Romanticising Shinsengumi in Contemporary Japan

Published January, 2011

Pages 168-187

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21159/nv.04.08

New Voices

Volume 4

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2011

Permalinks for references are available in the HTML version of this article.

Abstract

Shinsengumi, a group of young men recruited by the Bakufu to protect Kyoto from radical Imperial House loyalists in the tumultuous Bakumatsu period, is romanticised and idolised in Japan despite its limited place in history. This article attempts to comprehend this phenomenon by locating the closest crystallisation of popularly imagined Shinsengumi in Moeyo ken, a popular historical fiction by Shiba Ryōtarō. Antonio Gramsci explains readers are attracted to popular literature because it reflects their philosophies of the age’, which may be discovered by examining popular heroes with their subsequent replications.

This article will identify why Shinsengumi is appealing by comparing Shiba’s hero in Moeyo ken with its twenty-first century reincarnation in Gintama, a popular manga series, and by discerning reader response to Moeyo ken from customer reviews on Amazon.co.jp. It will be demonstrated from these studies that a likely reason for the Japanese public’s romanticisation of Shinsengumi in recent years could be their attraction to autonomous, self-determining heroes who also appreciate the value of community.

Introduction

This article is an attempt to introduce and explain the widespread romanticisation and celebration of Shinsengumi, a previously unscrutinised, yet nevertheless fascinating social phenomenon in Japan.1 Shinsengumi was a group of young men recruited by the Bakufu to secure order and safety in Kyoto to counter terrorism staged by unruly jōi shishi (Imperial House loyalists). Their contribution to history is rather limited that at most, less than a page is allocated for them in history dictionaries such as the Great Dictionary of Japanese History.2 In short, not much is written about Shinsengumi other than their small victories and their anachronistic fate shared with the Bakufu’s downfall. However the group’s popularity is the inverse of their historical relevance.

For example, a quick search on Amazon.co.jp leads to 829 results just in the category of Japanese books.3 An unrestricted search further reveals widespread commercialisation beyond comprehension and imagination. Shinsengumi-related products range from conventional media such as novels, games, manga, films and dramas to quirky items such as figurines, accessories, pets’ costumes and even an idol group, Shinsengumi Lien. Their popularity is also noteworthy since their earliest appearance in popular media could be traced back to the 1920s.4 A critic of popular culture, Ozaki Hotsuki, notes that Shinsengumi’s popularity has also been consistent throughout history in contrast to the fluctuating popularity of other historical figures from the same period.5 Universality of their appeal is also suggested from their warm reception in other countries such as Taiwan and South Korea.6 These factors suggest fascination with Shinsengumi is neither a trendy fad nor a manifestation of Japanese people’s cultural penchant for tragic samurai.

Since historical accomplishments do not explain why Shinsengumi is romanticised and idolised, this article will discover why this particular group of young men continue to appeal to the Japanese public by looking at popular imaginations. First, it will be advanced that the characterisation of Shinsengumi in Moeyo ken (Blaze, My Sword)7, a taishū bungaku8 by Shiba Ryōtarō (1923-1996), is the closest crystallisation of popular romanticisation of the group. Then, the significance of taishū bungaku will be examined to demonstrate that a comparative study of popular fictional heroes and their replications could reveal the masses’ consciousness. On this basis, Shinsengumi’s popularity will be explained by comparing Shinsengumi in Moeyo ken and its replication in Gintama (Silver Soul),9 a manga series by Sorachi Hideaki, and by discerning reader response to Moeyo ken from customer reviews on Amazon.co.jp.

Locating Popular Imagination of Shinsengumi

No other text is more appropriate than Moeyo ken to extract the archetype imagination of Shinsengumi in post-war Japan. Firstly, the novel was voted as the best fictional representation of Shinsengumi in a 2003 magazine survey.10 Secondly, perception of Shiba’s Shinsengumi as a close reflection of the actual figures is such widespread that whether or not they decide to follow Shiba, post-Moeyo ken reproducers of Shinsengumi cannot ignore his rendition when formulating their own versions.11 Shiba’s influence must be considered in the context of his reputation as a prominent national writer.12 Being perceived as someone who can accurately communicate the realities of Japanese history rather than…a mere fiction- writer’,13 his characterisation of Shinsengumi transcends fictional boundaries and becomes a reality for many Japanese. In fact, one historian laments many texts place emphasis on Hijikata Toshizō, the vice commander of Shinsengumi, or Okita Sōji, the captain of the first unit, instead of Kondō Isami, the actual head of the organisation, because Shiba’s characterisations of Hijikata and Okita are overwhelmingly popular.14

Taishū bungaku as a Mirror for the Masses’ Philosophies of the Age

To comprehend why Shiba’s heroes are popular, this article will first examine the implications of Moeyo ken as a taishū bungaku. Originating from kōdan or historical romances for commoners, taishū bungaku is rather ambiguously distinguished from junbungaku (pure literature).15 It is argued that the term was initially adopted in the early 1920s to differentiate works from pure literature as well as from the more vulgar fiction.16 Thus labelling a work as taishū bungaku did not necessarily connote that it was non-serious or even commercially popular.17 Nevertheless, the two genres became qualitatively differentiated as authors of junbungaku were considered artists’ in contrast to their artisan’ counterparts.18 This division was further solidified with the creation of separate literary awards for each style.19 However in recent years, postwar economic expansion, development of mass media, writers’ shift from one genre to another and a new generation of writers’, such as Murakami Haruki’s, experiment with postmodernity have further challenged the definition of pure and popular.20

For our purposes, it is sufficient to note that authors of junbungaku wrote more for the sake of other writers’21 and were withdrawn from concerning themselves with political and national affairs’.22 In contrast, taishū bungaku has traditionally been absorbed and reflected by the masses through entertainment’.23 That is, popular literature exists precisely because the masses consider a work entertaining. Form, content and target audience of taishū bungaku have fluctuated across time as authors try to adapt to changes in the readers’ environment and perception. In this respect, readers are indirectly contributing to the creative process as writers attempt to meet the demands of their audience.24 Yet, the authors’ determination to entertain readers continues to be a key characteristic of the genre.25

According to Antonio Gramsci, entertainment in this context denotes more than amusement.26 Entertainment distilled in popular literature is an element of culture’ as it adheres to changes in the times, the cultural climate and personal idiosyncrasies’.27 These elements are produced through a careful calculation to make a novel successful by appealing to the moral and scientific philosophy of the age’: the deeply embedded feelings and conceptions of the world predominant among the ”silent” majority’.28 Heroes in popular literature are thus able to attract readers because their narratives reflect the masses’ ideals.

