Governor Takeshi Onaga and the US Bases in Okinawa: The Role of Okinawan Identity in Local Politics

Published July 02, 2018

Pages 29-51

https://doi.org/10.21159/nvjs.10.02

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney and Monica Flint, 2018

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

New Voices

in Japanese Studies

Volume 10

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2018

Abstract

With the increasing importance of the US-Japan Security Alliance amidst heightening regional tensions between Japan and its neighbours, the debate concerning the US base presence in Okinawa has polarised many and garnered significant attention in scholarship and the media. Using a qualitative approach, this article analyses the political rhetoric of Takeshi Onaga, who assumed office as Governor of Okinawa in December 2014. The article finds that Onaga uses an essentialist notion of Okinawan cultural identity and history as a tool for political gain to further an anti-base agenda. It contributes a new perspective to the literature on US bases in Okinawa by shedding light on the convergence of representations of contemporary Okinawan identity, ethnicity and history in the local Okinawan political debate. Further, in drawing on examples from Onaga’s Twitter and YouTube accounts, the article responds to the scarcity of literature on the relationship between social media and politics in Japan.

INTRODUCTION

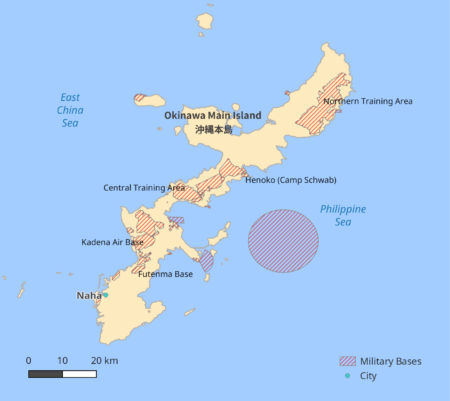

Okinawa Prefecture, a small island chain southwest of Kyushu in Japan, is renowned for its distinct history, culture and geography.1 Formerly an independent state known as the Ryukyu Kingdom, Okinawa’s history and its relationship with mainland Japan over the past 500 years has been tumultuous. Defining events include the Satsuma Invasion in 1609, annexation to mainland Japan in 1879, the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 and the establishment of a permanent US military presence from 1945.2 Against this background, and with growing contention around the US base presence in recent decades, the construction of a master historical narrative and notion of a collective Okinawan’ identity vis-à -vis the mainland has become increasingly salient in local politics. With an estimated population of 1.4 million (Okinawa Prefectural Government 2018), Okinawa currently hosts 47,300 Americans—including military personnel, affiliates and their families—on 32 bases (see map, Figure 2). The land area of these bases accounts for 73.7% of all US base land area in Japan (Okinawa Prefectural Government 2016). The base controversy centres around Okinawa’s disproportionate responsibility (imposed by the central Japanese government) for hosting US military bases. The bases have been associated with increased air and noise pollution, crime and a lack of prefectural autonomy, which intersect with a number of other significant issues such as economic development, regional security concerns, environmentalism and pacifism (Cooley and Marten 2006; Chanlett-Avery and Rinehart 2014; Hook et al. 2015). The base issue has ignited debate among scholars and activists regarding Okinawa’s alleged position as an internal colony’ of Japan that has suffered from continued exploitation and oppression since its annexation (Arakawa 2013; Arasaki 2001; McCormack 2007; McCormack and Norimatsu 2012). The most notable similarity amongst anti-base politicians, activists and scholars—despite their vastly different motivations, interests and goals—is the attempt to define what it means to be Okinawan and to use this constructed identity as a persuasive and at times emotive argument against the US military presence.

