Straddling the Line: How Female Authors are Pushing the Boundaries of Gender Representation in Japanese ShÅnen Manga

Published July 02, 2018

Pages 76-97

https://doi.org/10.21159/nvjs.10.04

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney and Daniel Flis, 2018

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

New Voices

in Japanese Studies

Volume 10

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2018

Abstract

This paper will show the ways in which authors of shōnen (boys’) manga can offer representations of gender performance that depart notably and significantly from the conventional framework which characterises many shōnen manga works (the shōnen framework’). It does this through a comparative analysis of gender performance in two shōnen manga series: Noragami [2010—], by female author duo Adachitoka, and Akame ga Kill! [2010—16], by male authors Takahiro and Tetsuya Tashiro. The paper seeks to demonstrate how the authors of Noragami have been able to subvert the gendered framework of shōnen manga while still writing within the genre. Examples of non-conventional gender performance in the female-authored work include resistance to gendered power dynamics and parody of traditional gender roles. These departures do not always reject the shōnen framework altogether, but instead present new ways for gender performance to be represented within it. In straddling the line between conforming to and subverting shōnen tropes, Noragami shows the potential for texts to shape and contest ideas about gender identity within a genre that is still dominated by hegemonic masculinity.

INTRODUCTION

This paper is interested in the intersection of gender and popular culture in Japan, and specifically, representations of gender in Japanese manga. In this discussion I demonstrate how two female authors of contemporary shōnen (少年; boys’) manga have been able to portray representations of gender which are non-conventional in the genre while still remaining successful in the market. To show how this is achieved, I will analyse and compare the images and language of two shōnen manga texts with similar target readerships. Firstly, I will examine the male-authored shōnen manga series Akame ga Kill! (アカメが斬る! [Akame Kills!’]; 2010—2016) as an example of how shōnen manga is written when conforming to the commonly used framework for gender performance in the genre (the shōnen framework’).1 Secondly, I will analyse the female-authored shōnen manga series Noragami (ノラガミ; 2010—) to reveal how it straddles the line between conforming to and subverting the shōnen framework, thus opening up new ways for gender to be represented in this context.

Japanese manga has seen a surge in global popularity in recent years (Alverson 2017). It would be unusual to enter a Western comic book store in 2018 and not find a dedicated Japanese manga’ section showcasing a diverse range of titles. In Japan, manga is marketed and sold in four distinct genres: shōnen (boys’), shōjo (少女; girls’), seinen (青年; young men’s) and josei (女性; women’s) manga (Matanle et al. 2014, 475). These genres are named to correspond with the assumed gender and age of their target readers, and the characters represented within ”are likely to reflect the characteristics of the desired readership” (Ueno 2006, 16). This has given form to a framework which influences the way gender is commonly represented within each genre. For example, the shōnen manga genre is so named because it is targeted at boys in their late teens; as such, its content is commonly intended to appeal to boys at an age where they typically undergo puberty and develop romantic and sexual interests (Jones 2013). Shōnen manga often offers up simplistic heteronormative narratives centring on a male protagonist who ”goes through multiple trials and setbacks as he ventures on to a bright and glorious future” (Ingulsrud and Allen 2010, 13). The gendered framework in shōnen manga ensures that the male protagonist exemplifies hegemonic masculinity’ as understood by R. W. Connell (2005): he acts in ways which legitimise the dominant position of men in society and justify the subordination of women.2 On the other hand, female characters in this genre are relegated to supporting roles and/or sexualised (Ito 2000, 10—11).

Until the 1990s, there were very few shōnen manga series written by women. However, over the last few decades, female authors of shōnen manga have become more common and their works often reach a mainstream audience. Popular examples include Rumiko Takahashi’s Inuyasha (犬夜叉; 1996— 2008), Hiromu Arakawa’s Fullmetal Alchemist (鋼の錬金術師; 2001—2010) and Shinobu Ōtaka’s Magi (マギ; 2009—2017). During this time, the female readership of shōnen manga has also been on the rise (”Hakkō busū” 2012). This paper is interested in the phenomena of female authors writing popular works for a genre which is targeted primarily at young males, and how these authors can challenge perspectives rooted in hegemonic masculinity. While challenges to stereotypical gender representations can come from any author, regardless of their gender, this paper draws inspiration from feminist standpoint theory which holds that ”only women’s perspective[s] can open up epistemic space to radically reorganise the gendered relations of domination in society” (Cattien 2017, 8). From this position, I argue that female authors writing in the shōnen genre are more likely to critique or subvert the dominant gendered framework than male authors.3 My aim is to explore one example of how female-authored shōnen manga has been able to loosen the genre’s rigid gender framework and create spaces within it which allow for a greater variety of gender performances.

The Shōnen Framework

Manga with a male target readership, including shōnen and seinen manga, has long been criticised for its exploitative and oppressive representations of women. One of the earliest comprehensive studies of gender representations in shōnen manga was Kinko Ito’s (1994) analysis of thirty-one weekly shōnen manga comics from 1990 to 1991. Ito found that, in most stories, the female characters are bystanders—if they exist at all. Anne Allison (1996) remarks that ”sexuality is heavily imbricated with violence in Japanese comics” (71), and Susan Napier (1998) criticises the depiction of women and girls in manga as representing negative stereotypes. While these criticisms date back to the 1990s, when English-language manga scholarship was first emerging, they still apply today. In a 2013 study of four twenty-first century shōnen manga series, Hattie Jones finds that shōnen manga still ”reflect[s] a lack of understanding about the [female] sex” (73). These representations of female characters are evidence of what I propose is the gendered framework of the shōnen manga genre. The shōnen framework restricts the genre’s capacity to represent gender performances in two key ways: by inviting the male gaze, and by portraying female characters as Good Wife, Wise Mother’ (良妻賢母; ryōsai kenbo) archetypes. In doing so, it ensures that shōnen manga appeals to its male readership through narratives rooted in hegemonic masculinity.