On this basis, it may be possible to locate a philosophy of the age’ by examining how and why readers are attracted to heroes of successful taishū bungaku. This requires a consideration of who constitutes as the silent majority’ in postwar Japan. Postwar taishū bungaku became more sophisticated and diversified as authors began to adopt a more realistic, informative or both styles of writing.29 Concurrently, its readership expanded from the existing readership of female readers and blue-colour workers, to include the emerging middle class, intelligentsia dissatisfied with the status quo and white-collar workers.30

Furthermore, in the age of economic expansion and commercialism of literature, writers of popular literature such as Shiba managed to appeal to some hundred thousands of readers’ by successfully distilling in their works values shared by the masses, or by at least giv[ing] the masses that impression’.31 Readership of taishū bungaku, or at least Shiba’s works, could therefore be described as a large group of people from various backgrounds, connected by their attraction to a work of fiction embodying their values. In other words, the silent majority’ could be considered as a reflection of the Japanese public.32

If the hero in Moeyo ken is our key to deciphering the masses’ consciousness, how do we identify the elements of entertainment distilled in him? This requires a scrutiny of how readers locate their own model heroes and compasses since the entertainment value of a work is ultimately judged by the audience.33 For this purpose, the practice of sequel-writers’ who revive’ and recreate’ heroes of successful popular fiction with new material’ is noteworthy since modifications are made to accommodate changing social sentiments.34 We may therefore discover why the masses are drawn to Shinsengumi by comparing Shiba’s heroes in Moeyo ken, the prototype of contemporary representations of Shinsengumi, with its reproductions. In turn, this could elucidate the underlying reason for popular romanticisation of Shinsengumi in contemporary Japan.

Scope of Study

For a practicable comparative study of Shiba’s Shinsengumi and its replications, the scope of this research will be defined as follows. Firstly, replication of Shiba’s Shinsengumi will be sourced from Gintama, a manga series currently being serialised by Sorachi Hideaki in Shūkan shōnen jampu (Weekly Boys Jump, hereafter Jump). Gintama is ideal because its Shinsengumi-based characters are heavily influenced by the author’s interpretation of Shiba’s heroes and the real Shinsengumi, as he claims, I love everything about the real Shinsengumi…ever since I read ”Burn, My Sword”. I just can’t get the original image out of my head’.35 The manga is also useful because in shaping the series, Sorachi and his editor are extremely sensitive to reader response collected from weekly surveys, sales data, fan letters and more.36 That is, character-making for Gintama involves negotiating images of Shinsengumi held by the author as well as the readers, with the author’s original input. In fact, Sorachi describes creating his own version of Hijikata Toshizō, the vice commander of Shinsengumi and the main protagonist of Moeyo ken, as destroying’ real Hijikata.37

Another reason for using Gintama lies in its fandom characterised by a strong female fan base38 and the male-oriented Jump readership claimed to encompass the under-tens to the over-sixties’.39 Coupled with the Jump manga production system which strongly values and responds to fans’ opinions, the nature of Gintama‘s fandom suggests the series is shaped to meet the demands of a relatively heterogeneous and large group of readers. Representations of Shinsengumi in Gintama could therefore be considered as a reflection of the group’s social images in the twenty-first century.

Secondly, a caveat must be imposed that in examining representations of Shinsengumi in Moeyo ken and Gintama, this article will consider the authors’ renditions of Hijikata Toshizō as reflecting the public’s perception of Shinsengumi as a whole. Not only is Hijikata the main protagonist of Moeyo ken and a major supporting character in Gintama, he also appears to be popularly appreciated as the epitome of Shinsengumi, the embodiment of its values and virtues. As noted previously, most Shinsengumi-related texts are focused on Hijikata, even though he is only the vice commander. The public’s adoration of Hijikata is also reflected in NHK’s broadcasting of Shinsengumi!! The Last Day of Hijikata Toshizō as a sequel to the taiga dorama (grand fleuve drama), Shinsengumi!’.40 As a particular genre of historical narrative that encourages and integrates present Japan by remembering and celebrating the past‘, taiga dorama influences, and is influenced by the zeitgeist of the Japanese society..41 Like heroes of popular fiction, popular taiga dorama heroes exhibit values which resonate with the Japanese public.

However, in the case of Shinsengumi!, it is arguable that NHK’s representation of Shinsengumi was insufficient to satisfy the public’s longings.42 The drama series was focused on Kondō, the head of Shinsengumi, and ended with his execution. Thereby Hijikata’s subsequent struggles against the new government were omitted from the series. However, viewers’ persistent demand forced NHK to eventually produce an unprecedented sequel about Hijikata’s final days in 2006, two years after the original taiga dorama was broadcast.43 This vignette reveals that Hijikata Toshizō is critical to complete popular romanticisation of Shinsengumi. Focusing our scrutiny onto Hijikata would therefore be more productive than canvassing different Shinsengumi members or reducing Shinsengumi into a single identity.

