Girls Just Want To Have Fun: The Portrayal of Girls’ Rebellion in Mobile Phone Novels

Published June 29, 2017

Pages 28-47

https://doi.org/10.21159/nvjs.09.02

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney and Marie Kim, 2017

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

New Voices

in Japanese Studies

Volume 9

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2017

Abstract

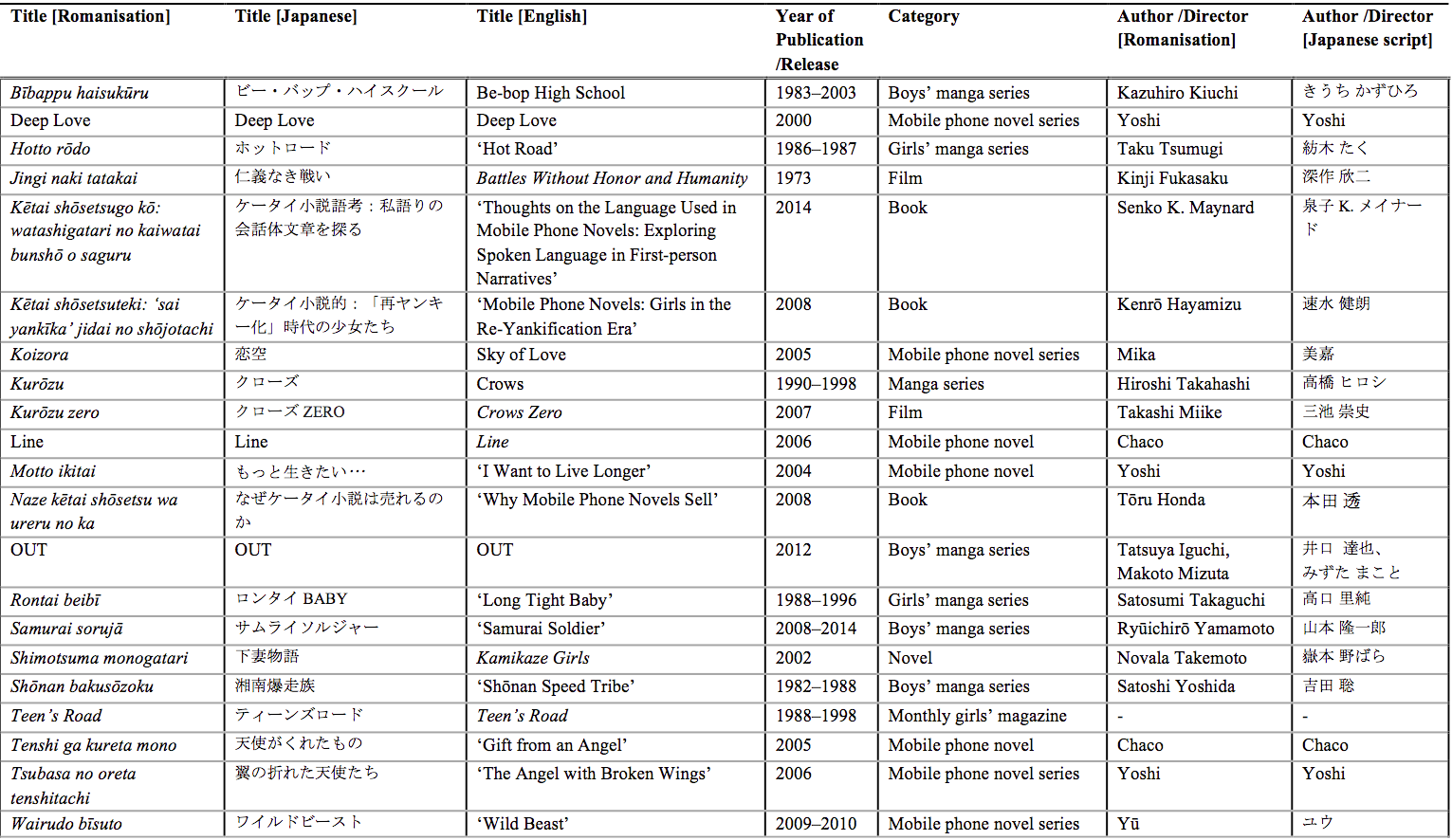

The rise of kētai shōsetsu—digital novels written and shared on mobile phones, predominantly by girls—in the late 2000s caught the attention of Japanese critics and journalists, as a new literary phenomenon that was taking the world of Japanese girls’ literature by storm. In 2008, journalist Kenrō Hayamizu published a book titled Kētai shōsetsuteki: sai yankīka’ jidai no shōjotachi [Mobile Phone Novels: Girls in the Re-Yankification Era’], in which he draws a parallel between mobile phone novels and the yankī culture that has its roots in 1980s youth culture. In this pioneering work, Hayamizu interpreted the emergence of the mobile phone novel as a sign of a yankī cultural revival. Although there is undoubtedly a strong parallel between mobile phone novels and yankī culture, the argument that this is simply a revival’ of the 1980s rebellious youth culture significantly undermines the role that girls play in the cultural production of such novels. Using the Wild Beast series [2009—2010] by Yū as a case study, this paper argues that the girls writing and reading mobile phone novels are reimagining yankī culture as their own.

INTRODUCTION

In 2008, journalist Kenrō Hayamizu published a book titled Kētai shōsetsuteki: sai yankīka’ jidai no shōjotachi [Mobile Phone Novels: Girls in the Re-Yankification Era’], a pioneering work on kētai shōsetsu (ケータイ小説; mobile phone novels) that explores the trend among Japanese girls1 of writing, publishing, and reading novels’ online via their mobile phones. Hayamizu traces the origins of this literary genre to the 1980s by drawing a parallel between the themes of mobile phone novels and yankī (ヤンキー; delinquent) culture—a distinct type of Japanese rebellious youth culture that emerged in the 1980s. Hayamizu goes as far as to claim that the rise of mobile phone novels signals a revival of yankī culture. Although there is a strong parallel between the two, I disagree with the way he considers the use of yankī elements in mobile phone novels simply as a sign of re-Yankification’ in contemporary Japanese girls’ culture. Focusing on the portrayal of girls’ rebellion in the Wairudo bīsuto [Wild Beast’; 2009—2010] (hereafter, Wild Beast’) series2 by the author known simply as Yū [b. unknown], I examine the way yankī culture is used in the text, arguing that mobile phone novels represent a strategic reimagining of yankī culture by the girls who are writing and reading the genre.