John Berger’s insights into female representation in visual art underpin my examination of the male gaze in shōnen manga. While the term male gaze’ was coined by Laura Mulvey in 1975, Berger highlighted the phenomenon in 1972 by showing how some European oil paintings invite viewers to perceive female subjects as primarily sex objects. Operating in this way, a work that adopts the male gaze can be seen as assisting the perpetuation of hegemonic masculinity. Additionally, the preference for the Good Wife, Wise Mother archetype in the shōnen framework limits the possible representations of female subjectivity in shōnen manga. The Good Wife, Wise Mother is a model of femininity that began as a nineteenth-century education project (Inoue 2002) and still persists as an ideal in the minds of many Japanese (Koyama 2013). I argue that these two elements are the central pillars of the shōnen framework, which Akame ga Kill! conforms to and Noragami subverts.

Through my analysis of the male-authored shōnen manga series, Akame ga Kill!, I will show how the shōnen framework influences the way male and female characters perform their gender on the page. Against this, I will then show how the female-authored shōnen manga series, Noragami, is able to adhere to aspects of the shōnen framework while simultaneously challenging them through its characters’ gender performances. Noragami is a contemporary example of a female-authored shōnen manga series which is able to further loosen the rigidity of the shōnen framework and open the way for greater representation of gender performances in mainstream manga.

Akame ga Kill! and Noragami

Akame ga Kill! and Noragami have many similarities that make them eligible for comparison. Both titles were serialised in shōnen magazines, followed by tankōbon publications and anime adaptations due to their popularity.4 Both titles began serialisation within a year of each other and exist within the same sub-genre of fantasy action/adventure. Due to these similarities a significant crossover of target readerships is likely, making these titles suitable for an analysis of the gendered framework in shōnen manga. A further reason why these series were selected was their characters’ gender ratios. Both Akame ga Kill! and Noragami centre on a male character, which is standard for shōnen manga. However, both titles also feature a large cast of female characters, which is atypical for the shōnen genre.5 As Unser-Schutz (2015) found, it is still common in shōnen manga for male characters to number over 80% of the total (142), and for male characters take up the majority of the dialogue on the page (141). Because Akame ga Kill! and Noragami each feature a wide range of prominent female characters, they offer an opportunity to analyse the treatment of both male and female characters by authors of both sexes within the shōnen manga framework.

Akame ga Kill!

Akame ga Kill! is a shōnen manga series written by Takahiro (タカヒロ) and illustrated by Tetsuya Tashiro (田代 哲也), who are both male.6 It was serialised in Square Enix’s Gangan Joker (ガンガン JOKER) magazine from March 2010 until December 2016, and was adapted into a 24-episode television anime series which aired in 2014. The series title refers to one of the main characters, Akame, describing her as one who ”kills”. More specifically, the Japanese characters used for ”kill” (斬る; kiru) denote the specific meaning of killing a human with a bladed weapon, as Akame does throughout the series.

As the name suggests, Akame ga Kill! is billed as an action manga. Almost every chapter contains bloody and visceral battles between a team of assassins called Night Raid and members of a corrupt government and military. The story begins with Tatsumi, a brown-haired warrior in his mid-teens, who arrives at the capital of a fictional country in search of a job in order to send money back to his poverty-stricken village. On Tatsumi’s first day in the capital he meets Leone, a buxom, blonde-haired young woman who swindles him out of all his money. Tatsumi is sleeping on the streets when he is taken in by a wealthy family, but the next evening Night Raid attacks their mansion and kills the family. Tatsumi, who tries to defend the family that sheltered him, becomes engaged in combat with Akame, a sword-wielding, black-haired female fighter around Tatsumi’s age. Akame is the superior fighter and is on the verge of killing Tatsumi when Leone emerges and stops her. Leone then reveals why the noble family was targeted by Night Raid: they were known to capture and torture people for their own amusement and would have done the same to Tatsumi had Night Raid not intervened. Leone feels guilty for taking Tatsumi’s money, and upon seeing that he is a talented fighter invites him to join Night Raid. The series then follows Tatsumi and the other members of Night Raid as they work to overthrow the corrupt government that has brought poverty and strife to the nation. Akame ga Kill! appeals to its male readership by perpetuating notions of hegemonic masculinity and by sexualising its female characters, and as such follows the general shōnen framework.

Noragami

Noragami is a shōnen manga series created by Adachitoka (あだちとか), a pen-name which is a combination of the surnames of Adachi, the character artist, and Tokashiki, the background artist, who are both female. It was serialised in Kodansha’s Monthly Shōnen Magazine from December 2010 but has been on hiatus since May 2017 due to the authors’ ill health and therefore is presently unfinished (”Noragami Manga” 2017). Noragami was also adapted into two television anime series called Noragami and Noragami Aragoto in 2014 and 2015, respectively. The series title combines the words nora’ (野良), meaning stray’ and ~gami’ (the suffix form of kami’; 神) meaning god,’ in reference to Yato, the male protagonist of the series. Although Yato is a god, his ”stray” label denotes him as a lowly wanderer and also as someone who may change his loyalties at any time.

