A Centaur in Salaryman’s Clothing: Parody and Play in est em’s Centaur Manga

Published July, 2016

Pages 55-76

https://doi.org/10.21159/nvjs.08.03

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney and Anne Lee, 2016

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

New Voices

in Japanese Studies

Volume 8

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2016

Abstract

Japanese manga artist est em (esu to emu) is notable for blurring genre boundaries and subverting established conventions in various publications since her debut in 2006. Two of her works, Hatarake, kentaurosu! (Work, Centaur!’) and equus, focus exclusively on male centaurs in homosocial settings. Classified as shōjo (girls’) manga and BL (boys’ love’) manga respectively, these two works allow female readers to enjoy the pleasures of homoerotic subtexts and intertextual parody. This paper examines how conventions of sexuality and gender, particularly hegemonic masculinity and heterosexuality, are constructed/deconstructed in est em’s centaur manga using the framework of intertextuality, with particular emphasis on parody, pleasure and play. By placing centaurs in realistic, everyday settings, these works present a critique of Japan’s contemporary salaryman culture, while also highlighting issues of alienation and otherness that both female readers and gay men face in their daily lives.

INTRODUCTION

In the vast world of manga there is a genre for every interest, no matter how obscure. From realistic sports dramas to tales of princesses from other worlds, manga span a wide range of genres and themes (see Ito 2005; Schodt 1983). Greek mythology, for example, influenced many manga series, including smash hits such as Seinto seiya [Saint Seiya: Knights of the Zodiac; 1986] and Bishōjo senshi sērā mūn [Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon; 1991].1

Centaurs, in particular, are prominently featured in a number of manga published in 2011: Sentōru no nayami [A Centaur’s Life] by Kei Murayama, Zeusu no tane [Zeus’ Seed’] by Kōsuke Iijima, Ryū no gakkō wa yama no ue [The Dragon’s School is on the Mountain Top’] by Ryōko Kui, and equus and Hatarake, kentaurosu! [Work, Centaur!’] by est em (えすとえむ; esu to emu).2 However, instead of focusing on centaurs in exotic, mythological settings, each of these narratives insert centaur characters into normal, everyday settings.3 Sentōru no nayami focuses on the mundane aspects of living as a centaur in a world closely resembling modern Japan but inhabited exclusively by fantastical creatures. Meanwhile, Zeusu no tane and Ryū no gakkō wa yama no ue both present centaurs coexisting with humans. est em’s two centaur works, equus and Hatarake, kentaurosu!, follow this same trend of placing centaurs in a variety of real-world situations, centering particularly around male centaurs in homosocial settings. The juxtaposition of these half-human, half-horse creatures with familiar, real-world environments highlights the centaurs’ otherness: although their upper bodies are identical to those of humans, their bottom horse-halves pose numerous obstacles to inhabiting a world built primarily for bipedal humans. By inserting male centaurs in relatable situations for readers, est em’s works offer opportunities to explore culturally established gender and social structures through the use of intertextual parody and play.

This article examines how social and gender conventions, particularly hegemonic masculinity and heterosexuality, are constructed/deconstructed in est em’s centaur manga using the framework of intertextuality, with particular emphasis on parody, pleasure and humour/laughter. It analyses how parody is utilised in Hatarake, kentaurosu! and equus in both social and literary contexts, exploring how manga aimed at a female audience incorporates criticism of gender and issues of inequality while simultaneously transforming such issues into sources of pleasure. Linda Hutcheon (1985) defines parody as ”ironic playing with multiple conventions, [and] extended repetition with critical difference” (7). The pleasure of decoding a parodic text and the playful way in which gender restrictions are subverted within this type of manga can also be linked back to discourse on the subversive power of women’s laughter to disrupt patriarchal authority and social systems (Cixous 1975). While it may seem obvious to mention that girls and women read because it brings pleasure, literary criticism tends to neglect the role of pleasure in the act of reading (Barthes 1973). Even so, the subversion of established hierarchies such as gender norms in women’s literature is often linked to pleasure and humour (Aoyama 1994), making it necessary to explore how themes of textual pleasure such as laughter and play aid in an analysis of parody in these manga. Rather than demanding immediate, radical change to the gender and social status quo, these texts engage with restrictive social and gender structures through playful subversion (Aoyama and Hartley 2010, 7).

As Tomoko Aoyama (2012) notes, instead of ”directly protesting patriarchal and heterosexist oppression,” intertextual parody can ”transform existing inequalities and potential threats into pleasure and gratification” (66). Parody may not always be humorous in nature, but the ”intertextual pleasure” experienced by ”knowing readers” who move between multiple texts offers numerous levels through which readers can enjoy a particular work (Hutcheon 2006, 117). Through playful transformation and allusion, equus and Hatarake, kentaurosu! present an alternative to a repressive patriarchal society, despite the almost complete absence of female characters. These narratives are greatly enhanced by what Aoyama describes as ”BL literacy,” or ”the ability to read and write/draw male homoerotic narratives according to, while often at the same time subverting, the specific conventions of this genre” (2012, 66). BL, an acronym for boizu rabu (ボイズラブ; boys’ love’),4 denotes male-male romance manga aimed at a female audience, often containing explicit sexual material. BL literacy not only informs the way readers engage with est em’s BL narratives, but also her other works that do not fall within the genre.

Since making her professional debut in 2006 with the BL manga Shōga hanetara aimashō [Seduce Me After the Show], est em has repeatedly blurred the distinction between heternormative shōjo (少女; girls’) manga and homoerotic BL. While other centaur manga published in 2011 are marketed towards shōnen (少年; boy) and seinen (青年; young adult male) readers, est em’s equus and Hatarake, kentaurosu! are sold as BL and shōjo manga respectively. Shōjo manga initially emerged in the mid-1950s as a distinct marketing genre separate from shōnen, with roots in the shōjo culture established by shōjo shōsetsu (少女小説; girls’ novels) and sashie (挿絵; illustrations) popular among schoolgirls in the 1920s and 30s (Honda 2010, 13). Although Osamu Tezuka’s Ribon no kishi [Princess Knight; 1953] is often cited as the first shōjo manga, Yukari Fujimoto argues that many of the distinctive shōjo manga features such as large, star-filled eyes, unconventional panel layouts and expository narration were pioneered by Macoto Takahashi’s Arashi o koete [Beyond the Storm’], which began serialisation in 1958 (Fujimoto 2012, 24).