Mobile phone novels first attracted the attention of journalists in the late 2000s, when numerous mobile phone novels that had been republished in print form began to appear in Japan’s bestseller lists (Mizukawa 2016, 61).3 Hayamizu’s book, and another by Tōru Honda titled Naze kētai shōsetsu wa ureru no ka [Why Mobile Phone Novels Sell’; 2008], were published in the same year, and these ground-breaking works were soon followed by commentary from academics such as Larissa Hjorth, who had already been observing mobile phone usage among Japanese adolescent girls (Hjorth 2003). More recent scholarly publications, such as Senko K. Maynard’s (2014) book Kētai shōsetsugo kō: watashigatari no kaiwatai bunshō o saguru [Thoughts on the Language Used in Mobile Phone Novels: Exploring Spoken Language in First-person Narratives’] and Jun Mizukawa’s (2016) article ”Reading On the Go’: An Inquiry into the Tempos and Temporalities of the Cellphone Novel”, indicate that scholarship on the mobile phone novel is slowly but steadily growing, attracting scholars from various fields, ranging from linguistics to cultural studies. However, most research has been from the perspectives of sociology or cultural studies rather than literature, as many literature scholars still seem reluctant to recognise these novels as bona fide literature (Hayamizu 2008, 3; Honda 2008, 3). Mizukawa also notes that the existing discourse of mobile phone novels in literary studies focuses predominantly on the discussion of ”literary merit”, with many scholars continuing to dwell on such novels’ apparent lack of literary sophistication (Mizukawa 2016, 61—62). This reluctance to accept mobile phone novels notably seems to stem more from the fact that they are written by adolescent girls, who ”know nothing” about literature (Hayamizu 2008, 3), rather than the fact that a mobile phone is used to create them.

The term shōjo (少女), meaning young girl’, can be traced back to the eighteenth century, but it first emerged as a ”social entity” at the end of the nineteenth century (Aoyama and Hartley 2010, 2). In their studies of shōjo literature, scholars Tomoko Aoyama and Barbara Hartley (2010) argue that Japanese female writers and their cultural productions have for generations been discredited as ”lightweight, narcissistic, consumer-oriented and lacking in substance” (2). Countering such dismissive appraisal by men in the publishing industry, as well as literary critics, Japanese girls began to create a ”parallel imagined fantasy world”, in which their aspirations are acknowledged and desires fulfilled through various kinds of cultural production (Aoyama and Hartley 2010, 2). Although Aoyama and Hartley’s study focuses on shÅjo novels, it also includes manga, as well as dōjinshi (同人誌; amateur publications or fan fiction), as examples of girls taking an active role in cultural production (Aoyama and Hartley 2010, 3).4 The mobile phone novel is the most recent development in this evolution of shōjo literature, as the writers incorporate a new platform for sharing stories, made available by the development of the internet and access to mobile phone technology.

In the late 2000s, amid a sudden burst of academic interest in yankī culture, scholars like Tarō Igarashi and Kōji Nanba published research on this type of rebellious youth culture. Since then, however, despite the prevalence of yankī culture in Japanese popular media, academic research into the subject has somewhat declined. More importantly, previous studies, including those by Igarashi and Nanba, have been male-oriented, focusing on rebellious boys. This paper therefore attempts to extend yankī discourse to include girls, through a mobile phone novel case study. The paper firstly explores the origins of the mobile phone novel and its links to the rebellious youth culture of the 1980s, particularly the motorcycle gangs. It then examines the fictional representation of rebellious girls in the Wild Beast series and the way this borrows from earlier male-oriented yankī culture to create a shared parallel imagined fantasy world’ of shōjo literature within the sphere of mobile phone novels.5

BACKGROUND

The Origins of the Mobile Phone Novel

Technically, the term kētai shōsetsu’ can refer to any digital fiction written and shared on a mobile phone. Yet, scholars and critics in this area have tended to focus on works produced and read by adolescent girls. Jane Sullivan (2008), for example, describes mobile phone novels as ”pulp fiction” written and read by teenage girls and women in their twenties (28). One of the reasons for defining mobile phone novels as part of girls’ culture is that they are said to have originated from a User Created Content (UCC) website called Magic i-land (魔法のiらんど), which was first launched in 1999. This website specifically catered to adolescent girls, providing them with a platform where they could upload and share diary entries, images, poetry and stories (Hjorth 2009, 26; Hayamizu 2008, 7—8; Honda 2008, 20—21). The first mobile phone novels were actually written by professional writers experimenting with a new writing platform, but they only became a literary phenomenon when ordinary’ girls began to write and share their own stories online via mobile phone (Hjorth 2009, 26).

The mobile phone novel market continues to thrive: Magic i-land claims to have 1.5 billion views per month (Kadokawa Corporation 2017), while its rival site Wild Strawberry (野イチゴ), established in 2007, claimed 600 million per month in 2015 (Starts Publishing Corporation 2016). Even so, girls remain the primary target audience and there is little genre diversification. At a glance, Magic i-land and Wild Strawberry seem to offer a wide range of stories, including horror, mystery, verse novels, and even what they claim to be junbungaku (純文学; lit., pure literature’ or high literature). Despite this seemingly wide range of genres, however, the majority of texts are in fact teen romances (or love poems) that have incorporated elements of other genres, such as horror or mystery, making them subcategories of teen romance rather than separate genres. The dominance of teen romance is best illustrated by the reception of works by the popular mobile phone novel writer Yoshi.6 His teen romance series Deep Love [2000] became a bestseller, selling more than 25 million copies when published in paperback form. However, his second novel, Motto ikitai [I Want to Live Longer’; 2004], which included horror and science fiction elements, was considered a failure as disappointed publishers were left with 200,000 copies of dead stock due to poor sales (Hayamizu 2008, 83). This illustrates how romance had already become the conventional formula for mobile phone novels. In other words, romance is what readers had already come to expect when reading a mobile phone novel.