Noragami tells the fictional story of Yato, one of Japan’s lesser-known gods, and a human girl, Hiyori Iki, who is able to leave her body and exist as a spirit. In the tale, Japanese gods are portrayed as answering the prayers of their shrine patrons when given a five-yen tribute. As Yato does not have a shrine of his own, he takes up odd-job requests for a fee of five yen. Calling himself the ”Delivery God” (デリバリーゴッド), Yato advertises his services by writing his phone number on public walls. While he is carrying out a job for a client, a chance encounter with Hiyori intertwines their fates and Yato accepts Hiyori’s request to help prevent her spirit from being able to leave her body. As a shōnen manga series, Noragami conforms to some of the elements in the shōnen framework while challenging others through a variety of means, including giving autonomy to female characters and subverting the Good Wife, Wise Mother archetype.

Gender and Power

Female characters in shōnen manga are often represented as bystanders (Ito 1994) or sexual ”commodities” (Jones 2013, 35). This form of representation invites the reader to regard female characters as merely secondary to the male protagonist, or as little more than sexual objects. This approach has been shown to be successful with the genre’s target readership: in 1968, Weekly Shōnen Jump ”became an instant hit” when it launched with serialisations such as Gō Nagai’s Harenchi Gakuen (ハレンチ学園; 1968—1972), which depicted male characters ”catching glimpses of girls’ panties or naked bodies” (Ito 2005, 469). This style of sexualisation has been used in shōnen manga over the last half-century and has become a consistent part of the shōnen framework.

These problems of gender and power are hardly unique to Japan. Commenting on the sexualisation of women through visual representation in European oil paintings, John Berger stated that ”men act and women appear. Men look at women” (1972, 47; emphasis original). In describing the phenomenon of women in Western films being depicted as objects of male pleasure, Laura Mulvey noted that ”pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its fantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly” (1975, 11). The ”active/male” and ”passive/female” elements of the male gaze are very common in shōnen manga. Anne Allison describes the male gaze in shōnen manga as containing three elements: ”gender (men look, women are looked at), power (lookers are empowered subjects, the looked at are disempowered objects) and sexuality (looking produces one’s own sexual pleasure, being looked at produces another’s sexual pleasure)” (Allison 1996, 31). As mainstream shōnen manga series, both Akame ga Kill! and Noragami reproduce the male gaze in some way. This typically involves sexualising female characters outside of the narrative context, a practice often referred to as fan service’ (Brenner 2007, 88—92). In shōnen manga, fan service’ typically takes the form of illustrations of female characters that allow the reader to peer up skirts or focus upon breasts, without the characters being privy to the reader’s exploitation. Further, it often involves scenes that are irrelevant to the story. For this discussion I will draw on two examples of fan service in Akame ga Kill! in order to demonstrate their invitation of the male gaze within the shōnen framework.

The Male Gaze in Akame ga Kill!

In Akame ga Kill!, illustrations of female characters wearing revealing clothing, undressing and bathing are all used to appeal to the intended heterosexual male reader. The two examples I will outline in this section involve the male protagonist Tatsumi (and the reader) looking at the semi-exposed bodies of female characters. The first example shows the titular female character Akame undressing in front of Tatsumi while seemingly unaware of the sexualisation of her body. In Chapter Three of the series, Tatsumi goes with Akame to gather food for Night Raid, whereupon Akame leads him to a lake to hunt for giant tuna. When arriving at the lake, Akame begins to undress. While this initially startles Tatsumi, he appears dejected when it is revealed that Akame is wearing a bikini under her clothes, implying he had hoped that Akame’s motive for undressing was sexual. After Akame removes her outer clothing, the reader is given a close-up shot of her bikini top, followed by a full-body shot (Fig. 1). Akame seems at ease while undressing in front of a boy around her age and seems completely unaware that her actions could be interpreted as sexual. In the frame containing the full-body shot, Akame’s words and expressions show no sign of awareness regarding Tatsumi’s reaction to her sudden undressing. Akame is framed so that the she is looking directly at the reader, which—when accompanied by a passive expression that is, ironically, not uncommon for her character—shows her as non-threatening and submissive to the male gaze. Further, Akame’s body is hyper-sexualised by the onomatopoeic description ” fyon“ (ふょん) which appears in the frame where her chest is shown, implying that her breasts made a soft, spring- like sound when she removed her top. Onomatopoeia is used liberally in manga to describe everyday sounds (Miller 2004, 321); by ascribing sound to Akame’s breasts in this way, Akame ga Kill! continues a manga tradition that normalises the sexualisation of women’s bodies. This scene speaks directly to the intended heterosexual male readership of shōnen manga by reaffirming Tatsumi’s hegemonic masculinity as the source of the male gaze.

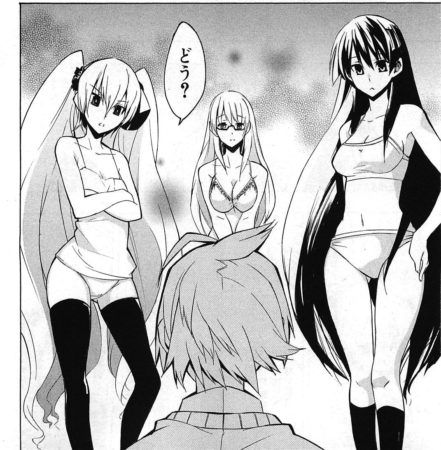

In this scene, Akame is shown to exert some agency over her body because she initiated the undressing, but she has no control over its sexualisation in others’ eyes. Akame ga Kill! also contains scenes where the sexualised bodies of female characters are revealed to Tatsumi and the reader without the consent of those characters. One example of this is a scene in Chapter Seven, in which Tatsumi inadvertently sees the near-naked bodies of three female comrades without their knowledge. The scene involves a magical item called a teigu (帝具; imperial tool’), which Tatsumi tests in Night Raid’s hideout. The teigu takes the form of a headpiece with a large eye on the front, which imbues the wearer with certain sight-related abilities. The members of Night Raid are aware of most of the teigu’s powers, including granting foresight to the wearer and creating illusions, but are unaware that it also has the power to see through solid objects. When Tatsumi dons the headpiece, it activates and allows him to see through his female comrades’ clothes, showing them in their underwear (Fig. 2).

