Re-Fashioning Kimono: How to Make Traditional’ Clothes for Postmodern Japan

Published June 20, 2015

Pages 59-84

https://doi.org/10.21159/nvjs.07.04

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney and Jenny Hall, 2015

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

New Voices

in Japanese Studies

Volume 7

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2015

Permalinks for references are available in the HTML version of this article.

Abstract

It is difficult to ride a bicycle or drive a car while wearing a kimono. Kimono are not considered suitable for contemporary life in Japan, and because of this, there is a pervading view that the Japanese traditional textile industry is in decline. However, Japanese designers and consumers are redefining Japanese clothing (wafuku) while retaining its traditional’ image. This project investigates how the contemporary reinvention of Japanese clothing embodies the process by which tradition and modernity interact, and helps us understand how new designs are a vehicle for designers’ and consumers’ expressions of Japanese culture.

Introduction

”You cannot ride a bicycle or drive a car while wearing a kimono.”

A Japanese apparel designer from Kyoto made this comment to me during an interview in 2010. After I repeated this statement at an academic conference on material culture, an American colleague contested this view, stating that she often wore kimono and rode a bicycle. This conflict of opinion illustrates how people from different cultures, and with different modes of engagement with Japanese culture, view the correct way to wear a kimono (as well as the correct way to ride a bicycle!). If a woman is wearing a kimono in the correct’ way—in the ”samurai-turned-bourgeois” style (Dalby 2001, 126) of post-war convention—it is difficult to do either of these activities. The tight tubular wrapping of the body means that large steps cannot be taken, and a leg cannot be thrown over a bicycle without dislodging the overlapping folds and the wide obi (the kimono waist sash). The obi, as knotted in a decorative style, would also become uncomfortable and crushed against the back of the seat of a car when wearing a seat belt. But whether or not activities such as cycling or driving are possible when wearing a kimono is not the issue. Rather, it is this perception of kimono that is significant. Why is it important? The designer’s statement above points to the heart of two simultaneous phenomena concerning the Japanese textile industry: firstly, the decline of wafuku (meaning Japanese clothes, including kimono); and secondly, its reinvention.

The term wafuku‘ is generally used as a counterpart to yōfuku‘, which was coined in the Meiji period [1868—1912] to denote Western dress (Dalby 2001, 67). As key scholar Dalby states, ”before yōfuku there could be no wafuku“ (2001, 66). The term wafuku‘ is usually used to refer to kimono, but can also encompass other forms of clothing worn throughout Japanese history, such as jinbei (a short jacket that crosses left-over-right with a tie fastening, and loose- fitting shorts or trousers), yukata (a lightweight summer kimono) and noragi (regional work clothing) that were typically comprised of two pieces: a haori (a short jacket), and mompe (loose fitting trousers that come in at the ankle). These forms of wafuku, which Dalby terms ”the other kimono”, are included in my analysis of contemporary clothing (2001, 161).

The overarching goal for my research is to understand how contemporary Kyoto designers and consumers are adapting and adopting wafuku, and how their new designs represent a vehicle for designers’ and consumers’ expressions of Japanese culture. Dress serves as ”the repository for conceptions of individual and collective identity” (Slade 2009, 4). It establishes the individual as a ”social being” (Lehmann 2000, 4) because dress communicates certain meanings about the wearer such as gender,1 status, class and social values. National dress communicates membership of a group at a state level, and states have used this to establish ”the mythical apparatus of a centralized nation-state” (Slade 2009, 14). The idea of ”Japaneseness” itself is a Meiji invention (Mathews 2000), and as noted above, wafuku came into being with this invention, placed as a binary opposite to Western clothing. The representation of kimono as national dress is what has defined the Kyoto heritage textile industries until recently, and consumption of kimono in the contemporary era has largely been connected to specific cultural uses.

The main research question for this article is: how are designers and consumers making kimono ride a bicycle’ in a figurative sense? In other words, how are they making wafuku suit contemporary everyday life? The re-creation of wafuku illustrates what is occurring at the nexus of the past and the present in the Japanese textile industry. In this paper, I contend that these two aspects challenge the pervading view that the Kyoto kimono industry is in decline. I analyse both the current situation of the kimono industry and the way that younger consumers’ engagement with kimono has changed, reinvigorating the position of wafuku. My fieldwork findings show that Kyoto designers and consumers are both redefining wafuku while retaining its traditional image and working to disconnect kimono from classical conventions and settings. In fact, the decline in kimono is being compensated for by a rise in revitalised Japanese clothing. Brumann’s (2010) comment regarding Japanese architecture can be equally applied to Japanese clothing: ”it is an ongoing connection of things past to the present, with the perspective of further evolution in the future, that is the motivational focus” of this revitalisation trend (162).

This interaction between the past and the present is accompanied by a complex negotiation of concepts such as tradition’ and authenticity’. These terms have been much debated in Japanese studies (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983; Vlastos 1998; Bestor 1989; Brumann and Cox 2010) and come packaged with value-laden assumptions that can, on closer examination, be challenged. For example, even though the kimono form dates back to the 10th century (Dalby 2001, 37), the contemporary mode of wearing it ”is an over-stylized invention of the Meiji period that has been transformed into a national symbol of Japanese culture” (Assman 2008, 371). Therefore, kimono as it is worn today can be viewed as an ”invented tradition” (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983). Traditional’ techniques used to produce kimono textiles, such as Nishijin ori (weaving)2 and Kyō-yūzen dyeing techniques, are not ”invented traditions” in that they are not recent in origin and therefore do ”establish continuity with a suitable historic past” (1983, 1). However, it is important to note that the Japanese notion of tradition simultaneously includes revitalisation (saisei) and evolution (Brumann 2010), which allows for development of new production techniques. Such evolution can be seen in contemporary Nishijin weaving and Kyō-yūzen dyeing (discussed later).