The mobile phone novel has rapidly developed its own set of conventions, mostly by borrowing from existing genre conventions in popular media, such as manga and film, and adjusting them to satisfy readers (especially in terms of romance). One of the recurrent narratives is the girl-meets-rebel type of teen romance, which combines elements of romance with tales of teenage rebellion—a genre I refer to as ochikobore seishun shōsetsu (おちこぼれ青春小説; juvenile delinquent novels).7 Elements of yankī culture, such as bōsōzoku (暴走族; teenage motorcycle gangs; also used to refer to gang members) and sōchō (総長; gang leaders), which were instrumental in the emergence of ochikobore seishun’ narratives in Japanese adolescent literature, are used abundantly in mobile phone novels. Although a female heroine falling in love with a rebel or an outsider can be considered a universal plot in popular media, and especially in girls’ literature, the girl-meets-rebel narrative in mobile phone novels specifically references yankī culture rather than more contemporary forms of teenage rebellion in Japan. Both Magic i-land and Wild Strawberry have special pages recommending novels that include yankī elements. Furthermore, terms like bōsōzoku’ and sōchō’, as well as furyō (不良; delinquent),8 have become keywords for searching and categorising girl-meets-rebel romances on these mobile sites.

Yankī: The Rebellious Youth Culture of the 1980s

The origin of the term yankī’ is debated to this day. The most prominent theory is that the English derogatory term Yankee’ was used by Japanese adults to refer to delinquent youth in postwar Japan because they were copying the fashion and hairstyles of Americans living in Japan (Nagae 2009, 34).9 From the late 1970s, as the Japanese economy began to recover from the devastation of war, Japanese youth developed their own distinct fashions, language and subcultures with their newly acquired disposable income.10 At the time, there was also a revival of 1950s American youth culture on a global scale, with films like The Wild One [1953] and Rebel Without a Cause [1955] being redistributed as nostalgic commodities, specifically targeting those who had been teenagers in the 1950s (Ōyama 2007, 216). When these films were redistributed in Japan, they attracted a new generation of teenagers who quickly adopted elements of 1950s American youth culture to create their own rebellious teen identity (Narumi 2009, 80—81). For these Japanese teens of the 1980s, the characters of Johnny Strabler (The Wild One) and Jim Stark (Rebel Without a Cause) became icons of teenage rebellion. Fast cars, motorcycle gangs, black leather jackets, blue jeans, pompadour hairstyles and rock n’ roll music became tools for performing a teenage rebel identity. Additionally, tsuppari (ツッパリ; delinquent youth)11 culture, which derives from the 1970s anti-school rebellious youth culture, continued to thrive in Japan into the 1980s and gradually merged with these American elements to form yankī identity. Thus, yankī culture is an amalgam of various elements that the general public considered menacing. For example, although Japanese motorcycle gangs initially mimicked 1950s American style, they gradually added symbols of Japan’s right-wing nationalist past, such as the imperial era flag and kamikaze fighter uniforms (Narumi 2009, 80—81).

In the early 1980s, these rebellious teens, especially those involved in motorcycle gangs, were initially feared by peers and considered problem youth by society. While news media frequently reported yankī-related riots and violent antics during the 1980s, popular media such as films and shōnen manga (少年漫画; boys’ comic books or graphic novels) began to counter such negative portrayals by depicting yankī as charismatic rebel heroes. Kazuhiro Kiuchi’s Bībappu haisukūru [Be-Bop High School; 1983—2003] and Satoshi Yoshida’s Shōnan bakusōzoku [Shōnan Speed Tribe’; 1982—1988] are considered quintessential yankī narratives. The plots of these manga revolve around a group of delinquent students who spend their high school years rebelling against school and society. Contrary to the way the yankī were being portrayed in news media at the time, these yankī protagonists were depicted as mischievous and rebellious but charismatic, honourable and ultimately moral; they often engaged in delinquent behaviour and disobeyed school rules, but they never committed serious crimes.12 The success of these manga led to a plethora of similar narratives that glamourised teenage rebellion, such that the depiction of the yankī protagonist as an honourable hero or a good bad boy’13 became stereotypical in post-1980s Japanese popular media.

Although the term yankī’ can refer to both delinquent boys and girls, there are gender-specific labels such as sukeban (スケ番) for female delinquents, and redīsu (レディース) for female members of girls-only motorcycle gangs and the girlfriends of bōsōzoku. In the 1980s, elements of yankī culture were also evident in shōjo manga (少女漫画; girls’ comic books or graphic novels). For example, works like Hotto rōdo [Hot Road’; 1986—1987]—a pioneering girl-meets-rebel tale by Taku Tsumugi—incorporate the good bad boy characterisation of bōsōzoku into teen romance, while Satosumi Takaguchi’s Rontai beibī [Long Tight Baby’; 1988—1996] depicts the rebellion of two sukeban.14 Although Hotto rōdo focuses on the heroine’s romance with a good bad boy, and Rontai beibī focuses on the friendship between two sukeban heroines, both works glorify the rebellious girls of yankī culture. Takaguchi’s work in particular has been described as a female version of Bībappu haisukūru (Kobayashi 2014, 55).

Despite the presence of girls within yankī culture, research into the culture has focused predominantly on boys. Ramona Caponegro (2009) has noted how rebellious girls in 1950s America have similarly failed to attract critical attention (312—13), suggesting this underlying discursive bias or sexism in the discourse of teenage rebellion is not unique to Japan. Scholars such as Ikuya Satō, as well as Tarō Igarashi and Kōji Nanba mentioned previously, have conducted extensive analyses of male yankī culture, but little effort has been made to study girls, who are only mentioned as a supplementary detail in such analyses of boys’ rebellion. Furthermore, while the portrayal of male yankī continued to thrive in popular media throughout the 1990s and 2000s,15 representations of female versions of yankī, such as sukeban and redīsu, have sharply declined since the 1980s. Works such as the commercially successful Shimotsuma monogatari [Kamikaze Girls; 2002] by Novala Takemoto [b. 1968] that tells the tale of an unlikely friendship between two girls—one a yankī (or redīsu to be more specific) and the other a rorīta (ロリータ; Lolita)16—are rare.

