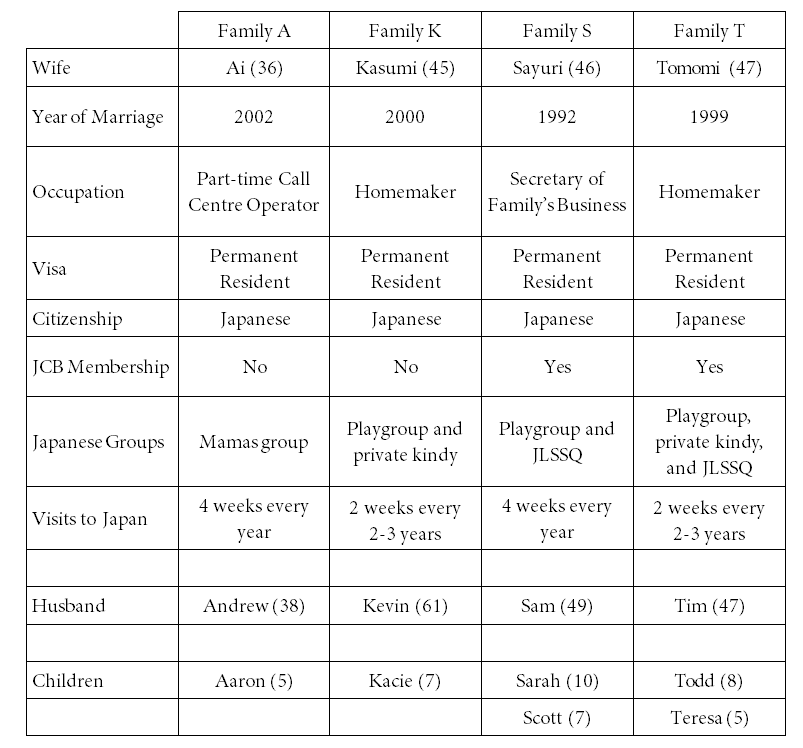

Due to space constraints, a detailed profile of each participant couple is not included here. Instead, a summary of basic demographic information is provided in the table below. Participants’ names are replaced with pseudonyms.

Table 1: Participant wives and their families

Local Relationships: Networks with the Japanese Community

The Japanese lifestyle migrant community in Australia involves social networks that are deterritorialised, autonomous, and non-organisational.46 The extensive networks and regular interactions between the four wives and local Japanese reflect this. In general, the birth and raising of children prompted them to search for and develop supportive social networks. These networks were based around informal mothers groups and semi-formal playgroups whose participants were almost exclusively other Japanese women married to Australian men with children of similar age. Although the wives explained that the purpose of attending these groups was to provide their children with an opportunity to play together and speak Japanese, their husbands pointed out that the groups also served as support groups for mothers. Here, a combination of instrumental and personal motivations is evident.

Three couples spoke of attending activities held by official Japanese organisations for local intermarriage couples in the early stages of their married life. However, they discontinued their involvement before forming any close friendships. The reasons given for this were the small size of the groups and disinterest in the type of activities. Another possible explanation may be the somewhat contrived nature of these gatherings, the common thread being participants’ intermarriage instead of a shared interest or activity. This interpretation is supported by the circumstances under which the wives, as mothers, came to form close relationships with other local Japanese.

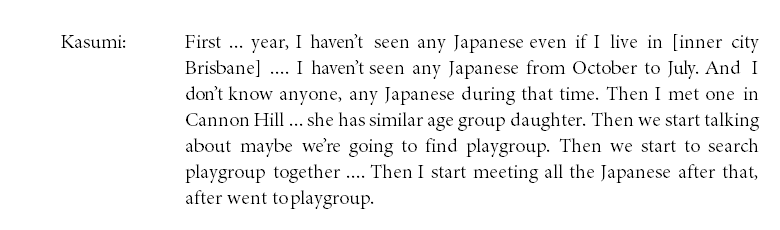

Motherhood was the catalyst for the establishment of important and lasting social networks. Kasumi’s recollection on her first year in Brisbane before moving to the Brisbane Valley illustrates this point:

The period following her arrival appears similar to many war brides who rarely encountered other Japanese. Yet she did not express any feelings of alienation or loneliness which are characteristic of war bride experiences.47 It is interesting that a chance meeting with another Japanese mother and her child coincided with a common goal to search for a playgroup. Arguably, had they not been mothers with children of similar age then the encounter may not have continued beyond a friendly greeting. This reflects the observation that lifestyle migrants in Brisbane’s local Japanese community participate deliberately and selectively in networks which fulfil particular needs at particular times, as opposed to engaging regularly and formally with established Japanese organisations.48

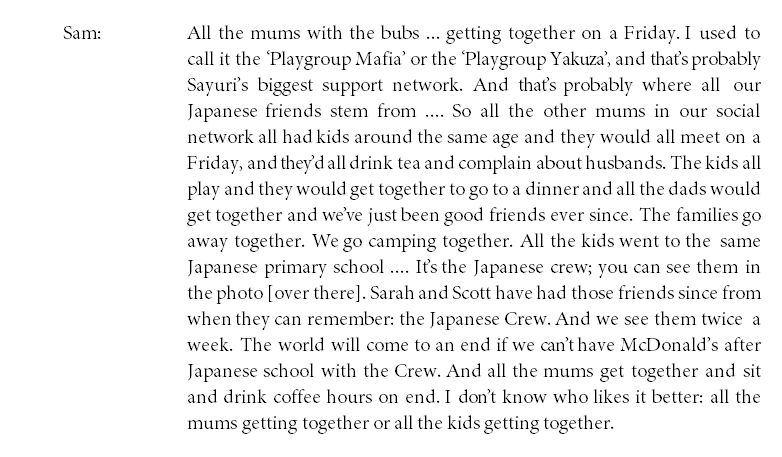

Kasumi, Sayuri, and Tomomi attended the same Japanese playgroup, based at a church on Brisbane’s southside, from the time their children were two. The use of such facilities reflects the deterritorialised nature of the Japanese ethnic community and the autonomous networks of local Japanese, particularly lifestyle migrants.49 In this case, a place with no enduring connection to the Japanese community is appropriated by the playgroup and transformed into an exclusive Japanese space for a couple of hours each week. Sayuri’s husband provided an interesting overview of the playgroup and its role in their family:

The reasons for being involved in such playgroups are directly related to the benefits its participants derive from it. For the mothers, it is a time and place where they can comfortably associate with other Japanese women, of similar migrant and intermarriage experiences, in their first language. It is also an environment that supports the acquisition and maintenance of their children’s Japanese through interaction with other similar children. Here, social networks that gather and concentrate the wives’ cultural capital at an arranged time and place support the intergenerational transmission and reproduction of capital within the family.50

As the children outgrew playgroup and started kindergarten or school, some continued on to the Japanese Language Supplementary School of Queensland (JLSSQ). Those who did brought with them their existing social networks, which now appear to have blended with those of other students and their families who come from other parts of Brisbane. Kasumi’s daughter is one who has not continued on, choosing to pursue weekend dance and drama lessons instead of studying Japanese on Saturday mornings. She no longer meets regularly with any of her Japanese’ friends, and her separation from this social network is likely to have contributed to her sudden loss of Japanese halfway through the first grade. Unfortunately, maintaining children’s language skills is a losing battle for most intermarriage families in Australia.51 Interestingly, Kasumi herself still maintains her friendships with other mothers from the playgroup and occasionally attends JLSSQ activities, such as its fundraising bazaar. This shows the important and continuing role these social networks play as personal bonds, even once initial motivations for doing so are no longer a priority.

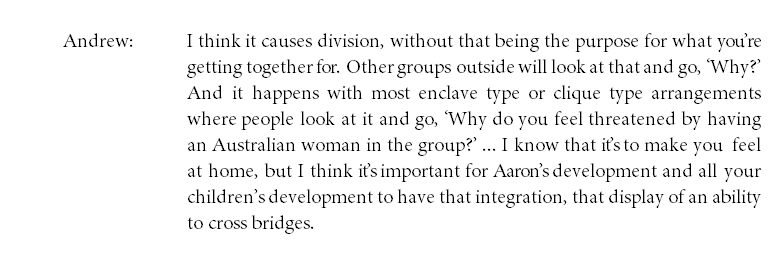

Ai belongs to a separate group of about eight Japanese mothers who have married Australian men and bought properties in the local housing estate. Some are friends she has known from her time as a single working holidaymaker on the north side of Brisbane. These wives do mama nights, let the kids play together and barbecues’ and their husbands are also forming links.’ While this sounds quite similar to Sam’s overview of the playgroup above, Ai’s husband was not so positive. Instead, he was critical that there is absolutely not a single Aussie girl who is involved’:

To Ai, the reason why Australian women were not a part of her Japanese social group was obvious: We talk in Japanese all the time.’ She defended herself further, explaining that she chatted with the Australian mums’ of her son’s friends at school. In response to Andrew’s suggestion that she could include those mothers in their mamas’ group, she made it clear that the exclusivity offered by this group, beginning with its members’ and their native language, is especially important to her:

Being a member of official organisations, such as the Japanese Club of Brisbane (JCB), and participating in the activities these offer has not played a significant role in any of the families social networks. Families S and T are members for the sole reason that it is a condition of their children’s entry into the JLSSQ. Any involvement in club activities was directly connected to the school, such as fund-raising bazaars, picnics, and culture days. This again reflects existing observations of network participation that fulfils particular needs at particular times52. When asked whether they would be members if it were not a condition of enrolment in the JLSSQ, both families were unsure. Sayuri continued:

Interestingly, though the wives in this study have established and maintained small support groups for the personal and instrumental motivations discussed above, they are keen to limit their involvement with official organisations which operate to provide similar support networks and resources. This is an example of the autonomous operation of grassroots level networks within the Japanese ethnic community.53 Kasumi, who has never been a member, explained why she avoids organisational involvement:

Dissatisfaction with facets of life in Japan and Japanese society is one reason attributed to the increase in Japanese lifestyle migrants to Australia, as well as young Japanese women embarking on working holidays.54 Yet the existence of grassroots level networks, and especially the playgroups and mamas’ groups of these four wives, indicate a strong interest in remaining connected with the Japanese community. Kasumi’s comments suggest that selective involvement with official organisations and a preference for autonomous networks may be attributable to a dislike of the hierarchical nature, formalities, and obligations of interpersonal relationships in Japanese society.

Remote Relationships: Trips to Japan

A characteristic of Japanese lifestyle migrants to Australia is their regular return trips to Japan.55 Such visits were common to the four families. Wives returned with their children for a period of two to four weeks over the Christmas and New Year holiday, either yearly or once every two to three years. Husbands did accompany them on such visits, though usually only half as often and for a shorter length of time. Work commitments were cited as keeping them from going and staying longer, though economic considerations appeared to play a factor as well.

The main reason for the wives’ regular trips to Japan was to see family and friends. Grandparents, in particular, were keen to see their young grandchildren, and in one case have been contributing financially to ensure they visit. Ai recalled that after the birth of her son she felt the need to be closer to her parents and has returned with Aaron every year. The ailing health of elderly parents among other wives provoked a sense of urgency; Tomomi spoke of wanting to see her mother as much as I can because I don’t want to regret it later.’ This is an example of the burden of guilt and regret of separation’ commonly experienced by intermarriage couples.56

Other common reasons for their visits were based upon what they did not have access to and missed as a part of everyday life in Australia. The affordability and convenience of modern air travel allows for return visits to bond with the homeland, as well as stock up on tangible, consumable aspects of home. This is quite different to the experiences of war brides, many of who only returned to Japan several decades after migrating and relied on local contacts and sailors for limited access to items from home.57 Tomomi enjoys reading and buys up on second hand books when she returns. In addition to forms of entertainment, real’ Japanese food was another thing spoken of fondly. Intangibles were also important. For Ai, not knowing what they think about, currently talk about’ was what she missed when away from Japan. Sayuri also spoke of loss:

Accordingly, for the wives in this study a return visit is not considered a holiday. This was raised at the end of one interview, and clearly illustrates the ongoing presence of the homeland in their diasporic experiences:

Two families divided their time in Japan between seeing family and friends, and travelling within the country. Travel involved activities they would not normally do in Brisbane, such as skiing. Travel was a way to introduce husbands and children to Japan and its culture. Kasumi explained her family would plan new trips each time to show Kevin and Kacie different parts of the country. Kasumi’s mother would also join them and introduce aspects of traditional Japanese culture in her beloved Kyoto.