In this article, I adopt the fanciful image of the kimono riding a bicycle as a metaphor, where the kimono is symbolic of wafuku, and riding a bicycle’ is symbolic of suitability for contemporary lifestyles in Japan. I employ this metaphor in three ways. First, I apply it to the production of Japanese clothing in contemporary Kyoto, in the areas of manufacture and distribution. Second, I consider how Kyoto designers are creating contemporary apparel that is linked aesthetically to wafuku. Third, I look at changes in the consumption of kimono and wafuku, as well as how they are more generally viewed and interpreted by consumers.3 These changes are inextricably linked to concepts of national identity, because ”[f]rom the nineteenth century on, a single- mode kimono has been defined as native attire as opposed to the foreign or Western” (Goldstein-Gidoni 1999, 353). The links are either direct, through the representation of kimono as national dress, or indirect, through the creation of products that overlap symbolically or aesthetically with traditional apparel. Further, in both production and consumption (in this case, the act of donning and wearing), there is what can be perceived as a speeding up’ of kimono to make it more affordable and wearable. By considering both the production and consumption of dress, I aim to address the gulf that Entwistle (2000) claims has not yet been bridged between these arenas by social theory.4

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Data for this paper was collected during fieldwork in Kyoto in 2012, with follow-up communication in 2013 and 2014. Interviews were conducted in Japanese, and I spoke with contemporary Kyoto designers who use traditional methods and design elements to create contemporary fashion. To fully comprehend the designs and techniques these companies are using, the production side of the industry—namely, kimono- and obi-making—was also explored. Non-participatory direct observation, including video recording, was undertaken in order to document and obtain a deeper understanding of the working conditions of artisans and staff members. My fieldwork surveyed specific companies and workshops operating within Kyoto that were involved in producing kimono, obi or contemporary equivalents.

Due to my focus on the active use of the kimono, I wanted to think about the way that kimono is worn on the body, how garments are experienced as well as interpreted, and how this experience in turn affects production and consumption. I chose sensory ethnography as the methodology for the research because it refocuses ethnographic enquiry to include all of the senses in data collection methods and writing (Classen 1993; Howes 2003). For example, it encourages the researcher to be attentive to details such as how the tactile qualities of textiles affect the design process; the importance of visual observation for the transmission of tacit knowledge regarding heritage skills; and aural characteristics of workplace environments and their influence on the succession of skills. In addition, the textures of fabrics, the exact colours of a kimono, or the sound, rhythm and noise level of a power loom are easier to describe to a reader if they are experienced with all the senses.

Sensory ethnography can also give us information about kinaesthetic or bodily learning that language cannot. As such, it is a particularly good fit with the Japanese traditional arts because not only do many concentrate on and influence the sensory experience, but they are also taught through repeated patterns of movement known as kata, so that learning occurs through the physical reproduction of an action and relies on employment of all of the senses (Yano 2002, 24—25). Pink (2009) argues that the concept of an ”experiencing, knowing and emplaced [researcher’s] body is…central to the idea of a sensory ethnography” (25), and I contend that this is also the case in regard to the research subject’s body. The experience of both the researcher and the research subject informs and continually changes the meanings of objects. Howes aptly expresses this process when he says:

What gives objects their sensory meaning—and what may give them new meanings—is not just the memories we associate with them, but how we are experiencing them right now. Sensory signification is a continuing development, not a simple reliving of once-learned associations.

(2003, 71)

The sensory ethnographic research in this article contributes to the field of social anthropology by addressing the ”sensorial poverty” (Howes 2003, 1) in social anthropological discourse, ethnographic data collection methodology and anthropological literature.

INNOVATIONS IN TRADITIONAL CLOTHING-MAKING TECHNIQUES

Anecdotally, one might argue that Kyoto’s residents can be seen wearing kimono more often than residents in other major Japanese cities. Even in Kyoto, however, kimono is not considered typical everyday wear. It is primarily reserved for special occasions such as weddings, funerals, coming-of-age ceremonies and graduations, which means that demand is not consistent. Consequently, many in the kimono-making industry believe the industry is facing an unprecedented crisis, caused by factors including the current economic recession, lifestyle changes that have impacted on clothing styles, and the unwillingness of young people to learn traditional kimono- and obi– making skills (Hareven 2002; Moon 2013). Those currently working in the kimono industry are typically in their sixties or older and they cite the lack of successors as a main cause of the industry’s perceived decline (Yamada 2012; Kameda 2012). As Moon (2013) says of Nishijin weaving, ”many [in the industry] also claim that most of the craftsmanship will disappear when the present, aging generation retires” (79). Hareven also documents similar opinions (2002, 45).

However, there are signs of regeneration and revitalisation because of technological innovation and changing ideas regarding wafuku. There are currently three main traditional techniques being used in the Kyoto kimono industry that are recognised by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (hereafter, METI) as producing ”officially designated traditional craft products” (METI 2013): Nishijin weaving, kanoko shibori (fawn-spot tie-dyeing) and Kyō-yūzen (Kyoto-style paste-resist dyeing). This state recognition of Kyoto kimono techniques establishes them as worth preserving for the nation. These techniques are being retained through changes in technology and production processes that reduce costs and make the products more affordable.