Sharing Stories

When exploring the link between mobile phone novels and yankī culture, Hayamizu focuses on the process of sharing stories, rather than exploring the actual use of yankī-related terms like bōsōzoku in the novels themselves. He argues that mobile phone novels originate in teenage girls sharing their own stories, especially their miseries, through readers’ pages in teen magazines such as Teen‘s Road [1988—1998] (Hayamizu 2008, 86—89). Teen‘s Road specifically targeted redīsu and its pages were filled with images of girls wearing tokkōfuku (特攻服; bōsōzoku uniforms’ inspired by kamikaze fighter pilot apparel), with bleached hair and thick makeup, looking rebellious. Yet, he points out that the content was largely similar to that of any other teen magazine, with articles discussing a range of adolescent issues like bullying, friendship and boys, rather than the issues such rebellious girls were known for and one might expect in a magazine catering to them: namely, gang wars and brawling (Hayamizu 2008, 87). Similarities in content between Teen‘s Road and other mainstream girls’ magazines suggest that although the girls in yankī culture performed their rebellion through distinct fashion and style, they also shared common concerns with mainstream girls in terms of everyday adolescent issues, such as boys and peer pressure.

That being said, it is the darker, more serious issues such as teenage pregnancy, abortion, violent boyfriends and death intermittently discussed in Teen‘s Road that Hayamizu refers to in order to draw a parallel between the girls contributing their stories to Teen‘s Road in the 1980s and girls depicted in mobile phone novels. He uses the following reader’s contribution from the March 1995 issue of Teen‘s Road to illustrate this point:

I am a 13-year-old yankī. One night in the spring, I lost my boyfriend to one of my friends. I was so sad, I walked through the bar district crying. I heard someone honking their car horn and I turned around. The driver looked about 20 years old. He got out of the car and asked whether I was okay. His kindness just made me cry harder. His name was Tetsuya; he was 18. […] ”Why were you crying?” he asked. So I told him everything. My eyes overflowed with tears. He held me tightly. […] One day, he said, ”Go steady with me.” I was so unbearably happy. From then on I lived with him, and before I knew it, five months had flown by. […] On 30 July, I was waiting at home for Tetsuya to finish work when the phone rang. It was one of the old boys from the gang. He said, ”Tetsuya was involved in a motorbike accident. He might not make it. Come to XX Hospital.” […] ”Rie, I’m so glad I met you. I’m sorry I couldn’t make you happy.” And with that, he quietly passed away while holding my hand. I will never forget that night. Tetsuya, I’m so glad I met you too.[17「13才のヤンキーな女です。春のある夜、つき合っていた彼氏を友達に取られて哀しくて泣きながらスナック街を歩いていました。すると後ろからクルマのクラクションが聞こえ、振り向くと20才くらいの男の人が一人、乗っていました。その人はクルマから降りて、『大丈夫?』と聞いてくれて、その優しい言葉にまた涙がこぼれました。その人の名は『てつや』18才でした。……『なんで泣いてたんだい?』と聞かれたので、私は今までのことを全部話しました。涙がこぼれ落ちました。てつやは私を強く抱きしめてくれました。…… ある日、彼が『お前俺と付き合え』と言ってくれて、私は嬉しくてたまりませんでした。そして、てつやの家に一緒に住むことになり、あっという間に5か月ぐらいたちました。…… 7月30日、私は徹夜の家で、彼のバイトが終わるのを待っていました。TELが鳴って、『徹夜が単車で事故った、危ないかもしれない。早く○○病院にこい』と族のOBの人から。…… 『リエ、お前に会えて良かった。幸せにしてやれなくて、ごめんな…』そしててつやは私の手を握ったまま、静かに息を引き取りました。私は、あの7月30日の夜を忘れません…。てつや、あなたと出会えて本当に良かった。」]

(Hayamizu 2008, 89—91)

Hayamizu points out that such reader confessions read like a plot summary for a typical mobile phone novel (Hayamizu 2008, 91). These so-called confessions are so overly dramatic that it is almost as though the contributors are playing the part of a heroine from a tragic teen romance. Stories like Rie’s are so common in Teen‘s Road that Hayamizu describes them as symptomatic of the ”inflation of misery and misfortune” (不幸のインフレ) among teenage girls sharing such stories (Hayamizu 2008, 94). Tōru Honda, another scholar to focus on the sharing of misery in mobile phone novels, has proposed a list of seven recurrent tropes, including prostitution, rape, teenage pregnancy, substance abuse, terminal illness, suicide and true love (Honda 2008, 12—18). Both Honda and Hayamizu argue that personal tragedies, or ”sins” according to Honda, have become a crucial part of mobile phone novels (Hayamizu 2008, 92—94; Honda 2008, 12—18).

Looking more broadly at girls’ culture in the 1980s and 1990s (prior to the internet) indicates that sharing personal stories in the form of letters, kōkan nikki (交換日記; exchange diaries) and reader contribution pages in magazines like Teen‘s Road were especially popular modes of communication among teenage girls at the time (Katsuno and Yano 2002, 222). The exchange of personal stories between girls in print can be traced back to the late nineteenth century, when magazines specifically catering to young girls were first published. Aoyama and Hartley (2010) note that until very recently, the publishing sphere was dominated by men, and even girls’ magazines were edited by male editors who attempted to control the material girls were reading; thus, girls began to resist male control by contributing their own stories in the form of essays and letters to these magazines (3). When this historical context of girls exchanging stories is taken into account, the sharing of stories including mobile phone novels can be seen as an act of rebellion whereby girls attempt to take control of the production of the culture they live and consume.

PORTRAYAL OF GIRLS’ REBELLION IN THE WILD BEAST SERIES

The Bad Girl and the Tomboy

Leerom Medovoi (2005), who has examined 1950s American teenage rebellion and its portrayal in popular media, categorises the portrayal of rebellious girls at the time into two types: ”bad girls” who date rebels (often in order to substitute for incompetent or absent fathers), and ”tomboys” who perform rebellion by assuming a masculine identity (267). He argues that a heroine’s romantic relationship with a rebel is also a form of rebellion, as she is refusing to be a good girl (i.e., by dating a good boy) (266). Although Medovoi’s theorisation of fictional rebellious girls derives from American popular culture, similar observations can be made of the way rebellious girls are portrayed in yankī narratives, especially in girls’ manga. For example, the protagonist of Hotto rōdo falls into the category of the bad girl, while the two protagonists of Rontai beibī are tomboys. These two stereotypical portrayals of rebellious girls are also evident in mobile phone novels, including Yū’s Wild Beast series.