Amazon.co.jp Reviews as a Mirror for Popular Perception

To confirm whether the metamorphosis of Toshizō into Tōshirō corresponds to contemporary readers’ imagination of Hijikata Toshizō, customer reviews of Moeyo ken on Amazon.co.jp will be examined, since the reviewers tend to equate Shiba’s protagonist with the actual historical figure.44 These reviews are not quantitatively and qualitatively sufficient to draw a comprehensive ethnography of the fandom; only 152 reviews were published in the period from late 2000 to August 2009, and the reviewers remain anonymous. But the reviews are nonetheless useful to grasp a preliminary understanding of how readers imagine Hijikata because the time of publication is close or corresponding to the period when Tōshirō of Gintama is being produced. Also, anonymity of private criticism such as Amazon.co.jp reviews allows reviewers to express frank opinions. Ann Steiner notes that private criticisms commonly feature personal interpretation or experience of a text’, expressions of frequently heightened emotion’, the degree of which is relative to the degree of anonymity, and self-expression/ self-exposition.45 That is, Amazon.co.jp reviews display readers’ intimate interpretations and experiences about Hijikata Toshizō. Therefore, a scrutiny of these reviews could reveal the readers’ perceptions of the hero.

Toshizō: an Archetype of Real Japanese Men

Before we probe the readers, let us first consider the hero of Moeyo ken, Hijikata Toshizō (1835~1869), who will be referred to as Toshizō to distinguish the fictional character from the actual person or other versions. He is another archetype of Japanese men idealised by Shiba, whose view of male aesthetics concedes that a real man dies for his risei to kigai (reason and spirits) as opposed to ideologies and discourses’.46

Toshizō’s reason and spirits lie in the determination to accomplish his aesthetics as a kenkashi, a fighter, rather than the more sophisticated and chivalrous samurai or shishi. The protagonist moves from the outskirts of Tokyo to Kyoto in response to the Bakufu’s recruitment of the shogun’s bodyguards. Together with his friends, Toshizō soon becomes the backbone of Shinsengumi, a Bakufu protection squad consisting of men from various classes and walks of life.

Having appointed himself as the vice commander, Toshizō successfully disciplines and organises the group into a powerful military corps by adopting makoto (sincerity) as trademark and adopting Kyokuchū hatto, a strict code of conduct attracting seppuku if violated. Such stern determination and ruthlessness award Toshizō with notoriety as the demonic vice commander among residents of Kyoto and his enemies. Concurrently, Shinsengumi’s reputation also peaks with a successful raid on a secret jōi shishi meeting at the Ikedaya Inn.

But their glories are short-lived as Shinsengumi descends alongside the Bakufu’s downfall. Kondō’s execution is ordered by the new government and many core members also perish in battles. Nonetheless, Toshizō and remaining members continue to fight against the forces of the Meiji Restoration and even join the movement to establish the Republic of Ezo in Hokkaido.

Toshizō, now the republic’s deputy minister for military, continues to be driven by his aesthetics as a fighter. Contrary to other ministers seeking to surrender to the new government, he charges out for the last time to fight his enemy. When an opponent soldier demands his identity, Toshizō, after deliberating for a moment, declares himself as not the deputy minister of the Ezo Republic, but as the vice commander of Shinsengumi. The stunned soldier questions Toshizō’s intention, only to become further baffled when our hero proclaims, I believe I have already stated my agenda. If the vice commander of Shinsengumi has a reason to visit the opponent’s Council of War, it is because he seeks to slash the members of the Council’.47 These become Toshizō’s last words as he falls from the soldier’s gunshots. Thus an end comes to the tumultuous fate of Toshizō and Shinsengumi, and to their fleeting yet blazing appearance in Bakumatsu Japan.

As a text, Moeyo ken is open to numerous interpretations. To readers familiar with classic Japanese tragic heroes such as Minamoto no Yoshitsune, Toshizō may appear as another noble, but failed hero.48 On the other hand, the close intertwining of Toshizō’s life with Bakumatsu history may inspire others to read it as a nationalist discourse about an ambitious, youthful hero whose life merged with the making of the Japanese nation like Sakamoto Ryōma.49 That is, Shinsengumi as depicted by Shiba could be tragic heroes, exemplary Japanese citizens, charismatic individuals, all at once or none of these. Although interesting, these interpretations do not explain Shinsengumi’s popularity as they are no more than fragmented speculations, void of voices of the actual fans who appropriate popular texts and reread them in a fashion that serves different interests’.50 Discovering why this particular characterisation of Hijikata Toshizō is admired necessitates an inquiry into popular perception.

Tōshirō: a Reincarnation of Hijikata Toshizō in the Twenty-First Century

Recalling that popular heroes of taishū bungaku become revived with revisions to meet changing social sentiments, this section will introduce the twenty-first century reincarnation of Hijikata in Gintama. Sorachi presents his interpretation of the popular hero by transporting Shinsengumi into a science-fiction, periodical comedy set in the fictional city of Edo, a mix of actual Edo from the Bakumatsu period and present Tokyo. In the manga series, gaijin (foreigners) are replaced with Amanto, extra-terrestrial aliens who invaded the land of samurai and subdued the Bakufu into their puppet. Amanto technology has transformed Edo into a hybrid of old and new; people still wear kimono, albeit in modified forms, but become hyped over the latest game console, Owee.51 Like their real counterpart, samurai in Gintama are prohibited from bearing swords in public and thereby, effectively deprived of their once-honourable warrior status. Gintoki, the main protagonist and a jōi shishi-turned jack of all trades, is not afraid to challenge the currents of his time as he continues to carry a wooden sword. Together with his assistants, Gintoki pursues his way of the soul while working as Odd Jobs Gin’ in the downtown area of Kabuki-cho.