Shōjo manga became increasingly defined in the 1960s and 70s, and shōnen ai (少年愛; lit., boys’ love’) narratives featuring romantic relationships between beautiful young boys grew exponentially in popularity within the genre (McLelland 2000). These stories about love between boys were an outlet for readers, from adolescent girls to young adult women, to explore their sexuality without the risk of alienation, depicting love between equals and more graphic depictions of sex than was acceptable in heterosexual romances of the time (Ishida 2008). Now known as BL, this subgenre of shōjo manga remains a significant imaginary domain where readers are not restricted to mainstream culture’s rigid definition of heteronormative desire, thereby providing an escape from the negative elements of socially constructed female identity (Kan 2010, 55).

It is worthwhile to consider how the escape presented by BL and BL-informed narratives has the potential to inspire change. As Terry Eagleton (1983) asserts, ”rather than merely reinforce our given perceptions, the valuable work of literature violates or transgresses these normative ways of seeing, and so teaches us new codes for understanding” (68). Just as centaurs embody the best attributes of horse and man, est em’s equus and Hatarake, kentaurosu! do not neatly adhere to genre or social conventions, but instead combine and reconsider aspects of both. Blurring the lines between man and horse as well as shōjo and BL manga, these texts offer a complex look at the world of human and centaur interactions from the perspective of the female outsider. BL literacy enables readers to enjoy the pleasures of subverting traditionally homosocial situations through parody and play, while encouraging contemplation of alternatives to patriarchal norms.

HOMOEROTICISM AND HALF-BEASTS IN JAPANESE LITERATURE

Outside of traditional Greek mythology, human-animal hybrid creatures have long resonated with Japanese writers and artists. Named after the half- man, half-goat god Pan, the Pan Society (パンの会) was ”an organisation that sought to promote interaction between visual artists and poets and to imitate the café discussions of art and literature common to France in the late nineteenth century” (Angles 2011, 6). Some of Japan’s most important authors and artists of the early twentieth century attended the Pan Society, such as Jun’ichirō Tanizaki [1886—1965] and Kafū Nagai [1879—1959]. God of nature and shepherds, Pan was often associated with sexuality. According to Pan Society scholar Utarō Noda, author Mokutarō Kinoshita [1885—1945] selected a restaurant located by the Sumida River in Ryōgoku, Tokyo, for the society’s first meeting in December 1908 due to its association with old Edo culture and the Seine, the symbol of French art and literature (Aoyama 1992, 281). As noted by Aoyama, the society was heavily characterised by occidentalism and exoticism, valuing various aspects of Edo culture not due to nostalgia but for ”the same kind of exoticism as displayed by European artists, especially impressionists, in welcoming the ukiyoe prints” (Aoyama 1992, 282).

Similar to Pan, Greek centaurs were neither mortal nor immortal; they lived in forests, and were depicted as uncultured, impulse-driven creatures that amplify the complex dual natures of humans. Originating from the Greek Centaurus’, or Kentaurus’, centaurs were often associated with their love for ”sex, food, and alcohol” (Padgett 2003, 3). The kentaurosu‘ in est em’s Hatarake, kentaurosu! derives from the Greek Kentaurus’, while also humorously referencing Osamu Dazai’s mock-heroic tale Hashire Merosu [Run, Melos!]. One of the most prominent centaurs in Greek mythology is Chiron, a teacher, oracle, and healer who mentored numerous great heroes such as Achilles. Unlike Greek satyrs, which were a mixture of horse or mule and human characteristics, centaurs were not an amalgamation, but rather featured a divide at the waist between man and equine. Neither fully man nor fully horse, centaurs complicate classic divisions between animal/human and nature/civilisation. By occupying spaces also inhabited by humans, est em’s centaurs further problematise these distinctions. Although the concept of ”centaur” is never treated as fantastical within her narratives, the difficulties associated with inhabiting a world where centaurs are treated as a minority are present in all of her stories.

Before turning to est em’s manga, however, it is necessary to consider the long history that homosocial literature with homoerotic undertones (or, not infrequently, overtones) has in Japanese culture. Shōjo manga are often praised for widespread depictions of male-male romance (see Fujimoto 1998), but the roots of women writing male-male romance can be traced back as far as The Tale of Genji (源氏物語) in the early eleventh century. Historically, homoerotic literature in Japan was not an abnormality, but rather an ”elaborate cultural tradition” that, until the late nineteenth century, ”figured in the cultural imagination as a familiar literary trope, as a legitimate and widely accepted practice, and as a nexus of cultural value” (Vincent 2012, 3). During the Edo period [1603—1868], the terms nanshoku (男色; also read danshoku, meaning male eros’) and shudō or wakashudō (衆道・若衆道; the way of the youth)5 were used to describe male-male desire, referring specifically to the relations between adult men and young boys who had not yet completed the genpuku (元服)6 coming-of-age ceremony (Angles 2011, 5—6). When the publishing industry expanded in the Edo period, an increasing number of texts emerged extolling the virtues of cultivating the pleasures of men, indicating a growing interest in male-male eroticism among the cosmopolitan public (Angles 2011, 6).

In the early twentieth century, however, Japan moved increasingly toward a compulsorily heterosexual patriarchal society in an attempt to be seen by Western nations as more modern and enlightened. Cultural historian Gregory Pflugfelder (1999) notes that during the Meiji period [1868—1912], homoeroticism came to be ”routinely represented as barbarous,’ immoral,’ or simply unspeakable'” in popular discourse as Japan adopted Western rhetoric on sexuality (193). Increasingly viewed as uncivilised and immature, nanshoku was replaced with dōseiai (同性愛; lit., ”same-sex love”), a term informed by European notions of homosexuality that could be used to refer to both male-male and female-female desire. The shift toward compulsory heterosexuality seen in early twentieth-century Japan saw a rupture of what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (1992) theorises as the ”male homosocial continuum,” which connects ”men-loving-men” and ”men-promoting-the-interests-of- men” (3). Although dealing with British literature, Sedgwick notably drew the ”homosocial’ back into the orbit of desire,’ of the potentially erotic” in modern Western culture (1992, 1). Regarding Japanese literature in the early twentieth century, Keith Vincent (2012) notes that ”[Japan’s] newly heteronormative culture was unable and perhaps unwilling to expunge completely the recent memory of a male homosocial past now read as perverse” (3). Thus, while male-male eroticism is no longer privileged in Japan as it was in the Edo period and earlier, its long history in Japanese literary culture has been influential in the realm of manga.