Ayaka: Rebellion through Dating a Rebel

Often in tales of teenage rebellion, the female character’s primary role is to be the damsel-in-distress to emphasise the positive traits of the rebellious delinquent hero, so that he is read as a good bad boy. In the Wild Beast series, Ayaka faithfully plays this role in depicting her boyfriend, Ryūki, and his gang—called Yajū (野獣; lit., wild beast’)—as good bad boys. Their wayward behaviour, such as smoking and drinking, is downplayed, while their positive traits, including loyalty, chivalry and a strong sense of moral right and wrong, are highlighted because they are the ones who repeatedly rescue or protect the heroine from danger.

Also, in a typical girl-meets-rebel narrative, the protagonist is observing her romantic partner’s rebellion rather than actively engaging in teenage rebellion herself. For example, when Ayaka begins a relationship with Ryūki, she becomes part of the gang by association. Throughout the series, she spends time with Ryūki and his gang members at their headquarters, and even joins them when they ride out. As the girlfriend of the leader, Ayaka is allowed to sit next to him in the back seat of his black Mercedes Benz, and is driven around by one of the members while the rest of the gang follow on their motorcycles. Her passive participation (i.e., riding alongside her boyfriend) indicates that she is accepted by the gang as their leader’s girlfriend, but not as a fellow member. Her position (or lack thereof) is emphasised throughout the series as Ryūki repeatedly orders Ayaka not to interfere in gang matters, reminding her that she is his girlfriend and not an official gang member (Yū 2009b, 238—44). The fact that Ayaka is an observer and not an active participant in bōsōzoku activities underscores her position as a damsel-in-distress, whose primary function is to be rescued and protected by the rebel hero so that he may be portrayed as a good bad boy, under the existing genre-defining conventions of yankī narratives.

The narrator-protagonist’s position as a damsel-in-distress is established from the very beginning, as the two main characters meet when Ayaka jumps in front of an oncoming car in a suicide attempt, only to be rescued by Ryūki and his friend Mikage. This opening also draws attention to the heroine’s misery rather than her rebellion, as illustrated by the following monologue in the first chapter:

It’s good that I’m stupid. Because, you know, I don’t want to think too much at times like this. I used to hate being stupid, but right now, I’m glad that I am. I mean, I’ve been able to sleep at times like this because I’m an idiot. I may be an idiot, but I’m an idiot who is trying hard… I don’t think it’s good to try too hard. I hate thinking and I’ve been thinking hard ever since I got here…and I’m drained.[18「あたし、バカでよかった。こういう時、色々考えちゃうのは嫌だから。自分がバカなところ嫌いだったけど、今はすごくよかったって思ってる。でもまぁ、バカだからこのタイミングで眠っちゃおうって思ったんだろうけど、バカはバカなりに頑張ってて…頑張りすぎるってあんまよくない。あんまモノ考えんの好きじゃないのに、ここ最近ず~っと頭使ってたから…疲れたんだ、あたし。」]

(Yū 2009a, 7)

The narrator-protagonist’s desire to end her life seems sudden and without pretext, but it is gradually revealed that her reasons for attempting suicide stem from multiple miseries: guilt towards her hard-working mother; anger towards a father who has abandoned her; and frustration and fear due to peer pressure. At the same time, these miseries are what make the heroine a damsel-in-distress and the rebellious hero a good bad boy, because he eventually rescues her.

While Ayaka’s relationship with her mother (who is working hard to provide for her daughter after divorcing Ayaka’s father) is not antagonistic, Ayaka is convinced that she is a burden to her mother and is overcome by guilt at the thought of spending hard-earned money on things such as makeup and fashion merely to keep up with her school friends (Yū 2009a, 106). In addition, Ayaka blatantly blames her father for leaving them. The failure of her parents’ marriage has made her so pessimistic about love that she wonders if there is such thing as true love (Yū 2009a, 190). But through her experience with Ryūki, Ayaka changes her mind and the series ends with a statement of love from Ryūki, and the heroine revelling in happiness at the prospect of a future with him (Yū 2010, 258). By the end of the series, Ayaka is able to reconnect with her parents, but it is Ryūki and his marriage proposal that saves her from the miseries of a broken home: he has found full-time employment after graduating from high school and this means that Ayaka will be able to start a family of her own with him (Yū 2010, 258).

Another misery from which the rebellious hero saves the heroine is peer pressure and bullying from so-called school friends. Throughout the series, Ayaka expresses frustration at having to follow other girls, as shown in the following passage:

Every morning, I repeat the tedious task; styling my hair and carefully putting on makeup. I’m only in high school, yet I look like an office lady. I really hate looking like this—thick makeup, curly waves in my hair. But I have to because everyone else is wearing their hair in curls. Get ready and put some makeup on. I can’t be bothered with it all, but I have to, because it’s today, again.[19「毎朝毎朝めんどーな事の繰り返し。髪のセットと念入りな化粧。まだ高校生なのに、OL並みの身だしなみ 。あたしはあんまりこういうの好きじゃないのに。濃い化粧とか、クルクル巻き髪とか。でもしなきゃなんない。みんなしてる、クルクル巻き髪。身なり整えて、化粧して。めんどーでも、したくなくても、今日って日が来ちゃったからしなきゃなんない。」]

(Yū 2009a, 60)

Ayaka is weary of conformity but she is unable to stand up to the girls on her own. She is fearful of retribution to such an extent that she sees ending her life as the only solution. Ayaka’s initial effort to fit in with and be accepted by the girls at school is something to which many teenage readers can relate. The protagonist’s struggles with her school friends in the Wild Beast series shows how hairstyle, makeup and fashion are not just part of performing a group identity to differentiate members from non-members, but are also part of enforcing conformity and reinforcing commitment within the peer group. Refusal to conform results in punishment, and Ayaka is subjected to bullying after her eventual refusal to follow the group. For example, when Ayaka changes her mind about sleeping with an unknown man in a hotel room, an act of enjo kōsai (援助交際; lit., compensated dating’) arranged by her classmates, not only do they bully her, they attempt to have her raped by members of a rival gang to Ryūki’s (Yū 2009a, 195). This, however, is unsuccessful because Ayaka is rescued by Ryūki and his gang, further cementing their respective roles as the damsel and rebel hero.