Nishijin Weaving

Weaving is not only the construction of cloth but also the art of building patterns into fabric as it is woven on the loom (as opposed to patterns added later by dyeing, printing or stitching). Since the late Meiji period, much of the weaving performed in Kyoto has been not to make kimono cloth but to create obi (Nakaoka et al. 1988) and more recently neckties, bags and interior furnishings. However, the Nishijin Textile Industrial Association estimated that in 2011, 90% of Nishijin production was for obi, and only 10% was used for these other products (Nishijin Textile Industrial Association 2011, 1). The reason that Nishijin weaving is not used as much for contemporary apparel is complex. The work is labour-intensive and is divided minutely according to specialisation between family-run businesses (Hareven 2002, 110). For some manufacturers, production of certain goods is linked to their very identity, and this inhibits them from innovating. There is also a pervasive atmosphere of distrust and competitiveness in the industry that prevents the sharing of new ideas for goods (2002, 50). In addition, Nishijin goods are considered high-end goods, which pushes the price up and alienates potential customers (Moon 2013, 82).

Contemporary Nishijin manufacturers are attempting to revitalise the industry through technological innovation in the weaving process, at the design stage of production, and in distribution. There are four main types of loom in use in the kimono industry today: the treadle loom (a more traditional loom with no automation); the jacquard loom (a semi-automated system where a punch card controls the warp threads); the power loom (which uses a power source to drive mechanical parts); and the digital loom (computerised control of the warp and weft). All of these looms have the same function: to hold the warp threads in place while the weft threads are passed under or over them (Schoeser 2012, 169—70). The sequence of the warp-thread positions determines the texture and pattern.

Case Study: Shinji Yamada

Manufacturers started to use digital looms in the 1980s (Hareven 2002, 42) and this has enabled a reduction in production costs for obi. A digital loom is a power loom in which the jacquard design component has been computerised: the designs are transmitted to the power loom by computer, and the loom produces the design as dictated by the computer data. Shinji Yamada5 is a third-generation Nishijin-based obi manufacturer. Yamada produces mofuku obi (mourning obi) and more casual and colourful fukuro obi (a grade less formal than the most formal, maru obi) at his company. His company does not dye thread or fabric, but creates the designs and coordinates weavers in Tango Peninsula (in Kyoto Prefecture) to manufacture the obi.

Computer technology is enabling Yamada’s company to be more cost-efficient at the design stage of production (Yamada 2012). Designs are done in-house on a computer, and the digital blueprint chart is sent via email attachment. Yamada says that only 20% of manufacturers currently use this method; the other 80% outsource to a specialist, even though it is expensive (2012 He reveals that to outsource designs to an obi pattern designer would cost between JPY30,000 (AUD$300) and JPY50,000 (AUD$500) per design, but designing in-house using ”e-design” is ”free”—it just takes time (2012). His son, Nori, creates the designs for Yamada’s business using Photoshop, taking about five or six hours per design. So while the traditional obi manufacturers who outsource design are limited financially in the number of different designs they can produce6 Yamada can make hundreds of different designs (Figure 1). As the weavers Yamada employs use digital looms, the production time is much faster: about two to three days, as opposed to two to three months using traditional production processes (2012).7 Obi designs such as Yamada’s are primarily created through weaving, but designs for most kimono cloth in Kyoto are created through dyeing techniques like shibori.

Figure 1: Examples of Yamada’s fukuro obi. 8

Shibori

Shibori is the Japanese collective term for all forms of resist dyeing that use binding, stitching, folding, pleating, twisting, wrapping or clamping to create patterns across fabric. There are various kinds of shibori; for example, kumo (spider web) shibori, a pleated and bound resist technique; nui (stitched) shibori, which uses a simple running stitch pulled tight to gather the cloth; and itajime shibori, a shaped-resist technique created by sandwiching cloth between two pieces of wood. The most revered form of shibori in Japan is kanoko shibori (lit., fawn-spot tie-dyeing’) where the tiny tie-dyed dots are said to look like the spots on a fawn’s back (Tabata 2012; see Figure 2). It is the most difficult form of shibori because hundreds of tiny sections of cloth must be tied in rows, each one even and tight (2012). As the methods used to achieve each kind of shibori are quite different, artisans usually specialise. This means that several people could be involved in making one kimono depending on the techniques required for the design. Therefore, industry networks are vital for manufacturers, designers and artisans to connect and work together. Shibori manufacturers and artisans are changing traditional industry practices to make a kimono ride a bicycle’ in two ways: by using communications technology to inform manufacturers and consumers of their skills and products, and by outsourcing the time-intensive tying process to cheaper labour markets such as China.

Figure 2: An example of kanoko shibori by Kazuki Tabata.

Case Study: Kazuki Tabata

Kazuki Tabata creates a range of shibori in his home workshop in the southwest of Kyoto. His workroom is a typical tatami-matted room with a bench fixed to the end wall. The bench has hooks which are used to secure the thread for tying. Tabata learned shibori from watching his father and is now certified by METI as a traditional craft artisan. He dyes cloth using kanoko shibori (his main specialty) for traditional apparel like kimono and yukata, but he also works for contemporary apparel manufacturers such as design studio Sou Sou. The products he dyes for Sou Sou are noteworthy examples of wafuku designed for contemporary lifestyles. They include Sou Sou’s flying squirrel’ caplets, t-shirts, tenugui (cotton hand towels) and furoshiki (wrapping cloth) bags (Figure 3). He ties the fabric and dyes it by hand in his backyard (Tabata 2012).