In the course of their work, the Odd Jobs gang encounter many colourful residents of Edo ranging from Mademoiselle Saigō Tokumori, an ex-jōi shishi gay club manager, to the Shogun, Tokugawa Shigeshige.52 These characters typify Sorachi’s parodying of reality in Gintama as they are similar, but not identical, to the actual historical figures. Shinsengumi is likewise reincarnated with a different kanji name as Edo police force. With Hijikata Tōshirō (hereafter Tōshirō) as the ruthless vice commander, Shinsengumi joins Gintoki’s adventures on many occasions. Material aspects of Sorachi’s Shinsengumi drastically differ from those of Shiba’s Shinsengumi; Tōshirō and his company ride patrol cars and use firearms such as bazookas in addition to their prized swords. Yet when it comes to personalities, Sorachi’s Tōshirō is quite close to Shiba’s Toshizō.

A Comparative Reading of Toshizō and Tōshirō

The most notable similarity in both renditions of Hijikata is their strong, almost- irrational determination to pursue personal objectives. Sorachi’s Tōshirō is unconcerned about the interests of the Bakufu or the Japanese nation despite his position as the vice commander of a police force. Rather, he is focused solely on the interests of Shinsengumi which he and his friends such as Kondō, the chief commander, established with their bare hands. Tōshirō’s dedication to Shinsengumi is akin to an obsession that when Kondō, the figurehead of Shinsengumi, loses comically in a trivial fight, the vice commander bellows in fury, we created Shinsengumi with nothing but our swords. I won’t let anyone ruin our Shinsengumi. Should there be anyone in my way, I will simply slash them with my sword!!’.53

The nature of Tōshirō’s attachment to Shinsengumi is revealed in an episode where the Bakufu orders Shinsengumi to protect a corrupt Amanto official from jōi terrorists. When his subordinates complain about the irony inherent in police protecting the Amanto official who is technically a criminal, Tōshirō simply responds Shinsengumi are not Bakufu subjects. He asserts Shinsengumi are subordinate to none other than the head of Shinsengumi, Kondō, who provided a place of belonging for them, uneducated rogues who knew nothing but how to swing a sword’.54 Having self-analysed his capacities, limitations and circumstances, Tōshirō is aware that his sole talent in fighting could only be realised through Shinsengumi in times when sword-bearing is forbidden. He thus acknowledges Shinsengumi as being pivotal to his self and dedicates his life to protect it. The vice commander further explains to his men that as the head of Shinsengumi’s kindness will not let him ignore anyone or even an Amanto alien in danger, Shinsengumi will gladly accede to his will and save the alien. Sorachi’s character is unconcerned about the illogicality of his actions as long as it suits his logic that Shinsengumi, their home, is preserved by ensuring the head’s authority and integrity are upheld.

Shiba’s Toshizō is likewise strongly aware of his fighting and leadership abilities. Accordingly, he is determined to achieve self-actualisation by fostering Shinsengumi, a motley rabble of men from various walks of life, into a samurai organisation more stoic and authentic than real samurai. Thus when Toshizō is questioned whether his intention to strengthen and expand Shinsengumi stems from a desire to gain the status of a daimyō, a samurai lord, Toshizō strongly refutes the suggestion:

Of course I don’t wanna become one. Would Toshizō, the rebel…, be able to fill the shoes of a daimyō?…I’m a craftsman. Not a man of noble spirits or anyone else. I even try not to think about the current state of affairs. I just wanna build Shinsengumi into the best group of fighters in the world. I know my limits.55

Toshizō’s stern determination to practise his aesthetics of life as a fighter is also vividly illustrated in his anachronistic, futile fights against the new government resulting in death. It is important to note that he is aware of the drastic changes to his surroundings and the irrationality of his actions as his efforts will only result in adverse outcomes. Nonetheless, his self-determination as a Shinsengumi fighter is not swayed by these factors. Rather, it could be argued that Toshizō willingly advances to his death at the enemies’ hands because dying in combat as the Shinsengumi vice commander completes his self-actualisation. In short, Shiba’s ideal hero is a man whose personal philosophy defies worldly logic and rationality.

The twenty-first century reincarnation of Hijikata in Gintama displays the same degree of dedication to personal aesthetics in The Tale of Disturbance within Shinsengumi’, a story arc where Shinsengumi’s solidarity is threatened by Itō Kamotarō’s coup d’état.56 The excerpt begins with Tōshirō becoming possessed by Muramasha, a demoniac sword cursed by the spirit of a hikikomori otaku, which turns the vice commander into Tosshi, a hopeless otaku sapped of willingness to work.57 Tosshi is soon fired from Shinsengumi for the new persona forces him to break the very code he imposed on Shinsengumi. Concurrently, Itō attempts to take over the organisation by assassinating Kondō. But his plan becomes troubled as Shinsengumi fiercely resist to serving an empty person who has neither samurai ethics nor integrity’.58 In order to save his friends, Tosshi breaks the spell of Muramasha and returns to his original self in a dramatic exposition spanning across two episodes:

Mr Kondō, we assigned you with a duty in return for our life at your service. That…you must not die…you have to survive…

Because Shinsengumi will not perish so long as you continue to exist, because we joined Shinsengumi for we admire you…

Kondō, you’re the soul of Shinsengumi and we’re the sword that protects it.59

The vice commander continues in a manner reminiscent of Toshizō’s final moments in Moeyo ken,

If you want Kondō’s head, you’ve gotta beat me first. No one can pass through me.

No one can ruin our soul.

I’m the last fortress protecting Kondō, the last sword protecting Shinsengumi.

I’m Hijikata Tōshirō, the vice commander of Shinsengumi!!)60

Tōshirō eagerly stakes his life to fight for Shinsengumi, the crystallisation of his life. Like Shiba’s hero who even welcomed death to advance his aesthetics as a fighter, Sorachi’s twenty-first century rendition of Hijikata is not afraid of fatal dangers inherent in his pursuit of personal aesthetics.