As Caponegro (2009) points out in the American context, the more deviant forms of female identity are often neglected by academics (312—13). Yet, when it comes to the sexual behaviour of adolescent girls, both society and academics show great concern. For example, in contrast to the lack of scholarship on aspects of rebellious girls’ culture, such as sukeban or redīsu, there are abundant studies on enjo kōsai. In the late 1990s, the issue of enjo kōsai triggered mainstream moral panic when it was reported that girls as young as those in junior high school were participating in prostitution. Indeed, promiscuousness among girls continues to be seen as a sign of delinquency and enjo kōsai remains one of Japanese society’s major concerns (Ueno 2003, 320). As this concern increased during the 1990s, when media frequently reported girls engaging in enjo kōsai, scholars began to argue that enjo kōsai is one of the ways in which a girl might rebel against her parents, since a girl’s body is allegedly the property of her father (Ueno 2003, 318—19). For example, psychologist Chikako Ogura (2001) defines female adolescence as a period when a girl realises that she is not the owner of her body, and moreover that it ”serves someone else’s desire” (3). Chizuko Ueno (2003) observes how some scholars have even argued that when a girl sells her body she is exercising her right of ownership and challenging her father, making it an act of rebellion (323).

But the argument that enjo kōsai is a form of empowerment disavows or condones the exploitation of adolescent girls by adult males, and ignores the way that hegemonic masculinity operates within society. While it is adult males who seek out these girls, society views enjo kōsai as a girl’s problem and blame is laid mostly on those girls who ”shamelessly” offer their bodies for cash, while the male desire for underage girls is ”naturalized” (Ueno 2003, 321). Furthermore, such a view suggests that the only way for a girl to take control of her own body is through prostitution. Female protagonists like Ayaka challenge such arguments by demonstrating that enjo kōsai is far from being an act of reclaiming the body, as Ayaka, for example, is never in control during the process. She is only able to take control of her body by refusing, rather than engaging in, prostitution. For some girls, enjo kōsai may indeed be a form of rebellion against their parents, a means to gain financial power and satisfy their hedonistic desire for consumption. However, characters like Ayaka show that refusing can also be a powerful act of rebellion against peer and social pressures. Ayaka is unable to rebel against her classmates and stand up to them on her own, but her reluctance and eventual refusal to blindly conform can be interpreted as a hint of rebelliousness that is amplified when she comes into contact with the good bad boy. Her choice to date the leader of a bÅsÅzoku, instead of other more socially acceptable’ boys from her school, can also be interpreted as an act of rebellion, but it is somewhat overshadowed by her role as a damsel-in-distress, given the romance with the rebel hero who rescues her is the central plot of the series.

Ryō: Rebellion of a Tomboy

The Wild Beast series portrays another form of adolescent female rebellion through its secondary character Ryō, who is a former onna sōchō (女総長; female motorcycle gang leader) of the Yajū gang. In contrast to the damsel-in-distress who needs to be rescued and protected, Ryō is a strong independent woman who actively and independently performs rebellion against society through her bōsōzoku identity. Unlike Ayaka, Ryō’s relationship with the boys is one between equals. Despite having retired from the position of gang leader, she continues to associate with the gang and even rides out with them. The boys comment in awe that Ryō is one of the best riders; she can even outrun the police (Yū 2009a, 204).

When gender positioning within the bōsōzoku culture of the 1980s is taken into account, it becomes clear that Ryō’s equal status in the gang—or even superior status, since she had been leader—is a product of fantasy. The bōsōzoku of the 1980s was a heavily gendered space in which only males were referred to as bōsōzoku (Nanba 2009, 156); a female leader of a male-only bōsōzoku gang would have been extremely unlikely. According to author Natsuki Endō, the gender hierarchy in bōsōzoku culture even meant female riders were required to ride behind male riders.17By contrast, in Wild Beast, Ryō takes the lead during one of the gang’s ride outs, indicating that, at least within the world of Wild Beast, a girl can be an equal, or even superior, as long as she shows the skills and character of a bōsōzoku.

The use of the terms bōsōzoku’ and onna sōchō’ for Ryō, instead of redīsu’, symbolises her superior status and influence within the gang, and challenges the gender hierarchy that Wild Beast readers would likely face on a daily basis. The phenomenon of female readers vicariously enjoying an escape from gender hierarchy through female characters is well documented by Janice Radway (1991), who argued that reading romance novels is a ”way of temporarily refusing the demands associated with [females’] social role as wives and mothers” (11). Mobile phone novels offer similar forms of escape and vicarious pleasure. In Wild Beast, these are offered through both Ryō and Ayaka: Ryō as one of the boys (or even better, as their leader); and Ayaka, through her romance with a rebel.

Unlike Ayaka, who is uninterested in motorcycle culture, Ryō displays an enthusiasm that rivals that of the male gang members. The contrasting portrayal of these two female characters is best illustrated in the following passage, in which dispassionate Ayaka observes Ryō’s excitement over the gang’s ride out:

While we were walking back to the shed from the restaurant Misuzu’, Ryō was obviously excited. Her eyes were bloodshot and she was speaking passionately about something. It was probably something about motorcycle riding techniques and engine structures, but I didn’t really understand what she was saying, so I just smiled and nodded while she talked away.[21「「みすず」から歩いて倉庫に戻る間、リョウさんはやっぱ興奮してるみたいで、血走った目で何かを熱く語ってた。多分言ってるのはバイクの運転技術やエンジン構造の話なんだろうけど、あたしにはよくわかんなくてとりあえず愛想笑いしながら相槌だけ打っておいた。」]

(Yū 2009a, 202)