Figure 3: A furoshiki bag dyed by Kazuki Tabata for Sou Sou.

Tabata has a blog where he displays images of his latest work and also has an online shop (Tabata Shibori 2015). As with the Nishijin weaving industry, artisans in Japanese textile industries have traditionally relied on established networks and family ties with designers, manufacturers and distributors. This affects the demand for their products as well as their acquisition of skills, as it is common practice in Japanese artisan families for potential successors to work outside the family to gain more skills and then bring them back to enrich the family business. The internet is helping artisans to sidestep these relationships, allowing exposure to different markets. In addition, by engaging with social media, artisans can assess the popularity of new products. Likes’ on Facebook and comments on his blog can give Tabata an indication of the items that might appeal to customers and therefore sell well (Tabata 2012). Furthermore, the internet provides industry visibility, which is vital for success—particularly given artisans’ high degree of specialisation. Tabata’s website gives his specialty as kanoko shibori, which allows manufacturers searching for this particular form of shibori to find him, and his METI certification gives him added legitimacy in the eyes of consumers (2012).

In contrast to this recent reliance on technology for communication, the actual craft of shibori is low-tech, physically demanding and labour-intensive. A sensory perspective gives an insight into some of the difficulties of Tabata’s craft, and suggests reasons as to why young Japanese are reluctant to take on shibori skills practice. Tabata mentions that the chemical dye smells unpleasant and that the dye vats attract mosquitoes, which sometimes makes his neighbours complain. In addition, for some techniques he has to use a mallet and bang to tighten thread, but he cannot do this late at night because it is too noisy. He also says that older artisans can no longer perform some of the techniques because they take a lot of strength and are physically demanding (2012).

Case Study: Kazuo Katayama

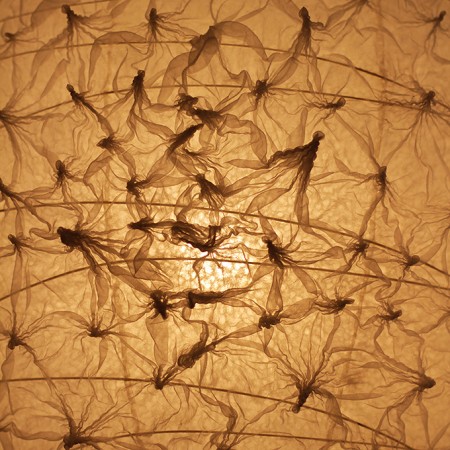

Kazuo Katayama is a shibori designer and manufacturer based in Kyoto. To address the problem of an aging artisan population and increasing production costs in Kyoto, Katayama sought an alternative to sourcing shibori artisans in Japan: he outsources to China (Katayama 2012). Katayama designs and sells shibori scarves and accessories with a very contemporary feel at his shop, Katayama BunzaburÅ ShÅten. He has been designing shibori for ten years but does not do any of the processes himself, apart from design. He outsources the tying to China, after which the items are shipped back to Kyoto for dyeing (2012). His adaptation of shibori exaggerates the tying aspect of the technique (Figure 4), resulting in three-dimensional sculptural works with unexpected applications (Figure 5). Katayama uses these sculptural characteristics to design scarves, necklaces, bracelets, lampshades and some clothing.

Figure 4: A shibori scarf by Kazuo Katayama.

Figure 5: A lampshade made from Kazuo Katayama’s shibori.

Yūzen

Beside shibori, the other primary method for dyeing kimono cloth in Kyoto is yūzen. Yūzen utilises paste-resist techniques with rice paste, either by piping the rice paste on by hand (tegaki yūzen) or by using stencils (kata yūzen) to apply it. It is much faster to dye a pattern onto fabric using kata yūzen than it is to weave a design, so production costs are cheaper than weaving. Traditional kimono-making companies such as Pagong Kamedatomi (hereafter Pagong, discussed below) have switched the use of their kata yūzen dyed fabrics (Figure 6) from kimono to contemporary apparel to overcome the decline in kimono sales. However, even kata yūzen is time-consuming, because if a design has twenty colours, then twenty dyes have to be mixed and twenty stencils made, with each one dyed separately.

A new form of yūzen has been invented in recent years that overcomes these obstacles: digital yūzen. Artisans can create their designs on a computer and print them out onto fabric using an inkjet printer. While these artisans still refer to their craft as yūzen‘, this method eliminates many of the time- consuming processes of traditional yūzen. Tegaki yūzen takes a minimum of ten steps and kata yūzen takes at least eight, whereas digital yūzen uses only six steps. But how can digitally printing a design using an inkjet printer still be called yūzen when it no longer involves most of the processes of yūzen? The answer is in part because of the Japanese framing of the concept of tradition: digital yūzen is merely a new innovation of yūzen production. Yūzen artisan Yūnosuke Kawabe explains: ”we think of tradition as a constant thing, as with our thinking about yūzen, but in fact it is always evolving and innovating”9 (Japan Style System Co. Ltd. 2015).

Figure 6: An example of Pagong’s kata yÅ«zen.