NIOI-KEI AND BL LITERACY

To date, extensive research has been conducted in both English and Japanese in the areas of shōjo and BL manga. While there is still some inconsistency in the use of the term BL within scholarship (McLelland and Welker 2015, 5), this article uses Kayo Takeuchi’s (2010) definition of BL as ”a term that came into usage during the latter half of the 1990s, indicating, for the most part, original stories written/drawn by professional writers in both shōjo manga and shōjo shōsetsu issued by established publishing houses” (91) that focus on male-male romance. As McLelland and Welker note, while shōjo manga target female readers from pre-adolescence to young adulthood, many shōjo works have an actual readership that includes older women and male readers (4).

According to Junko Kaneda (2007), BL research generally takes two forms: a psychological approach exploring the appeal of homoerotic narratives to a predominantly female readership, or a gender studies approach that considers the subversive potential of the genre. Indeed, the majority of BL scholarship has largely focused on why girls and women read BL manga and what BL means for its readers and society (e.g., McLelland 2000; Ueno 1989; Wood 2006). Fewer scholars have looked at how the constantly evolving BL genre does not neatly adhere to any one definition, nor remain an untouched entity separate from shÅjo manga, and what this blurring of genres means for manga written by and for women. Indeed, Akiko Mizoguchi (2010) suggests that certain non-BL works would not exist without BL as a platform for ”examining the fundamental questions of sexuality, reproduction, and gender … within the framework of entertaining fiction with sexual depictions” (163). Kumiko Saito (2011) expands on this further, noting that the heterosexual romances in a number of successful manga for women such as Tomoko Ninomiya’s Nodame Kantābire [Nodame Cantabile; 2001] and Chika Umino’s Hachimitsu to kurōbā [Honey and Clover; 2000] are informed by the common BL trope of romances forming out of friendship based on ”matching abilities and competition” (188).

est em’s first centaur manga, Hatarake, kentaurosu!, notably falls within this spectrum of non-BL works informed by BL. Its varied publication history gives insight to the intended audience and potential readings of the text. The short stories that are compiled in Hatarake, kentaurosu! originally appeared in girls’ and young women’s manga magazines Kurofune ZERO [Black Ship ZERO’] and BE∙BOY GOLD.7 Though BE∙BOYGOLD targets a BL readership, none of the stories published in neither it nor Kurofune ZERO contain explicitly romantic relationships between men. Instead, these stories focus on centaurs living and working in modern Japan in predominantly homosocial settings. Unlike BE∙BOYGOLD, Kurofune ZERO does not serialise BL manga. However, it has featured a slice-of-life series titled Fujoshi no hinkaku [Fujoshi’s Dignity’; 2008] that focused on the lives of two fujoshi (腐女子), or female BL fans. This suggests that Kurofune ZERO readers identify as, or relate to, fujoshi, despite the fact that the magazine does not target a specifically BL readership. Furthermore, est em’s large body of BL publications may lead readers of Hatarake, kentaurosu! to imagine the male protagonists in a romantic relationship, even though it is never depicted in the manga.

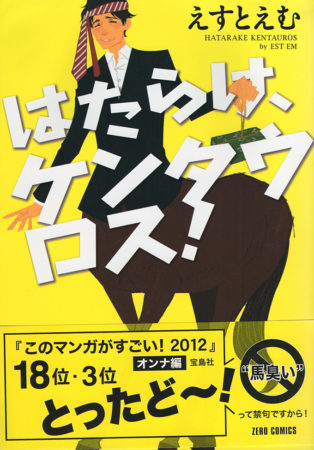

Four of the eight chapters in Hatarake, kentaurosu! prominently feature Kentarō (see Figure 1), a centaur who works as a salaryman at a horse tack manufacturer. From this premise alone, there are already multiple layers of parody. First, the irony and hint of masochism in a centaur working for a saddlery manufacturer is surely not lost on est em’s readers. In addition, Kentarō, a common male Japanese first name, also evokes the Greek word for centaur, from which the loanword kentaurosu’ derives. To the Japanese reader, Kentarō can also be read as a parody of Kintarō, a hero in vernacular narrative. Perhaps most famously, the Kintarō of traditional Japanese folklore is a sturdy young mountain boy who befriends animals, suggesting the blurring of the human/animal divide mirrored in the centaurs themselves.

Additionally, Kintarō may also evoke the titular Kintarō Yajima, protagonist of the massively popular seinen manga series Sarariiman Kintarō [Salaryman Kintarō’].8 The manga, which has been serialised on and off in Shūkan yangu janpu [Weekly Young Jump’] since 1994, follows former bōsōzoku (暴走族; motorcycle gang) leader Kintarō, who becomes a salaryman to raise his son after his wife passes away in childbirth. With only a junior high school education, Kintarō is hired by a construction company after saving the life of its CEO, and almost accidently goes on to become a successful businessman. Unlike Kentarō, who is a model for the traditional salaryman archetype aside from the fact that his lower body is a horse, Kintarō is in many ways its antithesis, embodying a hyper-masculine bravado and defiance that Ikuya Sato (1991) observes in bōsōzoku masculinity (69). However, by eventually conforming to the image of a respectable, urban salaryman by putting his company’s needs before his own, Kintarō comes to represent the synthesis of both the salaryman and the warrior, although Romit Dasgupta (2003) argues that ”this aggressively idealised figure … ends up as little more than a caricature” (128).