Families A and S spoke of how beneficial the yearly trips were to the maintenance and development of their children’s Japanese. Living in the wives’ parental homes and meeting with extended family provided a near exclusive Japanese language environment, particularly when fathers were absent. Just as their social networks do in Australia, these visits assist in the intergenerational transmission and reproduction of the wives’ cultural capital. Sayuri’s children attend the local elementary school for three weeks leading up to the New Years break. This provided the children with a different experience’, particularly beneficial to language learning:

For intermarriage couples with a migrant partner whose parents are still overseas, the maintenance of ties often requires a large commitment of the couple’s assets.58 Many of the families in this study were concerned about the cost of their trips to Japan. Returning had become increasingly expensive as children were born and grew older. The economic burden increased even more for wives whose hometown is outside of Japan’s major cities. For Tomomi and Tim, taking the train from Tokyo to the Tōhoku region means an additional $1000 in overall transport costs. For Ai and Andrew in particular, the cost of trips was a clear source of tension. She considered it reasonably affordable, however her husband abruptly disagreed:

This is an interesting twist on the sending of remittances and financing of grandparents’ fares and extended stays in Australia by intermarriage families with an Asian partner, particularly ethnic Chinese.59 Ai plays down the economic aspects of the visits and even launders’ the money her parents provide for these through her personal savings. Nevertheless, her husband is uncomfortable with her parents paying:

To Ai who misses home, these visits are a necessity. On the other hand, to Andrew such holidays’ are a luxury. Nevertheless, not all the wives feel this way. Kasumi’s feelings towards Japan are different to those expressed above by Sayuri and Ai:

Similarly, not all families referred to the trips as a way of providing their children with an opportunity to develop their Japanese language skills. Tomomi and Tim spoke of their misgivings about the competitive Japanese education system. Tim was also hesitant to place his children in the local schools during trips like Family S did, believing that trying to fit into a new class’ was a disruption’ that must depend a lot on personalities.’ His wife also alluded to other Japanese-Australian intermarriage families whose children had disliked the experience and refused to go.

Conclusion

The entry of these four Japanese wives into motherhood was found to be their impetus for forming important social networks with other local Japanese. These networks were based around informal and semi-formal playgroups whose participants were predominantly other Japanese women with children of similar age and married to Australian men. For the mothers, these groups provided a time and place to bond in their native language with other Japanese women of similar experiences. It also facilitated the transmission and reproduction of cultural capital, in particular the Japanese language, to their children. As children grew older and moved on to supplementary schooling or chose to engage in other activities, these networks continued to play an important role in the wives’ social lives. While enrolment in the JLSSQ required JCB membership, their associations with local Japanese were still based primarily upon friendships and participation in autonomous networks rather than official organisations.

Regular visits to Japan were common to all four wives and were focused on engagement with existing family and friendship networks. Though regarded as holidays by their husbands, for the wives these trips were important opportunities to return home and gain access to experiences and items they missed from everyday life in Australia. Two of the wives divided their time between social engagements and travel, one purpose of which was to introduce husbands and children to Japan and its culture. An important benefit of staying with Japanese relatives and attending local schools for those couples actively fostering their children’s bilingualism was the exposure of their children to an almost exclusively Japanese language environment. The economic burden of yearly travel was a noticeable source of tension in one interview and shows how travel to the migrant partner’s country may be perceived differently within an intermarried couple. In this case, a wife’s necessity to return home’ is in conflict with her husband’s feeling that such holidays’ are a luxury.

This study did not attempt a comparative analysis of different intermarriage cohorts, however it is clear that the diasporic experiences of the contemporary generation of Japanese women are fundamentally different from those of the war brides. Unlike the latter who often concealed their Japaneseness in an attempt to assimilate into a post-war White Australia, the former now retain and maintain their Japanese identity, utilising it to develop supportive networks, in a multicultural Australia. As a result of increasing globalisation and advances in technology, they have not faced the isolation and alienation from country, language, family, friends, news, food, and entertainment that those who came during the 1950s endured. The contemporary experience of intermarriage for these women and their families is decidedly transnational.