Case Study: Makoto Mori

Makoto Mori, a 26-year-old digital yūzen kimono maker, creates furisode, the long-sleeved formal kimono worn by unmarried women for the coming-of- age ceremony and other special occasions (Figure 7). His workspace is similar to a contemporary office, with computers and the constant hum of the inkjet printer. The visual similarity of his workplace and the prevalence of computer skills, both associated with the popular profession of graphic design, are more likely to be an enticement for young designers than traditional yūzen working conditions (Figure 8), which may involve working in draughty workshops, mixing batches of dye in buckets, and repeatedly humping large heavy stencils along banks of fabric. In addition, unlike traditional yūzen in which labour is highly divided, digital yūzen artisans are in complete control of their work.

Figure 7: Makoto Mori’s digital yūzen furisode [detail].

Figure 8: A traditional yūzen workshop; in this case, Pagong’s kata yūzen factory.

In summary, Kyoto textile artisans and manufacturers are applying a range of technological innovations and changes to their traditional production processes, from design through to distribution. These changes are enabling them to adapt wafuku for contemporary lifestyles by reducing production costs and thereby making items more affordable for consumers. Another way to make a kimono ride a bicycle’ on the production side is by producing more practical clothing for the present day.

CREATING APPAREL FOR CONTEMPORARY LIFESTYLES

Kyoto designers maintain traditional apparel using new materials or applying modern print designs to such items as kimono, haori or furoshiki; others retain the core elements of traditional clothing, such as kimono, and incorporate them into contemporary dress. At the beginning of this article, I recounted how a Kyoto designer noted the difficulty of riding a bicycle or driving a car while wearing a kimono. Shinji Yamada reinforces this point: ”you can’t do violent movements (激しい動きができないですよね)” in a kimono (Yamada 2012). He sees this both as a negative attribute, because contemporary life is fast-paced, and a positive one, because a kimono makes the wearer slow down and appreciate different things: ”When I wear a kimono and practice tea ceremony, my thinking slows down, I become calm (お茶する時、……考え方……着物きてしているとやっぱり丸くなるかな)” (2012). Despite the difficulties of wearing kimono and other forms of traditional clothing in modern-day life, some apparel producers continue to make them, albeit with a contemporary flair.

Case Study: Sou Sou

Sou Sou is a Kyoto design studio founded in 2002 by textile designer Katsuji Wakisaka,10 architect Hisanobu Tsujimura and apparel designer Takeshi Wakabayashi. Sou Sou creates wafuku by using new materials and applying modern print designs to traditional products, such as jika-tabi (split-toed shoes). They also create wafuku by using the main features of traditional apparel, such as long flowing lines, wide sleeves and attached neckbands that cross left over right, yet ensuring that the resulting clothing is more suitable for present-day lifestyles. An example is Sou Sou’s knitted cotton kimono- sleeved tops for men that feature wide sleeves and a v-shaped neckband that mimics that of a kimono (see Figure 11). Using these methods, Sou Sou strives to increase the relevance of traditional apparel to contemporary consumers.

One way that Sou Sou makes traditional clothing more relevant is through use of contemporary fabrics and patterns. Sou Sou produces a variety of traditional apparel and accessories made with its distinctive Katsuji Wakisaka-designed print fabric, such as asabura zori (straw sandals), furoshiki (wrapping cloth), tenugui (cotton hand towel), sensu (fan), hanten (short winter coat) and yukata (summer kimono). But their most popular traditional product is the jika–tabi: split-toed shoes with thin soles. Jika-tabi are traditionally a work shoe worn by farmers and jinrikisha pullers, and available only in black, white or indigo. They are purportedly good for balance, and historically have also been favoured by construction workers who have to traverse beams on site. Sou Sou’s versions (Figure 9) differ from traditional jika-tabi because they have a thicker sole for durability, as well as being made of more colourful contemporary fabrics and patterns. By reviving jika-tabi in this way, Sou Sou is attempting to change how this style of footwear is perceived in Japan.

Figure 9: Sou Sou’s jika-tabi.

There is some prejudice among older Japanese people about jika-tabi: when asked about the new-look jika-tabi, a group of Kansai women in their seventies still associate them with the lower working class and cannot understand why they are popular among young people.11 Sou Sou is changing this image by presenting work shoes as suitable for casual wear (much the same as occurred with American jeans), and the shoes act as a constant sensory reminder to the wearer of both the traditional and renegotiated meanings of jika-tabi. This exemplifies the dialectic between the past that ”lives on through the clothes and is revived in the details of sartorial styles created anew each season” and fashion’s constant quest for new meanings, because ”without the connotation of antiquity, modernity loses its raison d’ être“ (Lehmann 2000, 8). The Sou Sou designers maintain this link between traditional and new meanings by reproducing the main features of wafuku in their designs.

Retaining the Core Elements of Traditional Apparel

As mentioned, by adapting the features of the kimono to contemporary apparel, it can be said that designers are attempting to speed up’ the kimono to suit present-day lifestyles. This speeding up’ occurs at the donning stage— contemporary apparel is much easier and faster to put on—as well as in the wearing, because it allows for much more freedom of movement. While it might be straightforward to assume that adapted kimono forms are a hybrid of the kimono and Western clothing styles, Sou Sou’s clothing can also be interpreted as versions of the other kimono’—that is, other forms of wafuku that have been used for informal occasions for many centuries such as jinbei or noragi, as discussed earlier. In fact, Sou Sou describes its clothing as wafuku, and many designs reflect the shapes of traditional informal garments as well as items of Western clothing such as singlets, t-shirts, dresses, shorts and shirts. The influence of traditional clothing on Sou Sou’s designs is visibly evident, and is reaffirmed by product names: yukata-mitate dresses (dresses with features of the yukata), kataginu (sleeveless ceremonial robe for samurai), hirogata mompe (wide-legged mompe) and kyūchūsuso (imperial court cuffed trousers) (Sou Sou 2015). The figures below compare some of Sou Sou’s products with contemporary versions of historical costumes worn at the Jidai Matsuri (the Festival of Ages) in Kyoto (October 22, 2012), showing the influence of traditional clothing forms on Sou Sou designs. Sou Sou’s wafuku‘ challenges the traditional order of society by mixing imperial court styles with noragi (regional work clothing), demonstrating changing attitudes about fashion—much as with the new jika-tabi.