Ryō’s position as one-of-the-boys is further emphasised by her financial and social independence, which further polarises the two characters. Unlike Ayaka, who chooses to be financially and socially dependent on Ryūki, Ryō is not married and has a full time job that gives her financial independence. Her independence can be interpreted as a form of rebellion against normative Japanese society, which encourages women to find a spouse and become a housewife and mother. Furthermore, Ryō’s association with the Yajū gang after her retirement also indicates that she continues to rebel against society in her post-adolescence (as she is in her twenties). Although Ryō and Ayaka are polar opposites, there is no direct conflict or tension between the two within the text: Ayaka repeatedly express her admiration for Ryō, while Ryō takes on the role of a caring and experienced older sister for Ayaka. At one point, Ryō even lends Ayaka her old tokkōfuku, which she has kept as a memento, and this gesture symbolises the sisterly bond they form within the male-oriented motorcycle culture (Yū 2009a, 88). Although Ayaka is part of the pre-existing convention created within the male-oriented yankī narrative, and is thus depicted as a subjugated heroine, her admiration for Ryō hints at her desire for independence and equality. Yet, as a damsel-in-distress, Ayaka ultimately perpetuates the idea that girls need to be rescued and protected by their male partners.

In a way, Ryō also perpetuates hegemonic masculinity, because she is only empowered when she assumes a masculine role. However, her gender performance throughout the text indicates that being a bōsōzoku is only part of her identity, as she retains feminine signifiers. For example, since stepping down as leader of the gang, Ryō rides in her mini skirt rather than tokkōfuku, and she is described by the narrator-protagonist as having beautiful long hair, perfect makeup and an attractive figure (YÅ« 2009a, 87). In addition, Ryō is depicted as a charismatic and capable leader, not only to Ayaka but also to the other male members of the Yajū gang, as she continues to give advice and support to the gang even though she has retired. However, although Ryō’s rebellious identity is modelled on male bōsōzoku instead of redīsu (who are subordinate to bōsōzoku), her rebellion is not dependent on or defined by her relationship with the boys, as is Ayaka’s.

Those studying female rebellion in fiction, such as Medovoi and Caponegro, focus on sexuality and even suggest that sexuality can also be power, using Hal Ellson’s novel Tomboy [1950] as an example, where the tomboy heroine ”withholds sex to maintain her power” within the gang (Caponegro 2009, 320). However, at the same time, sexuality can also be a vulnerability, as once the heroine dates one of the boys, she risks losing her position within the gang and ”being passed on to another and another boy”, just like other girls (Ellson 1950, 34). Thus, the protagonist guards her body by withholding it from the boys. In Tomboy, the rebellious heroine laments being a girl as she is aware of the fact that no matter how much of a masculine identity she may adopt, her feminine body is what separates her from the rest of the gang and she will never really be one of the boys. She complains that ”[a] boy can do everything. Girls can hardly do anything” (Ellson 1950, 24).

Contrary to rebellious heroines in post-1950s American literature, Ryō’s status or power within the gang does not derive from her sexuality, but rather from her riding skills and knowledge of motorcycles, her charisma and ability as a leader. From the perspective of the protagonist, Ryō is depicted as being able to do everything’ the boys are doing. In other words, her femininity does not hinder her from performing a bōsōzoku identity. Although Ryō is only a peripheral character in the Wild Beast series, the number of female characters like her in mobile phone novels has slowly risen. Many works now feature onna sōchō and female bōsōzoku as protagonists, such that these terms have become keywords writers and readers use on sites like Magic i-land and Wild Strawberry to categorise female yankī narratives.18 The presence of Ryō in the Wild Beast series and the growing portrayal of female bōsōzoku within mobile phone novels indicate how yankī culture is being reimagined by girls in mobile phone novels.

Exploring intertextuality in shōjo literature, Aoyama and Hartley (2010) argue that for Japanese female writers, both professional and amateur, borrowing texts is less about passive referencing than it is about creating a ”framework for girls’ creative desires” (6). Indeed, for female mobile phone novel writers like Yū, borrowing yankī elements within the text is not a mere reference to rebellious youth culture as these borrowed elements are redefined in the work, most notably through characters like Ryō. Interpreting the use of yankī elements in the Wild Beast series simply as a revival of decades-old yankī culture hence trivialises the role girls play in the cultural production of such mobile phone novels.

CONCLUSION

Central to Hayamizu’s argument is the parallel between the rebellious girls of the 1980s sharing their real’ tragic stories in teen magazines and the tragic love stories girls are now writing and reading on their mobile phones. His argument seems to assume that girls began sharing stories for the first time in the 1980s, when in fact Japanese girls have long been sharing stories in the form of letters and essays in girls’ magazines (Katsuno and Yano 2002, 222).

Instead, what links yankī culture and mobile phone novels is the actual borrowing of yankī elements within the text. The writers and readers of mobile phone novels are estimated to be in their teens or twenties, so their recognition of yankī identities is based on an imagined nostalgia created via their consumption of popular media. Authenticity’ for them stems from the fictional portrayal of rebellious boys as charismatic bad boys with hearts of gold, rather than as problem youth of the 1980s. The glorification of rebellious boys and their portrayal as positive rebels, as well as references to bōsōzoku, indicate that girls have borrowed heavily from tales of teenage rebellion in Japanese popular media rooted in 1980s yankī culture. By replicating existing conventions of the yankī narrative such as the damsel-in-distress and the glorification of male rebel heroes, mobile phone novel writers might be said to simply be perpetuating tropes of male hegemony. However, at the same time, closer examination of this borrowing illustrates that the girls have rejected gender-specific terms like redīsu and sukeban, reimagining bōsōzoku as their own. This selective borrowing and adaptation indicates a desire to challenge the embedded gender hierarchy within yankī culture.

Yet, both Hayamizu and Honda overlook these textual references to yankī culture and as a result trivialise the role girls play in mobile phone novels. Aoyama and Hartley (2010) argue that girls’ cultural production in Japan exposes ”the voice of the girl subjugated within the masculine text” (6), and indeed mobile phone novel writers like Yū remind us how the yankī narrative in the mainstream media is male-oriented. Using UCC sites like Magic i-land and Wild Strawberry as a platform, writers borrow from existing conventions but use them only as a framework on which to project their desires, creating their own yankī narrative. Calling this process a simple revival’ significantly undermines the dynamic role girls play in the cultural production of mobile phone novels.