The small scale of this study and its limited focus present a variety of opportunities for further inquiries into the diasporic experiences of Japanese women in Japanese – Australian intermarriage families. In particular, the socioeconomic circumstances and employment of participants could be considered to determine how social networks may be affected by mothers’ need to work and reduced capacity to socialise. Comparative work with intermarriage families settled in Japan or Japanese families in Australia may reveal different patterns in social networks or engagement with educational institutions. Additionally, research into Japanese women who have separated from their Australian partners would add further dimensions to the understanding of migration as a dynamic and ongoing process.

References

ABS, Migration, Australia (No.3412.0) (Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2008). Retrieved 10 September 2008, from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3412.02006-07?OpenDocument.

Ackland, M., and Oliver, P. (eds.), Unexpected Encounters: Neglected Histories behind the Australia-Japan Relationship (Clayton: Monash Asia Institute, 2007).

Atsumi, R., A Demographic and Socio-economic Profile of the Japanese Residents in Australia’, in Coughlan, J. E. (ed.), The Diverse Asians: A Profile of Six Asian Communities in Australia (Brisbane: Griffith University, 1992), pp. 11-31.

Bourdieu, P., On the Family as a Realised Category’, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 13, no. 3 (1996), pp. 19-26,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/026327696013003002

Brändle, M. (ed.), Multicultural Queensland 2001: 100 Years, 100 Communities, a Century of Contributions (Brisbane: Multicultural Affairs Queensland, 2001).

Breger, R., and Hill, R. (eds.), Cross-cultural Marriage: Identity and Choice (Oxford: Berg, 1998).

Coughlan, J. E., Japanese Immigration in Australia: A Socio-demographic Profile of the Japan-born Communities from the 1996 Census. Paper presented in December 1999 at the Japanese Studies Association of Australia Conference.

Coughlan, J. E., and McNamara, D. J., Asians in Australia: Patterns of Migration and Settlement (South Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia, 1997).

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S., Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research’, in Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2005), pp. 1-32.

DIAC, Community Information Summary: Japan-born (Canberra: Department of Immigration and Citizenship). Retrieved 10 September 2008, from http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/comm-summ/ index.htm.

DIMIA, The People of Australia (Canberra: Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, 2003).

Flick, U., An Introduction to Qualitative Research (London: Sage, 2006).

Jones, P., and Mackie, V. (eds.), Relationships: Japan and Australia 1870s-1950s (Melbourne: University of Melbourne, 2001).

Kelsky, K., Women on the Verge: Japanese Women, Western Dreams (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9780822383277

Kinenshi Henshū Iinkai, Ōsutoraria no Nihonjin: Isseiki wo koeru Nihonjin no Ashiato (Asquith: Zengō Nihon Kurabu, 1998).

Kvale, S., Doing Interviews’, in Flick, U. (ed.), The SAGE Qualitative Research Kit (London: Sage, 2007), vol. 2. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208963.

Luke, A., and Luke, C., The Difference Language Makes: The Discourses on Language of Inter-ethnic Asian/Australian Families’, in Ang, I. (ed.), Alter/Asians: Asian-Australian Identities in Art, Media and Popular Culture (Annandale: Pluto Press, 2000), pp. 42-67.

Luke, C., and Luke, A., Interracial Families: Difference within Difference’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 21, no. 4 (1998), pp. 728-754,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/014198798329847

Meaney, N. K., Towards a New Vision: Australia and Japan through 100 Years (East Roseville: Kangaroo Press, 1999).

Mizukami, T., The Integration of Japanese Residents into Australian Society: Immigrants and Sojourners in Brisbane (Clayton: Monash University, 1993).

Mizukami, T., The Sojourner Community: Japanese Migration and Residency in Australia (Leiden: Brill, 2007).

MOFA, Kaigai Zairyū Hōjinsū Chōsa Tōkei (Tokyo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2006).

Nagata, Y., Unwanted Aliens: Japanese Internment in Australia (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1996).

Nagata, Y., Lost in Space: Ethnicity and Identity of Japanese-Australians 1945-1960s’, in Jones, P. and Oliver, P. (eds.), Changing histories: Australia and Japan (Clayton: Monash Asia Institute, 2001), pp. 85-99.

Nagata, Y., Gendering Australia-Japan Relations: Prostitutes and the Japanese Diaspora in Australia’, Ritsumeikan Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, vol. 11 (2003), pp. 57-70.