Figure 10: Jidai Matsuri participant wearing traditional trousers.

Figure 11: Kyūchūsuso (imperial court cuffed trousers) by Sou Sou (2015). © SOU SOU. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 12: Jidai Matsuri participant wearing traditional trousers with leg bindings.

Figure 13: Kyūchūsuso ayui (imperial court cuffed trousers with leg bindings) by Sou Sou (2015). © SOU SOU. Reproduced with permission.

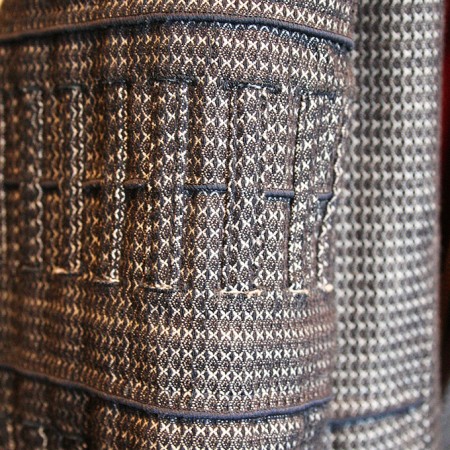

Case Study: Kyoto Denim

Kyoto Denim creates and sells jeans and other denim apparel in-store in Kyoto and online. The company’s yoroi jacket and jeans are another example of design that attempts to retain core elements of traditional apparel—in this case, samurai armour—and render it accessible to wider society. The jacket incorporates typical yoroi armour features (Figure 14), such as sections that mimic the kumihimo braid and plate-like shoulder guards (Figures 15 and 16), and the ribbed flaring collar that echoes the wide, semicircular neck guard of the helmet (Figure 17). The yoroi jeans have seven strips of denim on the outside of each leg that echo the traditional armour’s waist protector. The diamond patterns on either side of the hips (known as tasuki-kikubishi) are a traditional design from the Heian period [794—1185]. Designer Toyoaki Kuwayama says his aim in designing the jacket and jeans was to resurrect the chivalrous atmosphere of the Sengoku period [1467—1598]. Kuwayama is keen to ”combine Kyoto cultural virtue with foreign culture, technology and economics” (Kyoto Denim 2014). An emphasis on ”dynamism” and ”romanticism” are key marketing concepts for the products, which he labels a new form of ”wafuku“ (Kyoto Denim 2014). His interest in the evolution of Japanese attire is evident in his designs, and these designs in turn evolve further when the customer dons the apparel.

Figure 14: Jidai Matsuri participants wearing yoroi armour.

Figure 15: Kyoto Denim’s yoroi jacket.

Figure 16: Detail of Kyoto Denim’s yoroi jacket sleeve with braid.

Figure 17: Kyoto Denim’s yoroi jacket collar.

Contemporary Products from Traditionally Dyed or Printed Fabric

Judging by the number of retail outlets in Kyoto, contemporary apparel is by far the largest area of apparel production to use fabric decorated with traditional techniques, such as tegaki yūzen, kata yūzen and shibori. Dyeing techniques, in particular kata yūzen and shibori, are much more adaptable to contemporary garments than Nishijin weaving because more fabric can be produced in less time and at a lower cost.

Case Study: Pagong Kamedatomi

Pagong is the retail face of the Kamedatomi company, first established in 1919. The company originally dyed kimono fabric (woven elsewhere) for external kimono makers but now produces both men’s and women’s apparel. Pagong apparel is unique in its look because it is produced using kata yūzen and the motifs derive mainly from the company’s Taishō era [1912—1926] patterns. In the 1920s, the company commissioned nihonga (Japanese-style painting) artists to create the patterns (Pagong Kamedatomi Co. 2014). This era was renowned for its distinctive designs, sometimes called Taishō chic’, which employed a blend of modern and traditional elements. Third-generation owner Kazuaki Kameda comments on the suitability of his company’s products for present-day Japanese fashion:

I sometimes wished that our company had centuries of history like some Kyoto shops and companies, but if we hadn’t started in the Taishō era, we wouldn’t have our catalog of uniquely traditional and modern designs. Maybe people say that our catalog could not be more perfect for our current time, when people are longing for more connection to tradition and a by-gone world, our patterns in the shape of Western clothing does not look unnatural [sic]. (Pagong Kamedatomi Co. 2014)

By using original Taishō era kimono patterns, Pagong continues to reproduce an of that time’ style in their new designs. The Taishō era was a period of great transition in Japan, and Taishō design is distinguished by its ”balance between modernity and nostalgia” (Carr 2008, 2). It is important to note that at that time, modern’ usually meant Western, in contrast with traditional’ Japanese designs. Japanese artists of the time, such as Kiyoshi Kobayakawa [1899—1948], were influenced by Western art movements: ”Art Deco and Impressionism were a great inspiration for the Taishō artists who fused the elements of modernity and nostalgia to create a distinctive aesthetic” (Carr 2008, 2). On examining Pagong patterns, this influence is evident. For example, the pattern Asagao (Morning Glory), a design of red and yellow flowers with white and green leaves on a black ground from the early 1930s, is described by the company as ”high Art Deco”, with strong, colourful tints, an American flavour and a ”modern impression” (Pagong Kamedatomi Co. 2014).