The three female characters in this scene are given no agency over their bodies as they become subjected to the male gaze. This scene explicitly activates the gendered power dynamic of the male gaze (active/male and passive/female) by showing the female characters as unaware of the way that Tatsumi sees them. The female characters’ obliviousness to their exposure is shown by the girl on the left in Figure 2, Main, asking Tatsumi ”Well?” (どう?). Then, in Figure 3, the background text to the left of Main’s head reads ”What’s up with him…?” (何コイツ)) and Akame, on the right, has a question mark drawn next to her head. However, while the characters themselves are portrayed as oblivious, Main’s actions can be read as an indifference to, or even indulgence in the situation. When Main asks Tatsumi ”Well?”, this acts to both explicitly ask him if the teigu is working and implicitly to ask the reader if they like what they see. After this, Main leans forward when her question is not answered, demanding: ”What’s wrong with you?” (どうしたのよ; Fig. 3). The strongly feminine sentence final particle ”no yo“ emphasises her femininity and submission to the male gaze (see Hiramoto 2013, 60—61). In leaning forward, she further exposes herself physically, giving Tatsumi and the reader a better angle to peer down her singlet. Main’s position in Figure 3 brings to mind the words of John Berger: ”It shows her passively looking at the spectator staring at her naked. This nakedness is not, however, an expression of her own feelings; it is a sign of her submission to the owner’s feelings or demands” (1972, 52). It is in this way that Akame ga Kill! appeals to the power of the male gaze, by giving Tatsumi ownership of the female form.

This scene exemplifies the gendered power dynamic in the male gaze as Tatsumi’s description of the teigu becomes an analogy for the way shōnen manga uses the male gaze without consequence: ”What a wonderful ability…! This teigu is amazing…” (なんだこの素晴らしい能力は… 帝具ってスゲ. In much the same way as shōnen manga uses the male gaze, the teigu gives Tatsumi (and readers) the power to look upon women’s bodies with impunity. Beyond his role as a passive observer, as in the previous scene when Akame undressed, Tatsumi becomes an active and willing consumer of the women’s bodies, describing the power to do so as ”amazing”. While Tatsumi makes no specific mention of his own sexual pleasure, the framing of the final panel places readers in Tatsumi’s position, thereby inviting them to join in his voyeurism. The two scenes described above appear in early chapters (Three and Seven, respectively), with many similar scenes present throughout the series’ eighty chapters. Akame ga Kill!’s use of the male gaze is an example of how gender representation is commonly framed in the shōnen genre. The next section shows how the female-authored Noragami contains fewer instances of the male gaze, and how these are used reflexively to problematise the typical gender dynamics of the shōnen framework.

Female Bodily Autonomy in Noragami

While Noragami contains far fewer instances of the male gaze than Akame ga Kill!, the central female character is still sexualised. There are intermittent instances throughout the series of the aforementioned fan service’, which invite the male gaze by allowing the reader to see up Hiyori’s skirt or showing her bathing. However, these occurrences are often brief and unfold without the presence of a male character. One notable exception comes in Chapter Twenty-five of Noragami, in which Hiyori’s physical body is controlled and exploited by Yato. This scene not only appears noticeably later in Noragami than similar scenes in Akame ga Kill! (showing how much more frequently Akame ga Kill! invites the male gaze), but it also differs greatly in tone. Unlike the previous examples from the male-authored Akame ga Kill!, the female-authored Noragami does not show Hiyori (the object of the male gaze) as being oblivious to her sexualisation; rather, it shows her as being fully aware of her objectification and gives her a voice with which to protest against it. In this way, Noragami strikes a skilful balance between fitting the criteria of the shōnen framework, yet simultaneously disrupting the power of this entrenched element of the genre by challenging the idea that female characters are only passive objects for male consumption.

In Chapter Twenty-five, the series takes a break from the primary narrative to present what appears to be an offshoot episode in which Yato uses his power of ”divine possession” (神憑) to take control of Hiyori’s body. This involves forcibly removing Hiyori’s spirit from her body, thereby allowing Yato to take full control. Yato spends the day in Hiyori’s body at her school, promoting his ”delivery god” business by flirting with her classmates and teachers and giving up-skirt shots to them. Like the teigu in Akame ga Kill!, Yato’s divine possession becomes analogous with the male gaze: it permits Yato full control over Hiyori’s physical body, which he unhesitatingly sexualises for personal gain. Yato’s explanations for taking control of Hiyori’s body are varied and inconsistent, and mostly function to add comedy or drama to the scenes. At first, he positions his actions as a comical response to Hiyori’s comment that she ”wants to be together with Yato more” (もっと夜トと一緒にいたい). However, he later claims that the motive was to advertise his business, and again separately states that he was aiming to win Hiyori’s affections.