Both Kintarō and Kentarō’s work environments are nearly entirely comprised of men, harking back to Sedgwick’s continuum of homosocial desire. Kentarō’s friendship and interactions with his unnamed human co-worker, which is a focal point of many of the chapters, can easily be read as homoerotic by readers literate in BL manga. The emphasis on friendship between men is also a central theme of Osamu Dazai’s famous 1940 short story Hashire Merosu, which the title Hatarake, kentaurosu! likely evokes for Japanese readers. Based on the retelling of the Greek legend of Damon and Phintias in ”The Hostage” [1799] by German poet Friedrich Schiller, Hashire Merosu is included in many Japanese school curricula and popular collections of Dazai’s work. In the story, the shepherd Melos is enraged when he learns that the king Dionysus is killing citizens and even his own family members due to his distrust of others. Determined to put an end to his tyranny, Melos attempts to assassinate the king with a knife, but is quickly apprehended and sentenced to death. After pleading with the king to allow him to attend his younger sister’s wedding, Melos is released on the condition that he return within three days. In exchange for Melos’ release, the king takes his best friend Selinuntius hostage, and vows to execute him instead if Melos does not return before the deadline.

After attending his sister’s wedding, Melos journeys back to the king to fulfil his promise. Along the way, he is repeatedly thwarted by various obstacles, but hurries on in the hope of reaching Selinuntius before the execution. The story ends with Melos returning in the nick of time to embrace Selinuntius, an act of loyalty and friendship that moves the king so much that he revokes Melos’ sentence and asks to become friends with the two men. Translator James O’Brien (1989) notes in the English Dazai collection Crackling Mountain and Other Stories that many critics see the hero Melos as ”embodying ideas of trust, fidelity, and friendship” (111). However, O’Brien suggests that the story reads more as a ”mock-heroic” tale, with Melos depicted as a ”proud simpleton” rather than a hero. This is most evident in a scene at the end of the narrative where Melos is ”foolishly aware of his own nakedness” (1989, 111) for the first time, after running all the way back to the castle. Notably, this scene was absent from Schiller’s original poem and is removed from versions of Hashire Merosu distributed in schools, diminishing the comical element within Japan’s cultural narrative (1989, 111).

The deep friendship depicted between Melos and Selinuntius can also be identified as an example of nioi-kei (臭い系), a term used to identify texts that demonstrate a hint or whiff ‘ of BL to BL-literate readers (Aoyama 2012, 66). By combining nioi (臭い; scent) with kei (系), which is frequently used to designate subcategories in BL, fashion and other forms of contemporary popular culture, the term indicates to readers within the ”imagined BL community” (Aoyama 2012, 73) the potential for BL within the text, no matter how faint it may be. While Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro [1914] was ranked the number one ”nioi-kei literary masterpiece” in the February 2009 issue of book/manga review magazine Da Vinchi [Da Vinci’], Hashire Merosu was also selected for its nioi-kei properties by readers. Comments from two of the women polled were as follows:

Reading this as an elementary school student who didn’t know BL, I thought, ”These aren’t normal friends, are they?”[9「BL知らない小学生の時に読んで、「普通の友達じゃないよね?」と思いました。」] (female, office worker, 40)

They trust each other enough to risk their lives for one another, so it’s obvious

[that it’s BL].[10「互いのため命をかける信頼関係といったら、もう決まってる。」] (female, office worker, 40)

(Media Factory 2009, 28)

The first comment suggests that even at a young age, the reader sensed a more than friends’ connection between Melos and Selinuntius. As previously indicated, the text is included in many school curricula, which extol the deep friendship between the two men. However, in a dialogue in the same issue of Da Vinchi, BL novelist Natsuki Matsuoka and writer and BL enthusiast Shion Miura joke that the reasoning behind Melos attacking the king, or for Selinuntius to wait so diligently for his return, is ”full of [plot] holes” (すべてに穴がある) (Matsuoka and Miura 2009, 30). Rather than considering this a detriment to the narrative, they assert that it is the holes themselves that enable the BL nioi to seep through (2009, 30). Echoing the second reader comment, the two read the pair risking their lives for one another as love, rather than friendship. In the same way, BL-literate readers of Hatarake, kentaurosu! may also smell the nioi in the homosocial narrative, allowing the possibility for the relationship between Kentarō and his human colleague to be interpreted as implied BL.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE SALARYMAN

Through a nioi-kei reading, Hatarake, kentaurosu! invites female readers to imagine the possibility of male-male desire in the historically exclusive realm of salarymen. For many years, the salaryman, a model male employee and member of a heteronormative family unit, exemplified the hegemonic masculine ideal in Japan. According to Dasgupta (2013), ”typically the salaryman would be a middle-class, university-educated middle-aged man, with a dependent wife and children to support, working for an organisation offering such benefits as secure lifetime employment … and a promotions and salary scale linked to seniority” (1). Sociologist Raewyn Connell (1987) describes societal hegemony as ”a social ascendancy achieved in a play of social forces that extends beyond contests of brute force into the organisation of private life and cultural processes” (184). This ascendancy is ”achieved not so much through blatant domination and force, but rather in more subtle ways through interlaced ideologies and discourse circulating in society,” and is of particular relevance within the context of gender, and masculinity in particular (Dasgupta 2013, 7).

Due to Japan’s rapid economic growth from the 1950s, combined with the social normalisation of nuclear families and an increase in domestic consumer goods such as vacuum cleaners and refrigerators, the private/female and public/male binary continued in post-war society, helping to standardise the salaryman archetype (Uno 1993). Embodying ”loyalty, diligence, dedication, and self-sacrifice” (Dasgupta 2003, 123), the salaryman was not only required to perform well in the workplace but also conform to the requirements of hegemonic heterosexuality, such as marriage, children and financial provision for his family (Kelly 1993, 208—15). As Japan transformed into a late-capitalist society, however, welfare state conditions were pared back as the economy entered recession in the mid-1980s, and many middle-aged salarymen were retrenched (Dasgupta 2013, 130—31). By the late 1990s, Japan was in the middle of an economic meltdown. With economic stagnation, employers revoked conditions of lifetime employment and seniority-based remuneration. Employees felt betrayed by the corporations in which they had invested so much of their lives, and the masculine ideal of the main breadwinner that had continued throughout post-war Japan became less and less an achievable reality. In this socio-economic climate, the sōshokukei danshi (草食系男子; herbivore man’) emerged as an alternative to salaryman masculinity. Characterised as ”professionally unambitious, consumerist, and passive or uninterested in heterosexual romantic relationships” (Charlebois 2013, 89), these men are seen as ”less willing to take chances in their lives due to an anxiety-laden and unforeseeable future” (Suganuma 2015, 94).