Sorachi’s characterisation of Hijikata as a self-driven individual is also reflected in Gintama‘s main character, Gintoki, who is described by the author as a shattered’ version of the original image, i.e. real…Hijikata’ stripped of the hero-image’.61 In the same story arc, Gintoki sides with Hijikata to protect Kondō and Shinsengumi despite his past as a jōi shishi. During the fight, an opponent ridicules Gintoki’s action as a futile effort to protect a grotesque, rotten country that has been devoured by the Amanto’ and advises him to instead revolutionise Edo like a proper jōi shishi.62 Gintoki refutes by correcting his opponent’s misunderstanding of the nature of his battle:

Not once did I fight for this cheap country.

Whether this country or the samurai comes to an end — I don’t care. I’ve never cared about it from the beginning.

What I was protecting before, and continue to protect today hasn’t changed one bit!!63

These words are accompanied by a collage of the protagonist’s friends, including Shinsengumi.64 Here, an overlap of Gintoki’s and Tōshirō’s personalities could be observed as they both value personal kinships and consider this aspect of their personality as a guiding principle of life. Being another reincarnation of Toshizō, Gintoki is determined to live according to his ideals whether or not he is right.

Analysis

Until the end, Hijikata Toshizō in Moeyo ken is driven by a personal determination to actualise his talent in fighting through Shinsengumi. Similarly, the life of Gintama‘s Hijikata Tōshirō, the twenty-first century reincarnation of Shiba’s Toshizō, is driven by his determination to protect Shinsengumi. The reasons for their attachment to Shinsengumi differs slightly as Toshizō is concerned more with self-actualisation as Shinsengumi in contrast to Tōshirō, who identifies Shinsengumi as his sanctuary. However, both characters share a common attribute; their determinations are unswayed by any external influences such as changes in the political climate or in their personal circumstances. Turn of fate expels Toshizō from the status of an honoured and feared Tokugawa samurai and turns him into the enemy of the emperor and state. It also forces Tōshirō to break the very code he imposed on Shinsengumi and thereby robs his standing as the vice commander. But both characters are not dispirited by these changes; Toshizō continues to fight as Shinsengumi to his very death even though the organisation has lost all legitimacy and Tōshirō continues to fight for Shinsengumi’s survival even though he has been dishonourably discharged from the force against his will.

In short, Toshizō and Tōshirō are strong and single-minded heroes who are dictated by none other than themselves. Moreover, they both have the strength to pursue their personal philosophies about life against thecurrents ofthe times. Viewed in this light, they could be described as autonomous, self-determining heroes. Self-determination theory contends humans are naturally growth-oriented beings who attempt to master and integrate their experiences into a coherent sense of self ‘.65 Individuals are inclined to exercise autonomy, i.e. to regulat[e] one’s own behaviour and experience, and gover[n] the initiation and direction of action’.66 This trait could be found in both renditions of Hijikata as the character’s selves form the centre of initiation and agency for their actions. In Tōshirō’s case, his attachment to Kondō and Shinsengumi does not diminish his autonomy because his reliance on them is an act of volition flowing from his own assessment of his self and surroundings. In short, both characters are driven by their personal aesthetics, which are based on a strong awareness of their selves.

There is nearly forty years of time difference between Moeyo ken and Gintama. During this period, Japan and her people have experienced dramatic changes as the golden period of rapid economic expansion gave way to the bust of economic bubble, and subsequently to the Lost Decades. In light of these changes in society, it is highly noteworthy that Toshizō’s almost-reckless drive to accomplish his aesthetics continues to be a defining characteristic of the twenty-first century remake of Hijikata, Tōshirō. Indeed, time has not failed to mark a difference between the two versions. Tōshirō exhibits attachment to Shinsengumi as a community of comrades and considers himself as the living shield for Shinsengumi. In contrast, Toshizō considers himself as the living embodiment of Shinsengumi. Nonetheless, these characters demonstrate that modern- day consumers continue to romanticise Hijikata Toshizō as a self-determining individual who is equipped with the fortitude required to pursue one’s ideals in harsh times of reality.

Readers’ Imaginations of Hijikata Toshizō

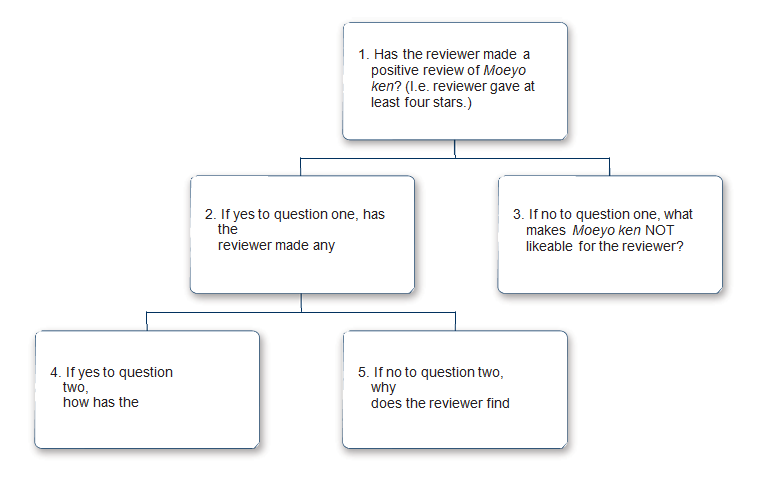

To establish a stronger connection between the popular romanticisation of Hijikata identified from the comparative study and the masses, this section will present readers’ perceptions of Hijikata manifest in Amazon.co.jp reviews of Moeyo ken. Reviews have been screened to eliminate multiple or unrelated entries and processed through a set of questions three times to create a circular and continually adaptive’67 flowchart. That is, results from first and second observations were used to identify recurring themes and to re-design questions and response categories. Responses to question four are most relevant as they relate to the readers’ construction of Hijikata.