The divine possession scene begins with Yato seemingly boasting about his power to control Hiyori’s body, addressing the readers directly as Hiyori and placing one leg on a table to reveal her underwear (Fig. 4). The real Hiyori—who is depicted to the left in spirit form—is noticeably embarrassed by this act, as denoted by her blushing face. This scene is followed by a montage of Yato (as Hiyori) interacting with male students and teachers in Hiyori’s school, in which he acts out the female role in many stereotypical male fantasies found in shōnen manga (such as asking to be carried somewhere by a male student, sitting on a male teacher’s lap, and confessing her love’ for a group of older male students). In these scenes, the authors appear to demonstrate an awareness of how female characters are subjected to the male gaze in shōnen manga, using parody to ”transform existing inequalities and potential threats into pleasure and gratification [for the reader]” (Aoyama 2012, 66). This gratification comes from the humour derived from a male character (in a female form) behaving in the way women are expected to in shōnen manga. During these scenes, Hiyori is denied autonomy as per the shōnen framework, but the authors compensate for this by giving her a voice through which she can object to the way her body is being controlled. In every instance in which Yato reveals Hiyori’s underwear, either inadvertently or deliberately, Hiyori is there to voice her discomfort. In Figure 4, the spirit Hiyori shouts her objection to how Yato has positioned her leg, letting her classmates and the reader see up her skirt: ”[My] leg!!” (足いー!!). In another frame she yells: ”Cover it up a little!!!” (ちょっとは隠しなさぁーい!!!).

While the divine possession scene grants Hiyori a voice with which to object, shouting her opposition does nothing to stop Yato from controlling her body. Even though she physically fights back against Yato in an attempt to make him surrender her body (Fig. 5), Yato is able to flee from her and causes more mischief. When Yato eventually relinquishes Hiyori’s body, it is not because of Hiyori’s objections, but because he dislocates her shoulder and cannot endure the pain. Hiyori’s objections to how her body is treated gives her no true autonomy in these scenes, and therefore highlights the power imbalance inherent in the male gaze, between those who look and those who are being looked at.

The divine possession scene represents one of the ways in which Noragami parodies the stereotypical gender roles that are representative of the shōnen framework. Through the male gaze, the male becomes an active viewer of the female body, and the female becomes a passive object for his consumption. This is a relationship of power and control whereby the male manipulates the female form in order to fulfil his desires. Akame ga Kill! represents this control through Tatsumi’s use of the teigu, and Noragami does so through Yato’s power of divine possession’. Through these narrative devices, both series draw on metaphors of supreme power (imperial’ and divine’), positioning the male gaze as a right that comes with the territory of inherited or inherent power and thereby conforming to the shōnen framework. However, in Noragami, Hiyori’s behaviour in actively trying to end her objectification is contrary to the submission and acceptance shown by the female characters in Akame ga Kill! Within the Noragami narrative, Hiyori acts to reject Yato’s control over her body, while on a meta-narrative level, the authors parody the way that the male gaze is typically used to objectify women in shōnen manga.

The Good Wife, Wise Mother in Shōnen Manga

Unser-Schutz (2015) found that shōnen manga uses stereotyped speech more often for female characters than male characters. I argue that beyond just speech, shōnen manga uses stereotyped representations of femininity to inform the way its female characters behave. The primary template that shōnen manga uses to represent femininity is the Good Wife, Wise Mother ideal in Japanese society. When choosing to marry and start a family, many Japanese women have traditionally quit their jobs and lost their economic autonomy (Nakamura 2005; Yamamoto and Ran 2014). Their role in Japanese society then becomes one of support for their husband (the daikoku-bashira’), and one of primary care-giver for their children.7 Even though the term Good Wife, Wise Mother’ may seem anachronistic in twenty-first—century Japan, the ideal it represents remains the prevailing societal expectation for Japanese women (Koyama 2013, 7) and is still regarded favourably by many Japanese men (Hidaka 2010, 94). As a result, the Good Wife, Wise Mother archetype is present in many examples of shōnen manga and can be identified as part of the shōnen framework.

Conforming to the Good Wife, Wise Mother Norm in Akame ga Kill!

Akame ga Kill! may not immediately seem to be an example of a shōnen manga with submissive or stereotypically feminine characters—after all, most of the female characters found within it are supposedly cold-blooded assassins. However, Katharine Kittredge (2014) points out that manga which portrays physically strong female characters often incorporates elements that mark them as fantasy objects for male readers, counter-balancing this strength with ”their heroines’ distinct lack of agency” (512). Kittredge observes that this lack of agency is denoted by the female characters’ relationships with an adult male character (512). In Akame ga Kill!, this manifests in the way that the female characters regress’ from unemotional assassins to kind hearted Good Wife, Wise Mother types when they are around male characters. I describe this as a regression not because kind-heartedness should be seen as a lesser trait, but because the nature of Good Wife, Wise Mother is that of a woman in a subservient position to a man. Thus, the female characters regress from active to passive subjects when the narrative turns them from active fighters into submissive carers for male characters.

In Akame ga Kill!, the series need not show its female characters as literal wives or mothers to imply that it sees them as Good Wives, Wise Mothers. As the titular character, Akame is a good example of this. She assumes the role of Good Wife, Wise Mother in the way she interacts with Tatsumi, and this role manifests early in their relationship. Akame is shown initially to be cold and emotionless due to her assassin training as a child, and she maintains that persona throughout most of the series. The exceptions to this are when the story inexplicably turns Akame into a Good Wife, Wise Mother by showing her as caring or nurturing towards Tatsumi. This then also serves to reinforce Tatsumi’s hegemonic masculinity.