This article will examine how notions of contemporary Okinawan identity have become integral to anti-base discourse, and explore the implications of this in local politics. In doing so, the analysis will challenge assumptions of Okinawan identity as unitary or fixed; it will shed light on the pliable nature of collective identity and the internal diversity and fissures present within Okinawa. Specifically, the article focuses on the use of Okinawan identity in the political rhetoric of Governor Takeshi Onaga [翁長 雄志; b. 1950] during his election campaign of October—November 2014 and his time in office from December 2014 to the present. Okinawa’s 2014 gubernatorial election centred upon the contentious plan to relocate the Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) in Futenma (the Futenma base’), currently within the densely populated city of Ginowan, to the small coastal town of Henoko.3 Onaga campaigned as an independent conservative candidate on a fervent anti-base platform, committed to blocking base construction at Henoko. He was previously a member of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and served as Mayor of Naha, Okinawa’s capital city, from 2000 to 2014. In the 2014 election, Onaga achieved a clear victory over his three rival candidates, winning 51.6% of votes.4 As governor, Onaga has used various political and legal means to block the construction of the Henoko base.

This article analyses Onaga’s public speeches, press conferences and social media posts to shed light on the central role of a constructed authentic’ Okinawan identity in his anti-base rhetoric. By drawing upon existing insights into the fluid and political nature of identity in the specific sociocultural and historical context of Okinawa, the article will reject reductionist views that characterise Onaga’s election victory as a manifestation of unanimous anti- base sentiment amongst a unified Okinawan people. The analysis builds upon a rich body of literature that explores history as a powerful resource in identity and community formation to show how representations of group identity and historical legacies in Okinawa have been used by Onaga to secure the anti- base vote (Anderson 2006; Reicher and Hopkins 2001; Liu and Hilton 2005).

Okinawan History and Identity

Okinawa’s history has largely been shaped by the competing political and strategic agendas of significant stakeholders in the region. As a result, the constant flux in Okinawa’s geopolitical relationships has informed the complex and multifaceted nature of Okinawan identity today. Close trading ties with neighbouring countries, including the tributary relationship with China established in the fourteenth century, have imbued Okinawan traditions, architecture and cuisine with hybrid elements from diverse cultures. In the more recent past, the foreign policy objectives of Japan and the US have been the driving forces behind the key turning points in contemporary Okinawan history, beginning with the chain of events that led to Japan’s annexation of Okinawa in 1879 in the context of Japan’s expansionist agenda. Since Japan’s defeat in World War II, the US’s approach to Okinawa has been informed by the foreign policy objective of consolidating a US-centred regional order and cultivating strong allies in the Western bloc. The US-Japan Security Treaty, concluded during the US occupation of Japan, legitimated the stationing of US military bases in Okinawa, and remains of particular relevance today as geopolitical tensions in the region (such as North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile testing) increase.5

In addition to cultural legacies from the former Ryukyu Kingdom, Okinawa’s interactions with key actors in the twentieth century have had complex implications for its historical narrative and shared notions of Okinawan identity. A common narrative of Okinawan history describes its demise from former glory as a flourishing trading hub during the era of the Ryukyu Kingdom, its subjection to Japanese colonialism after the Satsuma Invasion and its eventual annexation to Japan (Siddle 1998, 117). However, a coherent idea of what being Ryukyuan’ means and how it may differ to being Japanese’ did not develop until long after the Ryukyu Kingdom had been deposed (Siddle 1998, 119), and has changed over time ever since. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, Shō Hashi [尚 巴志; 1372—1439] unified Okinawa Main Island, which had previously been divided into three separate kingdoms (Takara 1980, 43). The monarchical regime exerted influence across the entire Ryukyu archipelago, establishing the Ryukyu Kingdom. During this era, Ryukyuan vernaculars across the archipelago were diverse and often mutually unintelligible due to geographical diffusion (Heinrich et al. 2015, 1).6 It is therefore unconvincing that there existed a strong consciousness of a united Ryukyuan identity at that time, despite its frequent idealisation in contemporary political rhetoric, as will be discussed later in this article. Okinawan cultural identity is a fluid construction that is not founded in inherent truths; its contemporary characterisations must therefore be examined within the context of Okinawans’ ongoing political struggle since the process of the Ryukyu Kingdom’s annexation into Japan.