Following the general erosion of the hegemonic salaryman masculinity as an obtainable ideal, Matanle et al. (2008) assert that ”salaryman manga offers a powerful cultural marker for urban Japanese males seeking to maintain their masculine self-identities within the confusion and insecurity of the contemporary Japanese business organisation” (645). While Sarariiman Kintarō”provides opportunities for salarymen to enact strategies for surviving and thriving under the pressures of working in contemporary Japanese business organisations” (Matanle et al. 2008, 660), Hatarake, kentaurosu! does not seek to instruct or motivate the modern salaryman. By targeting a female audience of BL-literate readers, it offers a critique of the compulsorily heterosexual, hegemonic masculinity of the corporate warrior. Instead of embodying the qualities of alternative sōshokukei danshi masculinity, however, Kentarō represents an ideal salaryman: he is well groomed, diligent and places his co- workers’ needs before his own. However, simply because Kentarō’s lower body is that of a horse rather than a human, it is impossible for him to represent the hegemonic ideal. This duality allows him to conform to certain aspects of hegemonic salaryman masculinity while remaining separated from others, much like female readers themselves.

Figure 1: KentarÅ on the cover of Hatarake, kentaurosu! © esutoemu 2011. Reproduced with permission.

The cover of Hatarake, kentaurosu! illustrates this juxtaposition by depicting Kentarō wearing a suit jacket with rosy cheeks and a tie around his head, signifying drunkenness. His bottom horse half is also clearly visible, forelegs twisted. The volume’s obi (帯), a slip of paper wrapped around the cover containing additional information about the text, reads ”don’t say horse smell’!” (“馬臭い”って禁句ですから!). While the scent of alcohol on Kentarō’s breath may be accepted as a rite of passage for an overworked businessman, remarking on the ”horse smell” of a centaur is considered offensive and embarrassing, exemplifying different codes of manners between humans and centaurs. The first page then features a colour illustration of the everyday necessities Kentarō carries in his bag and pockets. All are items that might be found in any salaryman’s briefcase, aside from a thick brush for the horse half of Kentarō’s body. This playful twist on a hair brush is a humourous inclusion for female readers who might carry something similar in their own bags. Representing the other while still embodying all of the traditional traits marking a model salaryman, Kentarō’s character parodies the closed male homosocial workplace for female readers in a fun and pleasurable manner.

PLEASURE AND PLAY IN EQUUS

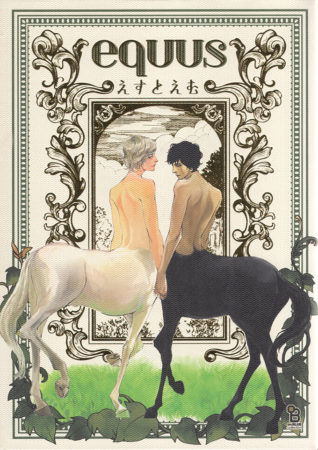

Unlike Hatarake, kentaurosu!, the stories in equus,9 with its two bishōnen (美少年; lit., beautiful boy’) centaurs on the cover (see Figure 2), are explicitly focused on romantic and sexual interactions. Named after the genus of mammals that includes horses and published in May 2011, equus is a collected work of short stories previously published by est em as dōjinshi (同人誌), which are non-commercial manga publications produced by amateur artists and manga fans, and usually distributed at conventions and other fan gatherings. equus was included as one of the top BL titles of 2011 in the annual book Kono BL ga yabai! (This BL is awesome!’), suggesting that est em’s male- male centaur eroticism resonated with BL readers (NEXT Henshūbu 2012). However, readers looking for the explicit erotic content prevalent in many BL may have been surprised to find the stories in equus to be more focused on emotion, rather than sexual gratification. est em herself has stated that the stories collected in equus consider how ”humans and centaurs affect one another” (人とケンタウロスがどう関わるか) (est em 2011a, 7).

In equus, each chapter is named after the coat colour of the centaur central to that chapter’s narrative. Aside from ”Dun Black,” which features a narrative spanning three chapters, each short story is a self-contained vignette. The relationships between man and centaur depicted in these stories are distinctly homoerotic in nature and tend to be much more serious than those contained in Hatarake, kentaurosu!. Rather than exclusively taking place in modern-day Japan, the settings of equus range from Europe to historical Japan. As Mark McLelland (2000) and others have observed, shōjo manga of the late 1960s and 1970s often featured exotic locations, allowing artists to explore themes such as male-male desire that would have been considered taboo in early postwar Japan (see also Prough 2010). This ”anti-realism” was established by setting narratives in locations outside of Japan, such as Europe or America (McLelland 2000, 18). In equus, the most sexually explicit chapters take place in undefined European locations, much like early shōnen ai manga such as Keiko Takemiya’s Kaze to ki no uta [The Song of Wind and Trees’; 1976]. Just like Takemiya, est em approaches the taboo subject of male-male centaur eroticism by setting the most explicitly homoerotic of these narratives in Europe, rather than Japan.

Figure 2: The cover of equus, with an ornate bishōnen aesthetic. © est em/Shodensha onBLUE comics. Reproduced with permission.