Figure 1 – Flowchart of Questions

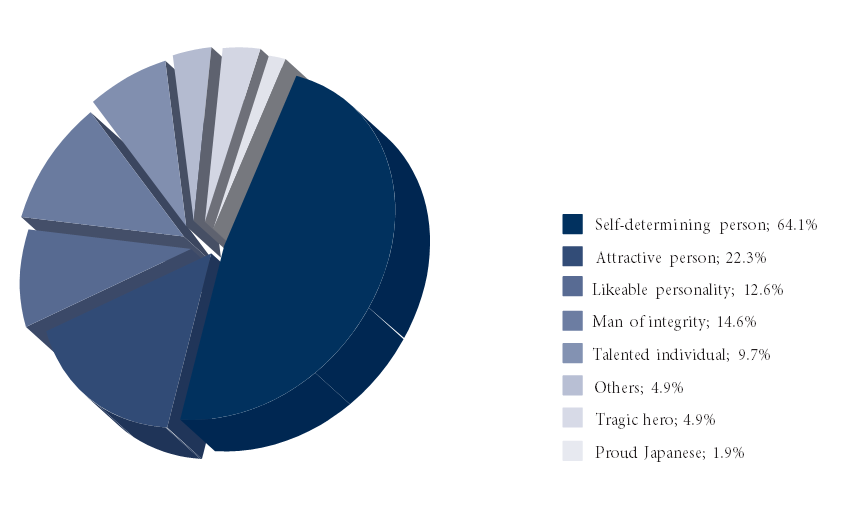

Out of 152 reviewers identified, 149 uploaded positive reviews as only three awarded Moeyo ken three stars or less, and 103 reviewers commented on Hijikata’s characteristics. At the end of the third stage of analysis, readers’ views of Hijikata could be categorised as follows: a) a tragic hero, b) someone who makes the reader proud of being Japanese, c) a self-determining individual, d) an attractive individual because he is kakkoii (cool), heroic or antiheroic without further elaboration of these descriptions, e) a person with a likeable personality (e.g. being humane, empathetic, down-to-earth and/or straightforward), f) a man of integrity, g) a talented individual, and h) others. The first three response categories were adopted to check if a response corresponds to likely approaches to reading Moeyo ken previously canvassed in the article. The latter were established after two counts of review analysis to make a coherent synthesis of the responses.

Figure 2 – Graph of Amazon.co.jp Review Analysis

Strikingly, 64 per cent of reviewers described Hijikata as a self-determining person. Considering they could have characterised him in any manner, the majority’s identification of Hijikata as a self-driven individual indicates reviewers consider this characteristic as his defining feature. A reviewer, Sūjī, quotes Toshizō’s words as his or her own philosophy on life:

To Live

”The times are not a matter of concern. Victory and defeat also need not be discussed. A man must follow his envisioned aesthetics to the grave”.

The words Hijikata Toshizō cast on Kondō Isami, words which also continue to torment me.68

Many readers appear to agree as 21 out of 23 users rated this review as useful. Others also similarly note that they view Hijikata’s life as a compass for life’, or that they could re-evaluate everything within [their selves], including the course of life and personal values’.69 (2009/3/20) and Chīda, Kono sakuhin wo yonde hon wo yomu you ni natta [I began to read books after reading this work] (2004/9/28).] Not only do these responses reflect the nature of popular literature as a reflection of one’s ideals, they confirm Hijikata is popularly imagined and loved as a hero driven by self-determination.

Conclusion

The following findings could be drawn from identifying popularly imagined Hijikata Toshizō as an autonomous, strong-willed hero. Firstly, as taishū bungaku entertains its audience by appealing to their philosophy and sentiments, readers’ attraction to Toshizō in Moeyo ken could be evidencing their sympathy for and synchronisation with the self- determining hero. The character’s appeal must be considered in light of the fact that he was formulated in tune with the zeitgeist of rapid economic development within Japan during the 1970s. Dreaming of self-actualisation amidst economic vivacity, the masses would have easily identified with Shiba’s pugnacious, peasant-born hero who actualised himself into the vice commander of Shinsengumi during the dynamic Bakumatsu period. However it should also be noted that individual drives and aspirations did not characterise Japanese society in those times as Japan astonished both domestic and international observers with her display of strong communitarianism.70 That is, the people needed to conform to social roles imposed by social and structural constraints embedded within their communities and organisations such as the workforce, school, neighbourhood and household. In this sense, individuals’ desire for self-determination could have been frustrated by constraints in their social realities. It is also likely that this frustration was also aggravated by the strike of consumerism and materialism, which further befuddled individual searches for personal philosophies about life. With the demand for conformism on their shoulders and lost in the quest for self identity, the masses would have found Toshizō’s strong sense of self identity and his strength to defy the conventions to actualise himself tremendously attractive.

Secondly, the depiction of Tōshirō, the contemporary version of Hijikata Toshizō, as a self-determining hero in Gintama indicates that the masses’ empathy and yearning for an autonomous hero has not diminished in modern-day Japan. Indeed, present romanticisation of Hijikata in this manner is most likely attributable to the enduring popularity and influence of Shiba’s characterisation of the hero. Yet a close examination of Tōshirō’s socio-historical context suggests that the nature of current demand for a self-determining hero is not identical to the masses’ attraction to Toshizō in earlier times. No doubt contemporary idolisation of Hijikata as an autonomous hero is also a likely result of the public’s frustration with finding and pursuing their individual goals. But they are frustrated for different reasons because it has become apparent that Japanese society has also lost a sense of direction. That is, not only are people’s efforts to find their individuality being hindered by social and cultural constraints, the society is also incapable of providing the masses with a sense of direction as it is besieged by various problems such as a fading economy, increased demand for families and individuals to undertake jiko sekinin (self- responsibility), threats to national security and the draining pension fund, to note a few.71 As a product of the 2000s, Tōshirō’s display of self-determination should be appreciated as a response to these problems. The masses of this age have witnessed the dangers associated with conforming to social demands as the society cannot assure the people of their future course. Consequently, they face greater uncertainty and apprehension, and have little hope for the future’.72 In this context, it is not surprising that Tōshirō is idolised as a modern-day hero since he is aware of the kind of life he wishes to lead, and is able to put it into practice.