Shortly after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Meiji government moved towards fully incorporating the Ryukyu Kingdom into Japan. In 1874, it sent an expedition to Taiwan as a punitive measure after shipwrecked Ryukyuans were massacred by Taiwanese aboriginal groups in southern Taiwan. This act demonstrates an affirmation of Japanese sovereignty over the islands (Mizuno 2009, 683). In 1875, the government prohibited the tributary relationship between Ryukyu and Qing-dynasty China, and in 1879, the Ryukyu Islands were formally annexed and became Okinawa Prefecture. The Meiji government promoted language standardisation and new education reforms that emphasised Japanese nationalism, amongst other assimilation measures (Tanji 2006, 26). Initially, the Ryukyu ruling elite resisted the incorporation into Japan and maintained pro-China sentiment until Japan’s 1895 victory in the Sino-Japanese war (Siddle 1998, 120—21). Subsequently, in addition to pressure from the central government to assume a Japanese’ identity, there emerged a will from Okinawans—particularly the elite—to assimilate and be associated with the powerful, modernised nation-state of Japan for their own economic advantage (Tanji 2006, 27). Some scholars have interpreted this active will to assimilate as the internalisation of colonialism, whereby the Okinawan public wanted to be treated as equals in Japanese society, necessitating the denial of their own customs and language which were perceived by some as inferior and backwards (Clarke 2015, 622—23).

The next major turning point in the history of Okinawan identity politics came in the aftermath of the Battle of Okinawa. The US had strategised to retain the islands in the Ryukyu archipelago as separate from Japan for military use.7 In order to provide a rationale for this separation and to lessen objections from Japan, US officials classified the inhabitants of the archipelago as Ryukyuans’ (rather than Okinawans’), and therefore as non-Japanese (Siddle 2003, 134). In a process described as ”De-Japanization” and ”Ryūkyūanization”, the US military authorities aimed to construct an independent Ryukyuan identity by emphasising its cultural and ethnic uniqueness and repatriating Okinawans in mainland Japan back to Okinawa (Augustine 2015, 217—18). However, the ”Ryūkyūanization” policy ultimately backfired when its tacit implications of decolonisation and liberation were not realised under direct US military rule, fuelling a movement (known as the reversion movement’) which called for the US military to withdraw from Okinawa, and for Okinawa’s return to Japan (Augustine 2015, 222).8 Furthermore, as this article will demonstrate, this idealisation of a unique Ryukyuan identity that was promoted by US officials in the post-war era is now being used against the US in contemporary Okinawan politics.

The reversion movement gained traction in the late 1950s and 1960s, following the end of the US occupation of mainland Japan in 1952. Many Okinawan proponents of the reversion movement promoted their identities as being Japanese rather than Ryukyuan, underlining the need for ”ethnic unity” to the ”ancestral land” of Japan (Siddle 2003, 136). However, the desire to return to mainland Japan did not necessarily indicate a denial or rejection of an Okinawan identity altogether. Rather, it should be understood within the context of frustration at the increasing gap between Okinawa and the mainland, as Japan was enjoying high economic growth and democratic freedoms at the time (Siddle 2003, 136). Okinawa was returned to Japan in 1972 under the Okinawan Reversion Agreement, and the way in which Okinawans define their relationship with the mainland remains integral to how they conceptualise their collective identity today.9

More recent characterisations of Okinawan identity describe a unified people who are fighting back against centuries of suffering, oppression and exploitation (Nakano and Arasaki 1976; Arakawa 2013; McCormack and Norimatsu 2012). Tanji (2006) argues that it is the ”myth” of Okinawan ”struggle” that unites the otherwise diverse and fractured ”community of protest” within Okinawa (8). The ”myth” is defined as a story or narrative that resonates widely by drawing upon a ”large reservoir of memory” to legitimise a sense of collective identity and collective action (Tanji 2006, 7—8). The pliability and accessibility of such a myth, which draws upon key historical events including the Battle of Okinawa, US military rule and the infamous 1995 gang-rape of an Okinawan girl, allows for diverse groups to identify with this collective identity, creating a façade of unity and homogeneity (Tanji 2006).10 This research will build upon this conceptualisation of the identity ”myth” through the case study of Takeshi Onaga by examining how contemporary notions of Okinawan identity are constructed and how this plays out in local politics.