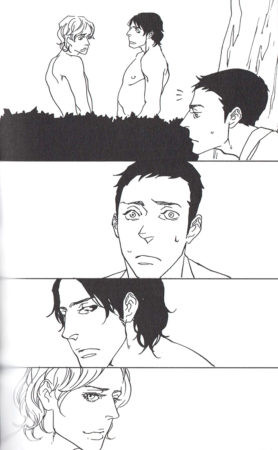

est em’s equus also shares its title with Peter Shaffer’s famous 1973 play, Equus. Set in England and inspired by a real incident, Shaffer’s play delves into the psychology behind a 17-year-old boy named Alan who blinds six horses in a horrific crime. The play is told from the perspective of the boy’s psychiatrist, an ageing, dissatisfied man who find himself enthralled by the boy’s intense spiritual commitment to his worship of horses. While this is not a preoccupation in est em’s stories, it is significant that she chose this title for her BL centaur collection, rather than the shōjo manga Hatarake, kentaurosu!. Significantly, Shaffer’s play deals with Alan’s sexual attraction to horses, particularly a male chestnut called Nugget. Alan’s intense worship of the horse god Equus culminates in him wishing to become one with a horse, which he achieves by riding Nugget naked and bareback in the dead of night. What is treated as abhorrent in Equus, however, is transformed into the comic/erotic in est em’s equus. In one short story, titled ”Chestnut,” a bareback riding scene similar to that featured in Equus transforms the one-sided intimacy Alan feels with Nugget to a mutual bonding romance. The ironic culmination of the young man mounting the centaur for the first time is not ecstasy, however, but an allusion to safe sex, where the centaur urges the rider to put on a helmet for safety (est em 2011b). In ”Black and White,” a human rider is bucked from his chestnut horse while riding through a forest (2011b, 35). Upon investigation, the man discovers that the horse was spooked by the presence of two naked men. However, it is quickly revealed that the men are not human, but rather centaur lovers. Fascinated by his first time seeing centaurs in the wild, the rider remains fixated on the pair as they kiss see (Figure 3). Noticing the staring rider, the centaurs playfully invite him to join them. The resulting centaur- man-centaur threesome can be read as an amusing twist on the ”strange” erotic fixation that Alan has with horses in Shaffer’s play. Instead of disgust and discomfort, est em’s sensual lines and wordless panels evoke a sense of longing, intimacy and eroticism between the man and the centaurs.

Figure 3: A human rider silently admires two centaur lovers in a forest, from equus. © est em/Shodensha onBLUE comics. Reproduced with permission.

Although est em’s focus is not on horses per se, the centaur men in est em’s manga derive from the half-human, half-horse hybrid familiar to Western culture. These centaur men are undoubtedly other,’ and face many of the same issues that real-word minorities such as gay men in Japan experience. They require separate traffic lanes to run in, their own bathrooms and modified dwellings. In Hatarake, kentaurosu!, centaurs have long coexisted with humans, but have only just been granted legal rights. Perhaps drawing from their liminal position between mortals and gods in Greek mythology, est em’s centaurs’ metabolisms are also significantly different from that of humans—not only do they require more food throughout the day to provide energy for their horse halves, but they also live for centuries, only reaching maturity at the age of 50. Perhaps an ironic commentary on Japan’s ageing society, Kentarō of Hatarake, kentaurosu! is already older than many of his superiors at work despite being a new hire, and will go on to outlive all of his human colleagues.

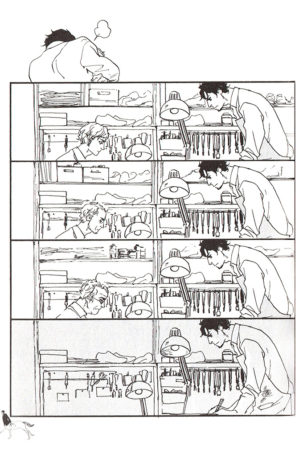

Age as a major difference between humans and centaurs is a recurring theme in both equus and Hatarake, kentaurosu!. In ”Dun Black,” a Japanese college student is shocked to learn that his centaur classmate has no idea how long his kind lives because he does not know anyone who has seen one die (est em 2011b, 5). In one of the more poignant stories in Hatarake, kentaurosu!, we see firsthand the impact that centaurs’ long lifespans have on their relationships with humans. A centaur who becomes a shoemaker due to his love of human shoes is shocked when he learns that his employer will leave his position once he is married. In a romantic comedy cliché, he bursts into the church to object to the marriage and proceeds to whisk his employer away on his back, saving him from a dull life with a woman he is not attracted to. Like Kentarō and his unnamed colleague, BL literate readers will undoubtedly view this pair as being intimately involved beyond their working relationship. As if lovingly depicting a couple growing old together, est em shows the human man ageing over the course of four panels until he is no longer present in the frame, while the centaur remains exactly the same (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: A four-panel depiction of the different rates of ageing between humans and centaurs, from Hatarake, kentaurosu!. © esutoemu 2011. Reproduced with permission.

Another story to focus heavily on the slowed centaur ageing process is ”Bay Silver,” which features a centaur slave who is passed down through three generations of human male owners over the course of three chapters. As his former master and lover lies on his deathbed, the always-youthful centaur agrees to look after the man’s son and is given a name for the first time in his life (est em 2011b, 111). This master/servant relationship that passes down from father to son is also a central theme of another BL manga, Shitsuji no bunzai [A Butler’s Place’; 2005] by Fumi Yoshinaga. In both Shitsuji no bunzai and ”Bay Silver,” the master/servant relationship becomes more intimate as the servant/slave is taught to read (Aoyama 2012, 74). Just as reading is a subversive act for the readers of equus, reading allows the characters of Shitsuji no bunzai and equus to break out of traditional social roles. Intimate scenes such as these also enable readers to better empathise with individual centaurs, and thus more acutely relate to the issues of alienation and inequality explored within these texts.

This focus on individual characters, while simultaneously highlighting the ways in which centaurs are both similar to and different from their human counterparts, is especially prominent in a chapter of Hatarake, kentaurosu! titled ”Moderu“ (モデル; model). In this story, an unnamed centaur model is fed up with his agency editing his photos so that no one will know he is a centaur (est em 2011c). When his latest ad campaign is unveiled, two fans can’t believe that he looks the same as he did over ten years ago, joking that he must be an android or heavily airbrushed. Humorously, the image has been edited, but not in the way they imagine. As a centaur, the model ages at a much slower pace than humans, so rather than his age, it is his physical difference that is being concealed from the public. In a minor but moving use of intertextuality, the model bitterly compares himself to the little mermaid who sacrifices her voice for a pair of human legs before finally quitting his agency. Soon afterward, however, the model is approached by a designer who wants to debut his new collection on the runway with a centaur. Focusing on original beauty,’ the collection highlights the model’s centaur form (see Figure 5), and the resulting advertising campaign inspires a new horseshoe trend among centaurs. While the themes of alienation and embracing one’s unique beauty present in this story are not unfamiliar concepts to readers, they are amplified through the use of centaur, rather than human, characters.