This difference in Tōshirō’s textual context also relates to the final finding to be discussed in this article. It has been noted that the dynamics between the vice commander and Shinsengumi in Moeyo ken and Gintama are different as Toshizō seeks death as a Shinsengumi fighter and Tōshirō risks death to protect other Shinsengumi members. This signifies a notable shift in the masses’ yearnings as their contemporary hero is not only autonomous, but also shares a filial kinship with people in his surroundings. As contemporary Japanese society has become stripped of the myth of homogeneity and tainted with concerns for increasing disparity and isolation, her people have come to crave a sense of community. In this climate, reincarnating Hijikata into a lone wolf would have been insufficient to create a popular hero. Tōshirō could become popular in the twenty-first century because his strong bond with Shinsengumi members constitutes the backbone of his personality in addition to his drive for self- determination. With their backdrop clouded by frequent media reports about problems of hikikomori, family breakdowns and neighbours turning into strangers, the public could only admire Tōshirō, who chooses to protect Shinsengumi, his community.

Readers are kindly reminded that popular understanding of Shinsengumi’s spirit could be located in its vice commander, Hijikata Toshizō, because his dedication to the organisation and his death as the end of Shinsengumi are indispensable to the myth of Shinsengumi. In this respect, reproductions of Hijikata in Moeyo ken and Gintama could be appreciated as reflecting popular imaginations of Shinsengumi as autonomous heroes. Equating such a perception of Shinsengumi to the Japanese public’s imagination requires further research involving a wider number of samples across different time periods, and a more systematic methodology. But this study nonetheless provides a foundation to understanding a social phenomenon never scrutinised previously; future studies about the relationship between popular heroes and public consciousness in contemporary Japan could begin by theorising the romanticisation of Shinsengumi as evidence of the public’s desire for self-determination and a sense of belonging.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- All translations from Japanese to English including any associated errors and omissions in this article are my own unless otherwise stated. ↩

- Heibonsha, Nihonshi daijiten, 1445. For Shinsengumi’s history, see: in English, Turnbull, The Samurai Swordsman, pp. 180-192, and Hillsborough, Shinsengumi; and in Japanese, Matsuura, Shinsengumi. ↩

- Search result is correct as of 24 June This may include multiple entries of a work because some popular works are re-printed in different formats, different editions and such. But this does not void that there is a large number of products related to Shinsengumi. ↩

- An example of this is Shimozawa Kan’s historical fiction, Shinsengumi shimatsuki, first published in 1928. ↩

- Ozaki, Taishū bungaku ron, p. 430. ↩

- Saaler, Politics, Memory and Public Opinion, p. 152. ↩

- The novel was serialised from November 1962 to Mach 1964 in a magazine, Shūkan bunshun (Weekly Bunshun), and later published in hardcover and pocket sized editions. In this article, I use the latter, Shiba, Moeyo ken jō and Moeyo ken ge. ↩

- Taishū bungaku literally translates into mass, popular literature, fiction. Here, the term popular literature is mainly used but both mass and popular will be used to refer to taishū as explained in the body text. ↩

- In Japanese, Sorachi, Gintama; and in English, Gin Tama. Serialised in Japan since 2003, and since 2006 in the United States, the series is still under progress. I refer to the English edition, Gin Tama, on some occasions because I could not access the Japanese version. ↩

- Moeyo ken was voted as the best fictionalisation (novel or manga) of Shinsengumi in a survey published in the November 2003 edition of Da Vinci, a monthly literature This information is sourced from the cover page of Moeyo ken. Despite my efforts, I could not obtain a copy of the magazine to verify the publisher’s claim. Shiba, Moeyo ken jō, title cover. ↩

- An example of this is Sorachi’s characterisation of Shinsengumi in Gintama. This will be elaborated later in the article. ↩

- Saaler, op. cit., p. 152. ↩

- Saaler, op. cit., p. 152. ↩

- Matsuura, op. cit., pp. ii-iii. ↩

- Shaw, Contemporary Japanese Literature’, p. 292. See also, Ozaki, Taishū bungaku, p. 33. ↩

- Shiraishi Kyōji is a proponent of such an argument, see Suzuki, Nihon no bungaku wo kangaeru, pp. 151-78. ↩

- See Stretcher, Purely Mass or Massively Pure?’, and Kato et , Handbook of Japanese Popular Culture, p. xvii. ↩

- Mack, Accounting for Taste’, pp. 307-8. 19 Ibid., p. 301. ↩

- Ibid., p. 301. ↩

- Nakamura, Contemporary Japanese Fiction, pp. 138-143; Stretcher, Beyond ”Pure” Literature’, pp. 370-4. ↩

- Seidensticker, The ”Pure” and the ”in-Between”’, p. 181. ↩

- Kato, A History of Japanese Literature, p. 288. ↩

- Ozaki, Taishū bungaku ron, p. 22. ↩

- It should be noted that despite their buying power, consumers, particularly fans (poachers’) of popular cultural products, are also subject to power differential against the producers (the landowners’), see Jenkins, Textual Poachers, pp. 28-33. ↩

- Sakai, Japanese Popular Literature, p. 311. For a comprehensive overview of the development of Japanese popular literature, see Sakai, op. cit., and Suzuki, op. cit. ↩

- Gramsci’s argument is relevant to our inquiry as the Italian readership of popular literature referred to in his studies is reasonably varied like the taishū in this study; they include educated urban proletariat, petty bourgeoisie and illiterate or semi-literate listeners who heard spoken popular literature. Also, like the themes and styles of postwar Japanese popular literature, Gramsci claims that Italian popular literature is also diversified and sophisticated, encompassing remnants of earlier dominant literary forms (like romances of chivalry)’, scientific conceptions of the world’ as well as ”artistic” literature’. Gramsci et al., Selections from Cultural Writings, pp. 343-44. ↩