The first scene to reveal this involves Akame and other female members of Night Raid stripping Tatsumi down to his underwear after his first mission. As Tatsumi is shown trying to cover his semi-naked body, it is revealed that by undressing him the others were making sure that Tatsumi was not hiding any wounds beneath his clothing. The members of Night Raid state that it is common for new members to act tough and hide the injuries they receive on their missions. Upon seeing that Tatsumi is unscathed, Akame is seen with a smile on her face for the first time in the series. She then explains that the mortality rate for first missions is high and implies that she was worried about him. This display of care and compassion from Akame is strikingly opposed to her general characterisation as a cold-blooded assassin, but fits with the way that shōnen manga uses female characters as fantasy objects for male readers. Despite years of training to conceal her emotions, Akame’s femininity’ comes out when she is around Tatsumi. Akame may be a sword-wielding cold-blooded assassin, but Akame ga Kill! positions her as a subservient Good Wife to Tatsumi; as Kittredge (2014) points out, her ”distinct lack of agency” (512) marks her as a fantasy object for male readers.

Some scholars have observed an assumption within Japanese society that many gendered traits have a physiological basis. For instance, anthropologist Akiko Takeyama (2005) found that some Japanese people regard the concept of a motherly instinct’ as being an inherent part of female biology. This supposedly biological motherly instinct’ does not necessarily denote a mother-child relationship but is described by some Japanese men as making women ”feel good about their devotion to others, in particular the men they love” (Takeyama 2005, 207). This concept of motherly instinct’ has its roots in the Good Wife, Wise Mother education project of the nineteenth century that ”advocated the traditional virtues and values of ideal womanhood, such as obedience to father, husband, and, later, eldest male child” (Inoue 2002, 397). By this metric, a woman’s worth is measured by her relationship with men; this devalues her professional identity and places greater emphasis on her role as caregiver to the men in her life. In Akame ga Kill!, the Good Wife, Wise Mother characterisation is not limited to Akame. The series contains a large female cast, and almost all of those who interact with Tatsumi (or another male character) are imbued with similar traits in these interactions.

One female character who deserves particular attention is one of the series’ main antagonists, Esudesu.8 In Akame ga Kill!, Esudesu’s portrayal implies that despite her status as a professionally accomplished young woman, the absence of a relationship with a man means that she will never be satisfied. Esudesu is a General in the Imperial Army and is widely considered to be the strongest fighter in the Empire. Ironically, she is also shown to be a hopeless romantic. Despite her numerous military achievements, Esudesu feels her existence to be incomplete without a romantic relationship. Upon returning to the capital after securing a significant military victory, Esudesu is tasked with killing the members of Night Raid. The Emperor allows Esudesu to name the reward she would like to receive upon Night Raid’s eradication. She responds by saying in humble terms, ”I want to try being in love” (恋をしたいと思っております), and requests that the Emperor find her a suitable male partner as her reward. Although such a request could be seen as out of character for someone renowned for their military prowess, the Emperor is unsurprised and implies that he regards it as not unusual for a woman of her age to desire marriage (“将軍も年頃なのに独り身だしな”). This characterisation exemplifies the way that the Good Wife, Wise Mother archetype determines a woman’s worth by her relationship with men while dismissing her professional identity. Akame ga Kill! therefore minimises Esudesu’s military accomplishments and places greater importance on her relationship status.

Echoing the perception that motherly instinct’ is an assumed part of female biology, Esudesu explains that her desire for love is a physiological imperative: ”This, too, is one of those bestial instincts, huh?” (これも獣の本能か). Esudesu eventually falls for Tatsumi and her feelings for him then come to consume her identity. She starts keeping a book close to her in which she draws pictures of Tatsumi and writes down advice she receives from others regarding how to make him fall in love with her. Even while carrying out her duties as a general in the Imperial Army, her thoughts inevitably turn to Tatsumi: ”Against my better judgement, I look for Tatsumi whenever there are crowds of people” (つい人が多いとタツミを捜してしまう). By this admission, Esudesu explicitly states that her obsession with Tatsumi is something that she feels unable to control, which mirrors the lingering assumption in Japan that a woman’s motherly instinct’ is something unconscious and biological.

Despite Akame being a skilled assassin and Esudesu being an accomplished military general (and an implied sadist, no less), the series imbues each of them with the traits of a Good Wife, Wise Mother—even though that this contradicts their dominant character profiles. Both characters only display their Good Wife, Wise Mother side around or in relation to Tatsumi, which then reinforces Tatsumi’s position of power and dominance. Through this, Akame ga Kill! shows the ways in which the shōnen framework dictates how gender identities must be characterised in order to reinforce the subordination of women by hegemonic masculinity. In the next section, I will discuss how Noragami imagines alternative roles for women.