Figure 5: Centaurs admiring a beautiful centaur model, from Hatarake, kentaurosu!. © esutoemu 2011. Reproduced with permission.

CONCLUSION

Through the use of centaurs in equus and Hatarake, kentaurosu!, est em’s manga present subtle critiques of existing gender and social structures. Female readers are invited to enjoy the play of intertextual parody within these texts, while at the same time deconstructing the traditionally homosocial world of the salaryman and engaging with themes of otherness. The freedom to explore alternatives to hegemonic masculinity and patriarchal structures by which the readers themselves are bound may not enable immediate or lasting change. But even so, reading itself is a subversive act where anything is possible. As Aoyama notes, ”Rather than directly protesting patriarchal and heterosexist oppression, contemporary BL artists and readers seem to transform existing inequalities and potential threats into pleasure and gratification” (2012, 66). By referencing shared cultural motifs—from Sarariiman Kintarō to Hashire Merosu—est em encourages shōjo and BL readers to laugh at the intertextual pleasures of these male-dominated texts. Meanwhile, the male-male centaur romances in equus fulfil the desire for erotic BL narratives while also transforming the kind of one-sided devotion found in Peter Shaffer’s Equus into mutual, consensual pleasure. In doing so, est em’s centaur manga challenge existing constructs of normative heterosexuality and hegemonic masculinity while encouraging readers to enjoy the pleasures of homoerotic centaurs.

Disclaimer: The artist (est em) and the publisher of Hatarake, kentaurosu! (Libure

Shuppan) do not necessarily endorse the reading presented in this paper.

GLOSSARY

bishōnen (美少年)

lit., beautiful boy’; refers to the youthful beauty of adolescent boys and young men celebrated in Japanese culture as far back as the Heian period [794—1185]

BL

see boizu rabu

boizu rabu (ボイズラブ)

lit., boys’ love’; a genre of manga featuring male-male romance between adolescent boys/adult men marketed towards teenage and young adult women, often containing sexual content. Frequently shortened to BL’. This term is distinct from shōnen ai, which refers explicitly to male-male romance manga that was marketed towards teenage and young adult women during the late 1960s and 70s.

bōsōzoku (暴走族)

lit., speed tribe’; Japanese youth subculture associated with motorcycle customisation

dōjinshi (同人誌)

non-commercial manga publications produced by amateur artists and manga fans, usually distributed at conventions and other fan gatherings

dōseiai (同性愛)

lit., same-sex love’. This term came to replace nanshoku (同性愛; also read as danshoku‘, meaning male eros’) and shudō/wakashudō (衆道・若衆道; the way of the youth) during the Meiji period [1868—1912]

fujoshi (腐女子)

lit., ”rotten girl,”; originally used as an insult to denote women who read BL manga, now used by BL fans as both a playful and self-derisive descriptor

genpuku/genbuku (元服)

classical male coming-of-age ceremony

nanshoku/danshoku (男色)

lit., male eros’; used to describe male-male desire during the Edo period [1603—1868]. See also shudō/wakashudō

nioi-kei (臭い系)

comprised of the word nioi‘ (臭い; smell) and the colloquial suffix –kei‘ (系; kind/subgroup/type); used to identify texts that demonstrate a hint or whiff ‘ of BL to BL-literate readers

obi (帯)

lit., belt’, sash’; used in the publishing industry to denote the small paper wrappers on book and CD covers containing additional information about the contents

sashie (挿絵)

illustrations

seinen manga (青年漫画)

manga marketed towards young adult to adult men

shōjo manga (少女漫画)

manga marketed towards junior high and high school girls

shōjo shōsetsu (少女小説)

girls’ novels

shōnen ai (少年愛)

lit. ”boys’ love,”; refers to early male-male romance manga (circa late 1960s—70s) aimed at a female audience

shōnen manga (少年漫画)

manga marketed towards junior high and high school boys

sōshokukei danshi (草食系男子)

lit., herbivore man’; a colloquial term that refers to young adult men who are uninterested in professional advancement and heterosexual romantic relationships

shudō/wakashudō (衆道・若主導)

lit. ”way of the youth,” used to describe male-male desire during the Edo period [1603—1868]. See also nanshoku.

tankōbon (単行本)

an independent or standalone book (not part of a series). Manga tankōbon are often collections of chapters previously serialised in manga magazines

ukiyoe (浮世絵)

lit. pictures of the floating world’; woodblock prints that were popular during the Edo period [1603—1868]

REFERENCES

Aoyama, T. 1992. ”The Antinationalist Movement in Japan Circa 1910.” PhD Thesis. University of Queensland.

———— . 1994. ”The Love that Poisons: Japanese Parody and the New Literacy.” Japan Forum 6 (1): 35—46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555809408721499

———— . 2012. ”BL (Boys’ Love) Literacy: Subversion, Resuscitation, and Trans- formation of the (Father’s) Text.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal 43: 63—84. https://doi.org/10.1353/jwj.2013.0001

Aoyama, T. and B. Hartley. 2010. ”Introduction.” In Girl Reading Girl in Japan, edited by T. Aoyama and B. Hartley, 1—14. New York: Routledge.

Angles, J. 2011. Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishōnen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816669691.001.0001

Barthes, R. 1973. The Pleasure of the Text. Translated by R. Miller. New York: Hill and Wang.

Charlebois, J. 2013. ”Herbivore Masculinity as an Oppositional Form of Masculinity.” Culture, Society, & Masculinities 5 (1): 89—104. http://dx.doi.org/10.3149/CSM.0501.89

Cixous, H. 1976 [1975]. ”The Laugh of the Medusa” [La Rire de la Méduse]. Translated by K. Cohen and P. Cohen. Signs 1: 875—99. https://doi.org/10.1086/493306

Connell, R. W. 1987. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Dasgupta, R. 2003. ”The Salaryman’ and Masculinity in Japan.” In Asian Masculinities: The Meaning and Practice of Manhood in China and Japan, edited by K. Louie and M. Low, 118—34. London and New York: Routledge.