When considering the original context of the company, the visual sensory picture becomes more complex. During the Taishō era, to wear a kimono was a statement in itself, as this was a time when women were starting to adopt Western-style dress. Modernity was associated with Western clothing in this era (Goldstein-Gidoni 1999), so to wear a kimono was a statement that could give a more conservative or patriotic impression. However, I surmise that to wear a kimono that was Western in pattern and colour could symbolise a more progressive outlook: I am both a modern woman and also Japanese’. It is also distinctly gendered, such that when women wear kimono they become ”a model of Japaneseness” (1999, 357).

In some respects, this is a reversal of what is happening today. During the Taishō era, the garment (kimono) indicated adherence to tradition, whereas the patterns printed on the fabric indicated a Western influence. Now, Pagong garments have a Western-style cut, but the printed patterns are considered traditional (Figure 18). Young women during the Taishō era were only just becoming accustomed to the feel of wearing Western-style clothes, whereas the young women wearing Pagong’s outfits are similarly not used to wearing kimono (young Japanese women today are often not able to dress themselves in a kimono without the help of a professional dresser). Kameda is not attempting to design garments that resemble the kimono, like Sou Sou does. Instead, he makes Western-style clothing using fabric printed with Taishō- era kimono patterns, combining traditional patterns with apparel suited to the contemporary lifestyle, and utilising traditional dyeing techniques to do it (Figure 19). The Pagong customers who wear these clothes embody the zeitgeist of nostalgic periods in Japanese history while renegotiating the original significance of the patterns, much like the wearers of Sou Sou’s jika- tabi. In this way, ”[f]ashion and modernity, as the expressions of elementary progress, need the past as (re)source and point of reference, only to plunder and transform it with an insatiable appetite for advance” (Lehmann 2000, 9).

Figure 18: Women’s tops [detail] by Pagong.

Figure 19: Contemporary apparel by Pagong.

DISCONNECTING KIMONO

Finally, a third way to make the kimono ride a bicycle’ is by disconnecting it from traditional social conventions and settings. The kimono’s image today is a garment that is beautiful but expensive, impractical, difficult to put on and daunting to wear in terms of adherence to the strict rules of etiquette that have developed since World War II. Yet the kimono industry and kimono wearers still persist because ”the kimono has become a communicative symbol to convey an individual attitude towards societal conventions and national identity” (Assman 2008, 360). The new efficiencies in production mentioned above would be meaningless if consumers were not interested in purchasing the apparel. These efficiencies enable individuals who once would only have been able to rent a kimono to purchase one; once purchased, they look for more opportunities to wear it outside the conventional occasions.

Individuals and retailers are challenging conventional ways of wearing kimono by making it less formal. This is taken to extremes via an increasing focus on asobi (play) and self-expression that is bringing the world of cosplay into the world of the kimono. This aspect of the consumption of kimono and wafuku demonstrates that ”[s]ocially, consuming is both a bonding and an individuating experience” (Stevens 2010, 202), and the concept of cosplay explicates this because by wearing both kimono and contemporary wafuku, cosplayers create and participate in a community. The term cosplay’ (kosupure‘ in Japanese) is an amalgamation of costume’ and play’, and usually refers to the practice of dressing in the clothing of a manga, anime, video game or movie character, and role-playing that character (Daliot-Bul 2009, 367). But more recent definitions are wider, with the important characteristics of cosplay being temporary transformation; the display of attire to an audience that can include the general public; and the asobi, or ”play” element, as opposed to wearing a uniform for work (Rahman et al 2012).

Case Study: Kimono Cosplay

Kimono Hime (lit., Kimono Princess’), a Japanese magazine published since 2003, instructs consumers in how to combine antique kimono and obi with modern Western accessories. Miki Aizawa, a stylist for Kimono Hime, mixes a kimono with tights and high heels, earmuffs, gloves and lace (Kimono Hime 2003), recalling the early Meiji period when, as Dalby notes, ”high button shoes, red flannel shirts, hats and capes—all worn with kimono—were thrown together into eclectic and exuberant outfits” (2001, 71). Aizawa has even included a front-tied obi such as courtesans used to wear in the Edo period—something bound to raise eyebrows among many kimono wearers because of this practice’s sexual connotations.12 Traditionally this was about practicalities concerning the wearer’s mizu shōbai (night entertainment business) profession, but today it is about making kimono accessible to younger wearers by introducing easier ways of adjusting and wearing them. In addition, this metaphorical loosening of the restrictive obi is about rendering kimono accessible to a wider range of wearers by changing the kimono’s image.