Breaking Free from the Good Wife, Wise Mother in Noragami

Noragami is able to subvert the shōnen framework through its non-stereo- typical depictions of several female characters. These characters challenge common shōnen tropes and reject traditional gender roles. In the story of Noragami there are two worlds: the higan (彼岸; far shore’) and shigan (此岸; near shore’).9 The shigan represents the natural world in which all humans live; however, for Hiyori, it also represents the world in which she feels she is predetermined to become a Good Wife, Wise Mother. Hiyori’s story is therefore about breaking free from a world in which she is pressured to conform to the stereotypes of an assigned gender identity. The reader first learns about the pressure Hiyori feels when she is walking home from school while talking with two female friends. Through their conversation, it comes to light that Hiyori is a fan of professional martial arts and that she is choosing to keep this a secret from her parents. The reason for this is because Hiyori thinks her parents will not approve of her unfeminine’ interest. Hiyori imagines her mother berating her: ”Because you’re a girl, right!?… You will become a lady who won’t bring shame to the Iki family name… And one day you will [get] a fine husband” (あなたは女の子なんですからね!?壱岐家の名に恥じぬよう立派な淑女に…そしていずれ立派な婿君を). Through dialogue, the reader learns that Hiyori’s interests do not conform to a traditional feminine identity and this is seen as problematic by the people around her. However, in the next frame Hiyori states that she disagrees with her mother, saying she thinks her mother (and her ideas on traditional gender roles) is old-fashioned—a point which is underscored by her mother’s language use.10 Hiyori desires to live in a world where she is free from rigid gender constructs. This scene sets the stage for how Noragami subverts the shōnen framework by creating a world for Hiyori to experience greater variety of self-expression.

It is soon after this conversation that Hiyori becomes able to transcend her material world and, as a spirit, interact with the gods and phantoms of the higan. Hiyori’s encounter with Yato occurs alongside the first instance of her spirit being able to temporarily leave her body, giving her a new perspective on the world and her place in it. Hiyori’s spirit form represents her transcendence from the Good Wife, Wise Mother identity imposed on her by her parents and, as an extension of this, by society at large. Hiyori’s new situation initially intimidates her as she feels unsure about the path her life will now take: ”This is bad! I don’t like this” (困ります!こんなの嫌です). However, she soon comes to appreciate the new-found perspective that her breaks from convention offer: ”The scenery I see looks different from usual…This might be fun…” (見える景色もいつもと違うのです。これはちょっと楽しいかも).

In her spirit form, she enjoys greater freedom and power than she has access to in her earthly form. Hiyori is shown leaving her body during school hours and roaming around town. No longer restricted by physical limitations, Hiyori’s spirit form can jump great distances and walk along power lines. With this increase in strength and mobility, Hiyori becomes able to easily replicate techniques performed by the martial artists she often watches. Soon after meeting Yato, Hiyori (in her spirit form) saves Yato from a phantom by replicating one of these techniques. In contrast to the way Hiyori imagined her mother reacting to her martial arts obsession, Yato is grateful to Hiyori for saving him and, as if to repay her for her kindness, soon agrees to assist Hiyori in preventing her spirit from leaving her body. Significantly, this encounter reverses the gender dynamic of stereotypical damsel in distress’ rescue scenes, where a helpless female is heroically rescued by a male and subsequently expresses indebtedness to him. These scenes show how Hiyori’s journey to the higan grants her the freedom to openly express parts of herself she had previously kept hidden and demonstrates the way in which Noragami is prepared to subvert conventional gender roles.

During her time as a spirit, Hiyori comes to meet other characters who also subvert the Good Wife, Wise Mother archetype. Most notable are two female gods, Bishamonten and Kōfuku, who both also proudly destabilise the Good Wife, Wise Mother model. Bishamonten is a tall, slender woman in her early twenties who often wears semi-revealing clothing. Her appearance defies conventional depictions of the Buddhist deity Bishamonten (毘沙門天), who is usually portrayed as a male warrior dressed in armour (Leeming 2002). Kōfuku, meanwhile, has the appearance of a teenage girl with pink hair. Her language use and behaviour befit her image as a teenage girl: she speaks in mostly gender-neutral plain-form’ Japanese while occasionally using feminine sentence-final particles. It is later revealed that the character Kōfuku is the god of poverty (貧乏神; binbōgami), which similarly challenges traditional depictions of this god as a frail old man. In the narrative of Noragami, both Bishamonten and Kōfuku are the heads of their respective households, thereby fulfilling the traditionally male daikoku-bashira role. In contrast, the male character Daikoku, who lives with Kōfuku, is often depicted wearing an apron as a symbol of his domesticity. Daikoku carries out most of the duties around Kōfuku’s house: he serves tea when guests arrive and is often seen cooking and cleaning. Daikoku’s depiction as a tall and muscular man is incongruous with his role as a traditional housewife, thereby allowing him to act as a parody of that stereotype. These reversals of gender roles in Noragami reject the ”conservative, patriarchal view that women’s proper’ place in society is in the home” (Yoda 2006, 267) and open up new ways for gender to be represented within the shōnen framework.

Noragami is thus the story of Hiyori exploring alternatives to the Good Wife, Wise Mother identity by experiencing a world of greater possibilities. However, traditional gender roles are shown to be deeply ingrained in Hiyori’s character and she risks returning to her old life if she does not actively choose to remain in the higan. After spending some time as a spirit, Hiyori eventually returns to her body and becomes reindoctrinated in the gendered customs of the physical world. During this time, her memories of the higan begin to fade; she behaves more like a stereotypical schoolgirl and feels herself again being pushed into a life not of her choosing. Eventually, however, Hiyori is unwilling to give up her new-found freedom and makes the choice to return to the spirit world where she is not expected to conform to a Good Wife, Wise Mother identity. This outcome may be read in two ways. Firstly, Noragami reads as escapist fantasy for Japanese women who feel the need to create a world into which they may escape from their society’s patriarchal tendencies. Secondly, Noragami suggests that, for women in Japan, a life free from predetermined gender roles requires one to be an active agent in determining their own gender performance.