Gubernatorial Election Campaign 2014

This section will look more closely at Onaga’s campaign rhetoric to explain how and why his election campaign was successful. Takeshi Onaga campaigned as an independent anti-base candidate, despite having been a core member of the LDP and campaign manager for the LDP-backed incumbent Hirokazu Nakaima in the previous gubernatorial election [2010]. Onaga’s election campaign centred on his policies to significantly reduce the number of US bases on Okinawa Main Island and his commitment to suspend the Henoko base construction. He won the election with 100,000 more votes than the incumbent governor Nakaima (Ryūkyū Shimpō 2014). The 14.7% swing against Nakaima (Okinawa Election Administration Committee 2015, 27) can be seen as indicative of strong voter backlash against his approval of the landfill project at Henoko—against his 2010 election pledge—so that base construction could commence. Many media reports and scholars, including prominent Okinawan Studies scholar Gavan McCormack, seemed to position the election win as a demonstration of the overwhelming anti-base sentiment in Okinawa:

A week in Okinawa during November 2014…left this author with an overwhelming impression of…the determined, non-violent, democratic resistance of the Okinawan people […]. The contradiction was never so manifest as in the outcome of the 16 November election, in which the Okinawan people delivered a massive majority to the anti-base construction candidate for Governor, Onaga Takeshi, thereby declaring in effect that Okinawa would not allow construction to go ahead on the new base for the US Marine Corps on Oura Bay.

(McCormack 2014)

However, as the following analysis will show, rather than solely reflecting the electorate’s antipathy towards US military presence, the election presented insights into the power of nuanced campaign messaging, crafted to leverage the aspects of Okinawan identity with the broadest potential resonance across Okinawa’s diverse population.

Arguably, one element behind the success of Onaga’s campaign was his use of Twitter, which was ground-breaking at the time in the context of Japanese politics.11 In 2016, Twitter reported that there were over 40 million active Twitter users in Japan (Twitter Japan 2016), making it Japan’s most popular social media platform. In spite of this, the use of online platforms for political communication has lagged considerably behind its prolific use in other nations. This is likely to be a result of strict election regulations. Enacted in 1950, the Public Offices Election Law (公職選挙法) regulates electoral campaigning by controlling spending and media access with the aim to eliminate unfair advantages between candidates. It was not until April 2013 that the Japanese Diet passed revisions to the law to specifically allow candidates to use the internet as a campaign tool (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication 2013). The revisions came amidst growing global trends to leverage the accessibility and interactivity of digital platforms for political use (for example, digital platforms allegedly played a central role in Barack Obama’s successful presidential campaigns in 2008 and 2012). Japanese lawmakers anticipated that the revisions would invigorate political discussion amongst citizens, and ultimately increase political participation and voter turnout (Mie 2013).12

In this context, Onaga’s use of social media in his 2014 campaign was innovative, and in drawing on examples from Onaga’s Twitter and YouTube accounts, this article responds to the scarcity of literature on the relationship between social media and politics in Japan. Onaga’s rhetoric leverages Okinawans’ pre-existing affinities and sense of belonging to a wider Okinawan community to build collective agreement in alignment with his political objectives. Throughout his campaign, Onaga consistently framed the election not as a choice between different policies and politicians, but as an opportunity to send a powerful message to the central Japanese government: that one’s identity as an Okinawan trumps any other political allegiance. Onaga’s use of slogans such as ”All Okinawa” (オール沖縄), ”Identity over ideology” (イデオロギーよりアイデンティティー) and ”Okinawans together as one” (ç県民の心を一つに) operated throughout his campaign to appeal to prefectural citizens’ sense of ethnic attachment. For example, in one YouTube video, Onaga states:

I will resolve Okinawa’s base problem by rallying the power of the All Okinawa’ identity over ideology. I will bring together the heart of Okinawans as one and overcome the political left/right binary.[13「私は保守革新を乗り越えて、県民の心をひとつにして、イデオロギーよりはアイデンティティー、「オール沖縄」というパワーを結集して、この沖縄の基地問題を解決していきたいと思っております。」]

(Onaga 2014b)

On both a semantic and symbolic level, the slogans reinforce a sense of oneness and the importance of Okinawans coming together to successfully challenge the central Japanese government. Further, they also function powerfully in the digital media landscape: as Noakes and Johnston have demonstrated, slogans and symbols are effective mechanisms to ”crystallize the essential components of a frame in an easily recalled clip”, to ensure that a message can be spread quickly and efficiently (2005, 8). Onaga’s emphasis on collective action and unity in this example is characteristic of his entire campaign strategy, deploying Okinawa’s cultural identity as the unifying principle that transcends all other allegiances.

Onaga’s campaign also demonstrates an attention to detail around language choice that aligns with the central trope of Okinawan unity. Onaga judiciously chooses the word kenmin’ (県民; lit., people of the prefecture’) as an inclusive definition of who is Okinawan, as seen in ”Okinawans together as one” (県民の心を一つに). In the Okinawan context, kenmin’ is a ”term of self-demarcation” that closely embodies a sense of Okinawan nationalism, whilst still acknowledging a sense of belonging to mainland Japan (Tanji and Broudy 2017, 179). The use of kenmin’ connotes a sense of a cohesive community amongst the diverse island groups across the prefecture. It is significant that Onaga uses the term kenmin’ and not uchinÄnchu’ (also meaning Okinawans’), which is a term commonly used by Okinawans to distinguish themselves from mainland Japanese and convey a sense of pride in Okinawan culture, ethnicity and historical legacies (Siddle 2003, 133). The word uchinānchu’ derives from Uchinā, the name for Okinawa Main Island in local dialect; thus, uchinānchu’ only refers to inhabitants of the main island. In choosing the word kenmin’ over uchinānchu’, Onaga includes all island groups into the scope of his overarching ”All Okinawa” identity.

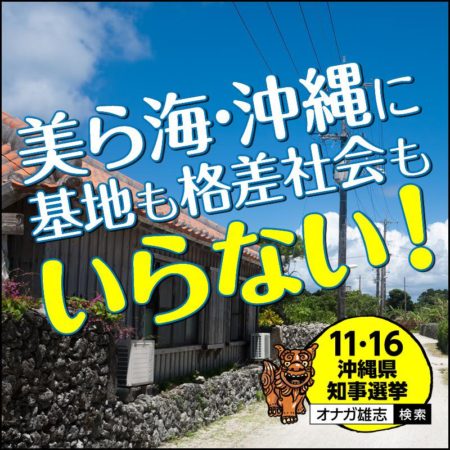

Eye-catching visuals in conjunction with slogans, as exemplified in Figures 3 and 4 from Onaga’s Twitter page, help to further amplify Onaga’s message of an inclusive community of us Okinawans’, whose collective voices have the power to sway the central government. The animal resembling a lion in both images is a depiction of a shiisā, an imaginary beast from Ryukyuan mythology that is said to ward off evil spirits. It is a significant indigenous totem that symbolises the convergence of tradition, group identity and cultural continuity (Hunter 2012, 83). Statues of shiisā are commonly seen today at the entrances and gates of homes and buildings across Okinawa. As the shiisā originated from China before being adopted by the former Ryukyu Kingdom in the 13th to 14th century (Okinawa Prefectural Government 2015), the totem has become a salient symbol of Okinawa’s hybrid culture that is distinct from mainland Japan. A small shiisā statue is the quintessential Okinawan souvenir for mainland Japanese tourists as it is seen to symbolise Okinawan culture (Hunter 2012, 83). The shiisā’s enduring presence and ubiquitous nature in everyday life show how contemporary Okinawan identity remains deeply rooted in its ancient Ryukyuan past. By tapping into cultural symbols, Onaga appeals to Okinawans’ sense of pride in their rich history and its legacies, thereby reinforcing his message of ”identity over ideology”.