Nagata, Y., The Japanese in Torres Strait’, in Shnukal, A., Ramsay, G., and Nagata, Y. (eds.), Navigating Boundaries: The Asian Diaspora in Torres Strait (Canberra: Pandanus Books, 2004), pp. 138-159.

Nagata, Y., and Nagatomo, J., Japanese Queenslanders: A History. (Brisbane: Bookpal, 2007).

Nagatomo, J. (ed.), Japan Club of Queensland Nijūshūnen Kinenshi: Ijū no Katari (Brisbane: Japan Club of Queensland, 2007).

Nagatomo, J., Datsu-ryÅdoka sareta Komyuniti’, in Ōtani, H. (ed.), Bunka no Gurōkarizēshon wo yomitoku (Fukuoka: Genshobō, 2008), pp. 185-204.

Nagatomo, J., Globalisation, Tourism Development, and Japanese Lifestyle Migration to Australia’, in Nault, D. M. (ed.), Development in Asia: Interdisciplinary, Post-neoliberal, and Transnational Perspectives, (Parkland: Brown Walker Press, 2008), pp. 215-236.

Owen, J. D., Mixed Matches: Interracial Marriage in Australia (Sydney: University of New South Wales, 2002).

Penny, J., and Khoo, S., Intermarriage: A Study of Migration and Integration. (Canberra: Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, 1996).

Robson, C., Real world research: A resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002).

Satō, M., Farewell to Nippon: Japanese Lifestyle Migrants in Australia (Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press, 2001).

Shiobara, Y., The Beginnings of the Multiculturalization of Japanese Immigrants to Australia: Japanese Community Organisations and the Policy Interface’, Japanese Studies, vol. 24, no. 2 (2004), pp. 247-261,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1037139042000302537

Shiobara, Y., Middle-class Asian Immigrants and Welfare Multiculturalism: A Case Study of a Japanese Community Organisation in Sydney’, Asian Studies Review, vol. 29 (2005), pp. 395-414,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10357820500398341

Silverman, D., Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction (London: Sage, 2001).

Sissons, D. C. S., Towards a New Vision: A Symposium on Australian and Japanese Relations (Sydney: Japan Cultural Centre, 1998).

Suzuki, A., Japanese Supplementary Schooling and Identity: Second-generation Japanese Students in Queensland, Unpublished thesis (University of Queensland: 2005).

Tamura, K., Michi’s Memories: The Story of a Japanese War Bride (Canberra: Australian National University, 2001).

Taylor, S. J., and Bogdan, R., Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource (New York: Wiley, 1998).

Tokita, A., Marriage and the Australia-Japan Relationship. Paper presented on 17 August 2007 at the 20th International Conference of the Japan Studies Association of Canada. Abstract retrieved 18 May 2008, from http://udo.arts.yorku.ca/jsac/jsac2007/.

Yamamoto, M., Language use in Interlingual Families: A Japanese-English Sociolinguistic Study (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 2001). https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853595417.

Yoshimitsu, K., Language Maintenance of Japanese Children in Morwell’, in Marriott, H. and Low, M. (eds.), Language and Cultural Contact with Japan (Melbourne: Monash Asia Institute, 1996), pp. 138-155.

Jared Denman

The University of Queensland

Jared Denman was awarded First Class Honours in Japanese at The University of Queensland in 2008, after completing an Arts (Japanese)/Education dual degree. He is currently a PhD candidate with the School of Languages and Comparative Cultural Studies and is examining the transnational experience of ageing among first-generation migrants from the local Japanese diaspora.

- Historical works include: Ackland & Oliver, Unexpected Encounters’; Jones & Mackie, Relationships’; Meaney, Towards a New Vision’; Nagata, Unwanted Aliens’; Nagata, The Japanese in Torres Strait’; Sissons, Towards a New Vision’. Commemorative works include: Kinenshi Henshū Iinkai, Ōsutoraria no Nihonjin’; Nagatomo, Japan Club of Queensland Nijūshūnen Kinenshi’. A combination of the two includes Nagata & Nagatomo, Japanese Queenslanders’. ↩