Kimono retailers and young Japanese are adopting these sartorial deviations. For example, Kimono Hearts is a chain of stores found in western Japan that rents kimono for various occasions. Their website categorises long-sleeved furisode kimono into the following styles: romantic girlie, glamorous, neo- classic, gothic, Japan trad’, floral feminine, Kyoto maiko13, oiran (courtesan) and retro trip, bringing cosplay noticeably closer to the realm of kimono (Kimono Hearts Corporation 2014). For example, the neo-classic style is described as being for those women desiring ”antique taste (アンティークなテイスト)” and suggests accessories such as pearls and lace. The gothic category is a ”mix of Japanese kimono and Western medieval styles (和の着物と洋の中世スタイルをMIXした)” with accessories that include gold and black ribbons, velvet and mesh. The oiran is described as ”Edo rock style (江戸のロックスタイル)” and features images of women wearing kimono off the shoulder and front-tied obi. Accessories include the tobacco pipe, takageta (tall wooden clogs), and wagasa (Japanese umbrella). Retro trip is a combination of ”Taishō romance and Shōwa [1926—1989] modern (大正ロマンスや昭和モダン)” that features kimono with either large flowers or hypnotic stripes in black, white, red, royal purple or cobalt blue, matched with equally bright obi in contrasting colours. Hairstyles are contemporary; bob cuts with bows and long cuts worn loose or in a chignon and decorated with floral clips. The practice of donning the elements of a particular category, and thereby acting out a role from a historical era or fantasy world, is extremely suggestive of cosplay.

While the cosplay world frequently involves kimono-wearing participants, these sartorial deviations are bringing cosplay into the kimono world. They expand the image of what can be cosplayed and indicate that cosplaying is now a pastime observed outside the manga/anime world. This increasing sense of playfulness around kimono has been enabled by the growing affordability of Kyoto’s digital yūzen, as well as second-hand and rental kimono. Kyoto rental and retail shop Guiches (2015) provides another example where kimono, accessories and hairstyles in marketing materials display a mix of traditional and contemporary. Osaka University of Arts students have taken some of these new styles on board, as illustrated by images of them dressed for their graduation in the magazine Untitle [sic] (2011). The students wear a mix of clothes, and none of the kimono wearers completely adhere to the conventional mode of kimono dress; for example, some wear boots or shoes as opposed to traditional footwear, while others adopt Western-style headwear. The elements of temporary transformation, play and performativity all apply to these situations, but ”unlike other simulation games’ during which a player temporarily plays a character of her/his choice, by adopting eccentric fashion styles a person plays himself or herself while constructing his or her personal and social identity” (Daliot-Bul 2009, 369). This aspect of the consumption of kimono and wafuku demonstrates that ”this is not just play’ but serious identity work that has consequences in other public arenas such as political and economic spheres” (Stevens 2010, 204)

CONCLUSION

This article has contested the viewpoint that the Kyoto textile industry is in decline. While it is true that many of my research subjects talked about the decline in demand for kimono in Japan, there is growth in traditional textiles being utilised in new designs. Looking at companies that are using traditional techniques to produce contemporary clothing, we can see that the industry is complex. Contributing factors include the invention of new products that employ heritage industry skills, innovations in production, new distribution patterns, and changing attitudes and tastes amongst consumers.

In all of these areas, there is a ‘speeding up’ of kimono in order to make it more compatible with contemporary life. Companies are reducing production costs to make wafuku more affordable. They are attempting to broaden the image of wafuku by creating products that link symbolically or aesthetically with traditional apparel, but offer functionality that is more optimal for contemporary lifestyles. Simultaneously, consumers are also attempting to change the image of kimono and wafuku, demonstrated by new wearing practices as well as the success of rental companies and magazines. A sensory perspective uncovers the reasons why individuals are reluctant to take up skills on the production side of the industry, and also why innovation is helping kimono ‘ride a bicycle’. Th e perceived decline in demand for kimono is not a question of the industry’s survival: the disconnection of kimono from classical conventions, as well as the focus on redefining wafuku, opens up new possibilities for garment design, thus allowing for new expressions of social and political identity.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- Much has been written about the issue of gender and kimono. While I acknowledge its importance, a thorough discussion of it is beyond the scope of this paper. ↩

- Nishijin is a district located in northwest Kyoto that is renowned for weaving. ↩

- I have also conducted research on marketing and how manufacturers and retailers use the discourse of tradition to sell their products, but discussion of that is beyond the scope of this paper. ↩

- Entwistle argues that the study of fashion usually fails to acknowledge the dual nature of the subject as both a cultural phenomenon and as an aspect of manufacturing, resulting in parallel histories of consumption and production (2000, 2). ↩

- A pseudonym has been used at the interviewee’s request. ↩

- In the past, it was even more expensive to get a pattern designed for an obi—about JPY100,000 (AUD$1,000) using traditional methods rather than a computer (Yamada 2012). ↩

- In addition to technological innovations at the design stage of production, Nishijin manufacturers have also been able to use new communications technology to their advantage at the distribution end of production. My research shows they have done this by putting their services online, making themselves more visible to retailers, and finding relevant retailers directly. They are able to bypass wholesalers if they wish as well as keep up with consumer trends. ↩

- All photos are by the author unless otherwise indicated. ↩

- 「伝統として変わらないモノと考えられがちな友禅も、実は絶えず進化と革新を遂げてきたのです。」 ↩

- Katsuji Wakisaka is well known in design circles for being the first Japanese designer to work for Marimekko, a Finnish textile company which had global success in the 1970s. ↩

- Personal communication with six members of the Sakura-kai study group, Osaka, April 21, 2010. ↩

- From the 17th century, courtesans and prostitutes became known for wearing their elaborately tied obi in the front rather than the back to assist with speedier disrobement and re-dressing (Dalby 2001). ↩

- Maiko are apprentice geisha. ↩