- Gramsci et al.,op. cit., p. 347. ↩

- Gramsci et al., op. cit., p. 348. ↩

- Sakai, op. cit., p. 190, and Ozaki, op. cit., pp. 444-445. ↩

- Sakai, op. cit., p. 294. ↩

- Katō, Nihon bungakushi josetsu vol. 5, pp. 573-4. ↩

- This is not a claim to present the readership of taishū bungaku as being representative of the Japanese. Popular consciousness derived from popular literature could only be attributed to a particular section of Japanese people, i.e. readership of the work under scrutiny. Attempts to associate values distilled in popular fiction with the Japanese public require an examination of the work’s readership to assert that the values correspond to the public’s sentiments. ↩

- Ozaki, op. cit., p. 179. ↩

- Gramsci et al., op. cit., p. 350. ↩

- Emphasis is my Sorachi, Gin Tama Vol. 6, p. 126. Burn My Sword’ is the English translation of Moeyo ken by the manga’s translator. ↩

- Nishimura, Saraba, waga seishun, pp. 31, 115, 165; Schilling, The Encyclopaedia of Japanese Pop Culture, pp. 228-29; and Kinsella, Adult Manga: Culture and Power, pp. 55, 166-9. ↩

- Sorachi, Gin Tama Vol. 6, p. 126. ↩

- For example, female readers polled by Oricon voted Gintama as the funniest manga in 2008. Oricon, Ichiban waratta manga’. Female readers, particularly fujoshi (literally rotten women, who are interested in original and parody works that depict romantic and often, erotic homosexual relationships), also constitute a notable proportion of Jump manga readership. Aoyama, Eureka Discovers Culture Girls, Fujoshi, and BL’. For fujoshi‘s interest in Jump manga, see Kinsella, Japanese Subculture in the 1990s’, p. 301. ↩

- Kinsella, Adult Manga: Culture and Power, p. 49. ↩

- Yoshikawa, Shinsengumi!! hijikata toshizō saigo no ichinichi and Yoshikawa, Shinsengumi!. NHK, or Nihon Hōsō Kyōkai, is a national broadcasting service in Japan akin to the United Kingdom’s BBC. ↩

- Author’s Lee, Taiga dorama janru’, p. 149. For a detailed account of the cultural ramifications of taiga dorama, see, pp. 161-164. ↩

- Shinsengumi! was written by Mitani Kōki, whose approach to Shinsengumi and Hijikata deviates from Not only did Mitani focus the drama on Kondō instead of Hijikata, he used hope as a key theme for both dramas. For these reasons and also, since his hero, Kondō, does not appear to have been a popular hero like Shiba’s Hijikata, Shinsengumi! was not selected for the comparative study. ↩

- NHK, Shinsengumi! Zokuhen’. ↩

- Most reviewers of Moeyo ken did not differentiate between the fictional and actual Hijikata in contrast to reviewers of Gintama, who made such distinctions. For this reason and for practicability, Gintama reviews have been omitted from analysis in this But where a reviewer made the differentiation, I noted the reviewer’s perception of the actual figure as his or her view of Hijikata Toshizō. ↩

- Steiner, Private Criticism in the Public Space’. ↩

- Matsumoto, Shiba ryōtarō – shiba bungaku, pp. 13, 47-8. ↩

- Ibid., p. 468. ↩

- See Morris, The Nobility of Failure, for the well-known account of Japanese tragic A close examination of the conditions’ of tragic heroes suggests Hijikata is not one of them because he successfully pursues his cause (to accomplish himself as a fighter) unlike the tragic heroes who fail to achieve their causes. In this respect, Hijikata and thereby Shinsengumi are more aligned with the retainers in Chūshingura who successfully avenged their lord’s death. See Morris, op. cit., pp. xxi-xxii and Smith, The Case of the Akō Gishi, pp. 90-91. ↩

- For a discussion of Shiba’s position as a national writer’ of Japan, and the nexus between his works and Japanese nationalism, see Keene, Five Modern Japanese Novelists, pp. 85-100, and Nakao, The Legacy of Shiba Ryotaro’. ↩

- Jenkins, op. cit, p. 23. ↩

- Owee is a parody of Wii, a game console produced by Nintendo Electronics. ↩

- Readers familiar with Japanese history may find these names humorous for they are identical except for one kanji character to the names of historical figures Saigō Takamori and Tokugawa Iemochi, the 14th and second last Bakufu shogun. ↩

- Sorachi, Gintama 2, p. 59. ↩

- Sorachi, Gin Tama Vol. 3, p. 39. ↩

- Shiba, Moeyo ken jō, p. 401. ↩

- This arc spans from episode 158 to 168 in Sorachi, Gintama pp. 19-20. ↩

- Hikikomori refers to a reclusive youth, who withdraws from society and refuses to interact with people other than their family for more than six months for reasons other than mental illness: Andy Furlong, The Japanese Hikikomori Phenomenon’, p. 309. ↩

- Sorachi, Gintama 19, p. 70. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 121-122. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 127-128. ↩

- Sorachi, Gin Tama Vol. 6, p. 121. ↩

- Sorachi, Gintama Vol. 20, p. 9. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 13-14. ↩

- Ibid., p. 14. ↩

- Deci and Ryan, Handbook of Self-Determination Research, 5, p. 27. ↩

- Ryan, The Nature of the Self ‘, p. 209. ↩

- VanderStoep and Johnston, Research Methods for Everyday Life, p. 183. ↩

- Sūjī (2006/07/25). ↩

- Maruchi, Shinsengumi ni kyōmi no nai kata ni mo osusume desu [I recommend this book also to those who are not interested in Shinsengumi ↩

- Vogel, Japan as Number One and Murakami et al., Bunmei to shite no ie shakai. ↩

- For an analysis of the various risks present in contemporary Japan, see Kingston, Contemporary Japan. ↩

- Ibid, p. 20. ↩