Onaga in Office

Since taking office in December 2014, Onaga has actively sought media opportunities to mobilise support within Okinawa and bring his anti-base agenda before the central Japanese government. Onaga draws upon history as a symbolic resource to redefine what it means to be Okinawan and connects this with his political objectives to gain followers. In office, as with his campaign, Onaga continues to emphasise collective identity, successfully attracting public support by tapping into two emotionally sensitive aspects of Okinawan consciousness: (1) a shared ancestry and history, and (2) the collective memory of war and hardship.

Shared Ancestry and History

The previous section illustrated how Onaga successfully framed the election as a choice of local identity over political ideology, a message which he has continued to foreground throughout his time in office to date. Since assuming office, Onaga has often drawn upon allusions to shared ancestry and the legacy of the ancient Ryukyu Kingdom. For example, in his 2014 inauguration address, Onaga outlined his policy visions, emphasising the importance of recognising and drawing inspiration from Okinawa’s ancient history in order to build a prosperous future:

As outlined in the Okinawa 21st Century Vision plan, which was created with the collective wisdom of Okinawan residents, I will leverage the soft power inherited by our uyafāfuji [ancestors], and…open up Okinawa to create a place where umanchu [all Okinawans] can smile.[14「県民の英知を結集して作られた沖縄21世紀ビジョンで示された将来像の実現を目指して、うやふぁーふじから受け継いだソフトパワーを活かし……、沖縄を拓き、うまんちゅの笑顔が輝く沖縄を創りあげてまいります。」 ]

(Onaga 2014a)

The strategic use of Okinawan vocabulary (uyafāfuji’, discussed below, and umanchu’, meaning everyone’ or all [Okinawans]’) in preference to standard Japanese encourages a sense of familiarity and togetherness by highlighting a shared origin with other Okinawans and denies access to those outside of the Okinawan cultural sphere. In particular, the culturally significant Okinawan word uyafāfuji’, meaning ancestors’, alludes to the central tradition of ancestor veneration in the indigenous Ryukyu religion (琉球神道) and increases the speech’s resonance by reaching into the depths of the Okinawan cultural consciousness.

In the contemporary context, Onaga’s use of local vocabulary in highly publicised official speeches may also be seen as an act of resistance and revival in response to historical efforts to impose standard Japanese upon the prefecture. The Meiji government’s measures to standardise language in Okinawa were implemented in the early 20th century, following Okinawa’s annexation. These measures included penalising children at school for speaking in local dialects, with punishments including reduction of grades or being made to wear a wooden ”dialect tag” (方言札) around their necks (Anderson 2009, 31—34). In addition to employing Okinawan lexicon, at times Onaga also speaks entire paragraphs in Shuri dialect.13 For example, in a speech at a prefectural citizens’ assembly, he begins his address thus:

Hello everyone. My name is Onaga Takeshi, the Governor of Okinawa Prefecture. I am pleased to be here today. Thank you everyone for gathering here to stop the new Henoko base…I think there are over 30,000, maybe 40— 50,000 Okinawans here. Thank you to so many that have gathered here today despite the heat. Let’s do our best.[16「はいさい。ぐすーよーちゅううがなびら。うちなー県知事ぬ、うながぬたけしやいびーん、ゆたさるぐとぅうにげーさびら。新辺野古基地を造らせないということで、ご結集いただいた皆さん……。3万人を超え、4万、5万と多くの県民が集まっていると思っている。うんぐとぅあちさるなーか、うさきーなー、あちまてぃくぃみそーち、いっぺー、にふぇーでーびる。まじゅんさーに、ちばらなやーさい。」]

(Onaga 2015e; underline added to indicate use of Okinawan vocabulary)

By deploying the notion of common ancestry and kinship for political means, Onaga appears to insinuate that being a genuine’ Okinawan inherently necessitates an anti-base point of view.