For generations, girls have borrowed from other texts and created ”the exclusive shōjo world within” that is shared by the writer, the protagonist and the reader (Aoyama 2005, 57). Through the format of UCC, which allows writers and readers to interact with each other directly, mobile phone novel readers, along with the writers, are reimagining yankī culture and creating their own shōjo fantasy world, whereby they can vicariously enjoy the thrills of teenage rebellion and temporarily escape from the marginalisation imposed by a persistently patriarchal society as they scroll through web pages on their mobile phones.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- While the majority of those writing and reading mobile phone novels are teenage girls, some studies indicate women in their twenties are also taking part (Hjorth 2009, 23). As such, the term girls’ is used in this paper to refer to consumers of mobile phone novels as a whole. ↩

- The Wild Beast series was initially published as an online mobile phone novel in 2008—2009, but following its success it was published in print form by Starts Publishing Corporation, in 2009—2010. This paper uses the print publication as the online version is no longer available; all translations are the author’s own. ↩

- Tohan Corporation (Tohan Co., Ltd) and Nippon Shuppan Hanbai Inc. (Japan Publication Sales Co., Ltd), two of Japan’s prominent publication distribution companies, release weekly, monthly and annual top ten bestselling book lists. Tohan Corporation’s annual top ten bestselling book list for the period of December 2005 to November 2006 included four mobile phone novels and series: Koizora (Sky of Love; 2005) by Mika; Tenshiga kureta mono (Gift from an Angel’; 2005) and Line (2006) by Chaco; and Tsubasa no oreta tenshitachi (Angels with Broken Wings’; 2006) by Yoshi (Mizukawa 2016, 61). These works were all initially published online, but following their success were later published in print form. ↩

- The practice of amateur writers publishing their own work is not a new phenomenon in Japan. The history of dōjin (同人) culture, or amateur culture, shows how amateur writers and manga artists in Japan have produced and often circulated both original work and fan fiction since at least the late nineteenth century. For further discussion, see Nicolle Lamerichs (2013). ↩

- This paper—originally presented at Tokyo University of the Arts, at the Cultural Typhoon conference, 2 July 2016—was developed from one of the chapters of my PhD thesis ”Ochikobore Seishun Shōsetsu: The Portrayal of Teenage Rebellion in Japanese Adolescent Literature” (University of Auckland 2016). ↩

- Yoshi claims to be the ”father of the mobile phone novel” (ケータイ小説の生みの親) on his website (Yoshi Official Web 2017). Although he was indeed one of the first, the early work of writers such as Mika and Chaco also played a crucial role in the development of the genre. Yoshi’s claim also ignores the contribution his readers made by sending him their own stories and experiences, which were incorporated into his first bestseller, the Deep Love series (Honda 2008, 36). ↩

- Ochikobore seishun shōsetsu’ is a term I have proposed to refer to juvenile delinquent novels in Japanese adolescent literature. For a detailed discussion on the decision to use the term ochikobore (おちこぼれ; dropout) instead of furyō’ or yankī’ (both meaning delinquent), see Kim (2016, 3—10). ↩

- While the term furyō’ is a generic term for a wayward teenager, yankī’ is associated with a specific time and subculture. The subtle difference between the two is usually lost in English as they are both translated as rebel’ or delinquent’. ↩

- An alternative theory is that the term yankī’ comes from Japanese dialect, arguing that the suffix –yanke(やんけ), which was frequently used by Japanese delinquents in the 1980s, morphed into yankī’ (Nanba 2009, 6). ↩

- In an earlier comparative study of youth culture research, I conclude that an increase in adolescent population and economic prosperity seem to be the key factors that contribute to the creation of youth culture (Kim 2016, 13—29). ↩

- In a personal conversation on 16 November 2012 with Japanese author Natsuki Endō, who had been a bōsōzoku leader in the 1980s, Endō explained that the term tsuppari’ comes from the verb tsupparu (突っ張る; to be defiant), which was used to categorise rebellious students in the late 1970s. They rebelled specifically against school authorities and performed their rebellion by customising their school uniforms and breaking other school rules. ↩

- The glorification of yankī through positive portrayal in 1980s films was similar to the way yakuza were portrayed in ninkyō eiga (任侠映画; chivalrous yakuza films) of the 1960s. Unlike the later yakuza films, such as Jingi naki tatakai (Battles Without Honor and Humanity; 1973), yakuza in ninkyō eiga were depicted as moral men who lived and died according to an honourable code of conduct. For more on yakuza films see Mark Schilling’s The Yakuza Movie Book: A Guide to Japanese Gangster Films (2003). ↩

- The term good bad boy’ was first coined by Leslie Fiedler (1960) regarding American literature. Fiedler differentiates rebellious characters who, despite being labelled as delinquents or dropouts by society, know right from wrong, as opposed to more villainous teenage thugs. ↩

- Rontai’ (ロンタイ) is derived from the English long and tight’, and during the 1980s it became a slang term for the long and tight skirts Japanese girls were wearing at the time. ↩

- The success of films like Kurōzu zero (Crows Zero; 2007) (based on the 1990s manga Kurōzu (Crows; 1990—1998)), and manga like Samurai sorujā (Samurai Soldier’; 2008—2014) and OUT (2012), illustrates how yankī narratives have continued to thrive in popular media even when yankī culture has become outmoded in the streets and replaced by more recent types of teenage rebel culture, such as the karoā gyangu (カラーギャング; lit., colour gangs’) of the late 1990s or chīmā (チーマー; lit., teamers’) of the 2000s. Nanba categorises these more recent types of rebellious youth culture as ”neo-yankī” (ネオヤンキー) (Nanba 2009, 191—95). ↩

- Lolita’ is a fashion subculture that emerged in the late 1990s, in which girls dress up in clothing inspired by the Victorian and Edwardian eras. The name is derived from the promiscuous young female character in the novel Lolita (1958) by Vladimir Nabokov. ↩

- Comment made by Natsuki Endō in an interview with the author, 16 November 2012. ↩

- A search on the combined terms onna sōchō’ and bōsōzoku’ returned 7,252 stories on the Magic i-land search engine, and 965 stories on Wild Strawberry (results as of 12 January 2016). ↩