The male-authored Akame ga Kill! depicts its female characters as always being subservient to a Good Wife, Wise Mother identity, even if it directly conflicts with their characterisation. The female-authored Noragami, on the other hand, demonstrates an awareness of how female characters are often written through the lens of this gendered ideology, and allows its female characters to break free from it. Through the depictions of Hiyori, Bishamonten and Kōfuku, Noragami offers more varied representations of femininity than the shōnen framework appears to allow.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have established the conventional ways in which gender is represented in shōnen manga, and have shown how these align with what I call the shōnen framework’. The paper began with an examination of how the shōnen framework is demonstrated in Akame ga Kill! Through the use of the male gaze and the ryōsai kenbo ideal, the framework restricts the genre’s capacity to represent varied gender performances. Despite the dominance of this framework, however, there is potential for its subversion, as shown through my analysis of Noragami. While the focus of this paper has been on using the shōnen framework to demonstrate differences between male and female authors’ approaches to the genre, applications of the genre framework concept may extend to examinations of shōnen manga series’ popularity (within Japan or worldwide), as well as differences in works across generations and genres.

The paper shows how one example of female-authored shōnen manga offers representations of gender performances that depart notably and significantly from the shōnen framework. These departures do not always reject the framework altogether, but instead present new ways for gender to be performed within it. Specifically, I have demonstrated how atypical representations of gender performances, such as those in Noragami, are able to loosen the genre’s strict gender framework. Insofar as can be ascertained from sales figures, it would seem that Noragami’s gender representations have been accepted within shōnen manga’s readership, but further research is required to fully understand the effects that female authors have had on the shōnen genre and its readers. However, Noragami’s broad popularity can be seen as a significant sign that the shōnen framework is changing. Female readership of shōnen manga has seemingly increased over the last few decades and so it may be interesting to consider how female readers experience these works. This would require further research among female readers of shōnen manga in Japan, which is outside the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, establishing Noragami as an exemplar of the way in which female authors of shōnen manga are departing from the genre’s gendered framework is an important first step to understanding how these changes will impact readers.

My comparisons between the male-authored Akame ga Kill! and female- authored Noragami demonstrate how female authors have been able to portray representations of gender which are non-conventional to the genre, yet still remain successful in the market. My analysis has focussed on Noragami’s subversive portrayal of power in gender relationships and its rejection of traditional gender roles. Through these representations of gender performance, I have argued that Noragami has subverted the shōnen framework and created spaces where female characters may be represented in new ways in shōnen manga. As the textual analysis offered in this paper has demonstrated, Noragami has diverged significantly from the simplistic heteronormative gender performances depicted in many shōnen manga works. These, and other departures in other texts, will potentially impact on the ways in which shōnen manga shapes ideas about gender identity in readers.

Glossary

Bishamonten (毘沙門天)

A Buddhist deity usually portrayed as a male warrior dressed in armour

daikoku-bashira (大国柱)

The central pillar of a house or building; also a metaphor for the breadwinner of a family

higan (彼岸)

far shore’; used in Buddhism to refer to the spirit realm

josei (女性) manga

women’s manga (lit., females’ comics)

ryōsai kenbo (良妻賢母)

Good Wife, Wise Mother’; a model of femininity that became entrenched in late nineteenth-century Japan

seinen (青年) manga

young men’s manga

shigan (此岸)

near shore’; used in Buddhism to refer the realm of the living

shōjo (少女) manga

girls’ manga

shōnen (少年) manga

boys’ manga

tankōbon (単行本)

stand-alone book’ of manga chapters, as opposed to those serialised in magazines

teigu (帝具)

lit., imperial tool’; a made-up word that refers to a magical item in the manga, Akame ga Kill!

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- The official title in Japanese is read as Akame ga Kiru!’, but the series’ tankōbon (単行本; stand-alone book’; non-serial manga) publications officially romanise the title as Akame ga Kill!’, which I adopt here for simplicity. ↩

- A comprehensive analysis of hegemonic masculinity is beyond the scope of this paper. For a detailed discussion, see Connell (2005, 77—81). ↩

- An analysis of the debate between proponents and critics of ”feminist standpoint theory” is outside the scope of this For details, see Cattien (2017, 7—9). ↩

- Akame ga Kill! sold 2.1 million tankōbon copies by the release of its tenth volume (”Akame ga Kiru!’ dai-18-wa tōjō” 2014) and Noragami sold 2.2 million tankōbon copies between November 2013 and November 2014 (”Top- Selling Manga” 2014). ↩

- There have been other popular shōnen manga series which centre on a male character and feature a large cast of female characters, including Rumiko Takahashi’s Maison Ikkoku (めぞん一刻; 1980—1987) and Ken Akamatsu’s Love Hina (ラブひな; 1998—2001). However, the plots of these series revolve primarily around romantic and/or sexual encounters between characters. ↩

- The writer’s pen-name is Takahiro’ only, with no last name. ↩

- Daikoku-bashira’ (大国柱) is ”an architectural term and means a central pillar, which has become a metaphor for a person (in many cases, a man) who is the centre of… and supports the family” (Hidaka 2010, 78). ↩

- Esu (エス; S’) is used in Japanese to refer to sadism, as in S&M’. With desu’ meaning the verb to be’, the name Esudesu’ can be read in Japanese to mean I’m an S’ (i.e., I’m a sadist’). This play on words places sexuality at the forefront of her character profile. ↩

- Many concepts from Japanese religion (Buddhism and Shinto) are used to create Noragami’s world. The terms higan’ and shigan’ are used in Buddhism to refer the world of the living and the spirit realm. ↩

- The terms shukujo’ (淑女; lady) and mukogimi’ (婿君; husband) are no longer in common use, and the negative auxiliary –nu’ (used in hajinu’ (恥じぬ)) is also archaic (Makino and Tsutsui 1995). ↩