———— . 2013. Re-Reading the Salaryman in Japan: Crafting Masculinities. New York: Routledge.

Eagleton, T. 1983. Literary Theory: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

est em [えすとえむ]. 2011a. ”Anata no shiranai esu to emu“ [あなたの知らない えすとえむ] 2, Spring, 3—27. Tokyo: Shōdensha [祥伝社].

————. [えすとえむ]. 2011b. equus [エクウス]. Tokyo: Shōdensha [祥伝社].

————. [えすとえむ]. 2011c. Hatarake, kentaurosu! [はたらけ、ケンタウロス!]. Tokyo: Libure Shuppan [リブレ出版].

Fujimoto, Y. [藤本 由香里]. 1998. Watashi no ibasho wa doko ni aru no?: Shōjo manga ga utsusu kokoro no katachi [私の居場所はどこにあるの?:少女マンガが映す心のかたち]. Tokyo: Gakuyō Shobō [学陽書房]. https://doi.org/10.1353/mec.2012.0000

Fujimoto, Y. 2012. ”Takahashi Macoto: The Origin of Shōjo Manga Style.” Translated by M. Thorn. Mechademia 7: 24—55.

Honda, M. 2010. ”The Genealogy of Hirahira: Liminality and the Girl.” In Girl Reading Girl in Japan, edited by T. Aoyama and B. Hartley, 19—37. London and New York: Routledge.

Hutcheon, L. 1985. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. New York: Methuen, Inc.

————. 2006. A Theory of Adaptation. London and New York: Routledge.

Ishida, M. [石田 美紀]]. 2008. Hisoyaka na kyōiku ”yaoi/bÅizu rabu” zenshi [密やかな教育<やおいボイズラブ]. Tokyo: Rakuhoku Shuppan [洛北出版].

Ito, K. 2005. ”A History of Manga in the Context of Japanese Culture and Society.” The Journal of Popular Culture 38 (3): 456—75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.2005.00123.x

Kan, S. 2010. ”Everlasting Life, Everlasting Loneliness: The Genealogy of the Poe Clan.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal 38: 43—58.

Kaneda, J. [金田 淳子]. 2007. ”Yaoi ron, asu no tame ni (sono 2)” [やおい論、明日のため(その2)]. Yuriika [ユリーカ] 39 (16): 48—54.

Kelly, W. W. 1993. ”Finding a Place in Metropolitan Japan: Ideologies, Institutions, and Everyday Life.” In Postwar Japan as History, edited by A. Gordon, 189—216. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Matanle, P., L. McCann and D. Ashmore. 2008. ”Men Under Pressure: Representations of the Salaryman’ and his Organization in Japanese Manga.” Organization 15 (5): 639—64.

Matsuoka, N. and S. Miura. 2009. ”BL-nō de yomu meisaku bungaku annai“ [BL脳で読む名作文]. Da Vinchi [ダ・ヴィンチ] 178, February, 26—30.

McLelland, M. 2000. ”The Love Between Beautiful Boys’ in Japanese Women’s Comics.” Journal of Gender Studies 9 (1): 13—25.

McLelland, M. and J. Welker. 2015. ”An Introduction to Boys Love’ in Japan.” In Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan, edited by M. McLelland, K. Nagaike, K. Suganuma and J. Welker, 3—20. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press. https://doi.org/10.14325/mississippi/9781628461190.003.0001

Media Factory. 2009. ”Da Vinchi dokusha ga eranda nioi-kei meisaku bungaku besuto 3“ [ダ・ヴィンチ読者が選んだ臭い系名作文学ベスト3]. Da Vinchi [ダ・ヴィンチ] 178, February, 28.

Mizoguchi, A. 2010. ”Theorizing Comics/Manga as a Productive Forum: Yaoi and Beyond.” Comics Worlds and the World of Comics: Towards Scholarship on a Global Scale, edited by J. Berndt, 143—168. Kyoto: International Manga Research Center, Kyoto Seika University.

NEXT HenshÅ«bu [NEXT 編集部]. 2012. Kono BL ga yabai! 2012-nen fujoshi han [この BLがやばい!2012年腐女子版]. Tokyo: Ōzora Shuppan [宙出版].

O’Brien, J. 1989. ”Melos, Run!” In Crackling Mountain and Other Stories, edited by J. O’Brien, 110—126. North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- A bibliography of titles mentioned in this paper is provided as an Appendix. The bibliography includes titles and author names in Japanese script. English titles in italics are official translations, while those in single quotes are the author’s translations. ↩

- est em, a pen name, is a play on the Japanese pronunciation of S&M (エスとエム; esu to emu). She intentionally keeps her name uncapitalised in official publications. ↩

- Sentōru no nayami, Zeusu no tane, Ryū no gakkō wa yama no ue and Hatarake, kentaurosu! all take place in modern-day Japan or fantastical settings with cultural similarities to Japan. equus is comprised of numerous short stories that take place in both historical and modern Japan, as well as unnamed European locations. ↩

- This and other Japanese terms used are listed in a glossary at the end of this paper. ↩

- Such relationships share similarities with those between an adult man (erastes) and younger male (eromenos) prevalent in Ancient Greece (Reeve 2006, xxi). ↩

- Also read as genbuku’. ↩

- Kurofune ZERO is quarterly manga magazine by Libre Publishing that ran from 2008 to 2012, formerly known as Magajin ZERO (Magazine ZERO’). ”Kurofune,” or ”black ships,” refers to the Western vessels that arrived in Japan in the 16th and 19th centuries. Kurofune ZERO is now distributed as a free periodical on pixiv.net. BE∙BOY GOLD, another manga magazine produced by Libre Publishing, is referred to as a ”semi-monthly” magazine. ↩

- The commercial popularity of the Sarariiman Kintarō series can be demonstrated by its multiple adaptations: it has been made into a feature film (1999), video game (2000), live action television drama (2001), and an anime (2001). ↩

- The manga’s title is intentionally kept in lower case, perhaps to distinguish it from Peter Shaffer’s 1973 play, Equus. ↩