- Brändle, Multicultural Queensland 2001′. ↩

- Mizukami, The Integration of Japanese Residents into Australian Society’. ↩

- Nagatomo, Datsu-ryōdoka sareta Komyuniti’. ↩

- Mizukami, The Sojourner Community’; Shiobara, The Beginnings of the Multiculturalization of Japanese Immigrants to Australia’; Shiobara, Middle- class Asian Immigrants and Welfare Multiculturalism’. ↩

- Mizukami, The Sojourner Community’. ↩

- Satō, Farewell to Nippon’. ↩

- Nagatomo, Datsu-ryōdoka sareta Komyuniti’; Nagatomo, Globalisation, Tourism Development, and Japanese Lifestyle Migration to Australia’. ↩

- Nagata, Lost in Space’; Suzuki, Japanese supplementary schooling and identity’; Tamura, Michi’s Memories’. ↩

- Nagata, Gendering Australia-Japan Relations’. ↩

- Breger and Hill, Cross-cultural Marriage’; Luke and Luke, Interracial families’; Owen, Mixed Matches’. ↩

- Tokita, Marriage and the Australia-Japan relationship’. ↩

- Penny and Khoo, Intermarriage’, p. 2. ↩

- Nagatomo, Datsu-ryōdoka sareta Komyuniti’; Nagatomo, Globalisation, Tourism Development, and Japanese Lifestyle Migration to Australia’. ↩

- Nagata, Lost in Space’. ↩

- ABS, Migration, Australia’. ↩

- DIMIA, The People of Australia’. ↩

- ABS, op. cit.; MOFA, Kaigai Zairyū Hōjinsū Chōsa Tōkei’. ↩

- Coughlan, Japanese Immigration in Australia’. ↩

- Mizukami, The Sojourner Community’. ↩

- Nagatomo, Globalisation, Tourism Development, and Japanese Lifestyle Migration to Australia’. ↩

- Atsumi, A Demographic and Socio-economic Profile of the Japanese Residents in Australia’. ↩

- Satō, op. cit. ↩

- Ibid., p. 127. ↩

- Owen, op. cit. ↩

- Nagata, Lost in Space’; Tamura, op. cit. ↩

- Luke and Luke, The Difference Language Makes’. ↩

- Penny and Khoo, op. cit. ↩

- Such as Coughlan and McNamara, Asians in Australia’. ↩

- Nagata, Lost in Space’; Nagata & Nagatomo, op. cit. ↩

- Satō, op. cit. ↩

- Satō, op. cit., p. 2. ↩

- The importance of lifestyle factors are acknowledged by Mizukami and Shiobara, while lifestyle migration informs the work of Nagata and Nagatomo, and Nagamoto. ↩

- Satō, op. cit., p. 22. ↩

- For a discussion of akogare see Kelsky, Women on the Verge’. ↩

- DIC, Community Information Summary’. ↩

- Atsumi, op. cit.; Mizukami, The Sojourner Community’; Satō, op. cit. ↩

- Suzuki, op. cit.; Yoshimitsu, Language maintenance of Japanese children in Morwell’. ↩

- Denzin and Lincoln, Introduction’; Flick, An Introduction to Qualitative Research’; Robson, Real world research’; Silverman, Interpreting Qualitative Data’. ↩

- ABS, op. cit.; MOFA, op. cit. ↩

- Robson, op. cit. ↩

- In particular Suzuki, cit. and Yamamoto, Language use in interlingual families’. ↩

- As outlined by Taylor and Bogdan, Introduction to qualitative research methods’. ↩

- Kvale, Doing Interviews’. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Nagatomo, Datsu-ryōdoka sareta Komyuniti’. ↩

- Nagata, Lost in Space’. ↩

- Nagatomo, Datsu-ryÅdoka sareta Komyuniti’. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Bourdieu, On the Family as a Realised Category’. ↩

- Luke and Luke, The Difference Language Makes’. ↩

- Nagatomo, Datsu-ryōdoka sareta Komyuniti’. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Mizukami, The Sojourner Community’; Nagatomo, Globalisation, Tourism Development, and Japanese Lifestyle Migration to Australia’. ↩

- Nagatomo, Datsu-ryōdoka sareta Komyuniti’. ↩

- Penny and Khoo, op. cit., p. 208. ↩

- Nagata, Lost in Space’. ↩

- Penny and Khoo, op. cit., p. 208. ↩

- Penny and Khoo, op. cit., p. 208. ↩