The important role of kinship in constructing an oppositional consciousness against the Henoko base has been identified in previous studies. Inoue’s (2007) anthropological research represents the most comprehensive study into the relationship between identity construction and attitudes towards US bases. Specifically, Inoue elucidates the internal diversity and emerging societal fissures in the town of Henoko, revealing an explicit demarcation between ”genuine” Henoko residents and the so-called ”out-of-towners” (2007, 142). According to the study, ”genuine” Henoko residents were those with extended familial lineage from the area, sometimes tracing back to the Ryukyu Kingdom, whilst ”out-of-towners” were residents who immigrated to Henoko later, particularly after the war. It was perceived that the new ”out-of-towner” Henoko residents ”wanted the offshore base because they did not share Okinawa’s collective memories of war, the bases, and the servicemen, while genuine natives did share those memories and, consequently, did not and should not want the new base” (Inoue 2007, 142—43). Inoue (2007) concludes that this ”genuine, righteous” anti-base identity of the native Henoko residents was being constructed as the authentic Okinawan perspective that was combatting the ”immoral” and ”corrupt” power of Tokyo and Washington (143). I argue that Onaga similarly uses the notion of ethnicity and the historical differences between Okinawa and mainland Japan to frame the US base dispute as a conflict between the inherently peaceful island of Okinawa and an overbearing central government.

Furthermore, Onaga often juxtaposes positive images of the historical Ryukyu Kingdom as a peaceful trading hub with the tragic events that have occurred since its annexation to Japan, thereby implying that the Japanese government’s policies have led to Okinawa’s economic stagnation.14 Okinawa remains Japan’s poorest prefecture, as it did not share the post-war high economic growth period with the mainland and it relies on economic stimulus measures from Tokyo (Cooley and Marten 2006). In one press conference, Onaga begins his speech by describing the former Ryukyu Kingdom’s flourishing culture and economy, asserting that the Ryukyuans were the centre of naval trade between China, Japan and Southeast Asia for many centuries, until the islands became part of the greater Japanese territory and their prosperity was systematically taken away (Onaga 2015d). He similarly echoes this message in another speech, following the lawsuit filed by the central government against Okinawa Prefecture regarding Onaga’s cancellation of landfill permission at Henoko:

For a period of about 500 years, Okinawa was the Ryukyu Kingdom. We enjoyed a great period of trade that encompassed Japan, China, Korea and Southeast Asia. Ryukyu was annexed to Japan in 1879, 136 years ago. Ryukyu strongly resisted [the annexation], so the Japanese government employed armed forces under the label Ryūkyū shobun’ [処分; disposal’]. What awaited after the annexation was World War II, 70 years ago. Japan’s only ghastly ground warfare took place [in Okinawa], incurring both military and civilian casualties. Two hundred thousand people, including approximately 100,000 Okinawan civilians, were sacrificed.[18「簡単に沖縄の歴史をお話しますと、沖縄は約500年に及ぶ琉球王国の時代がありました。日本と中国・朝鮮・東南アジアを駆け巡って大交易時代を謳歌(おうか)しました。琉球は1879年、今から136年前に日本に併合されました。これは琉球が強く抵抗したため、日本政府は琉球処分という名目で軍隊を伴って行ったのです。併合後に待ち受けていたのが70年前の第二次世界大戦、国内唯一の軍隊と民間人が混在しての凄惨(せいさん)な地上戦が行われました。沖縄県民約10万人を含む約20万の人々が犠牲になりました。」

The lawsuit was filed in November 2015. See footnote 3 and the timeline in the Appendix for further details.]

(Onaga 2015c)

The phrase Ryūkyū shobun’ (琉球処分) is often translated as the disposal of Ryukyu’, and originally referred to the process of Japan establishing Okinawa Prefecture in 1879 by formally annexing the Ryukyu domain. However, many Okinawans refer to a number of events in Okinawan history as acts of shobun, including the Satsuma invasion, the US occupation and the 1972 reversion to Japan, thus connecting a series of tragic and oppressive events enforced by the powers of Japan and the US (McCormack 2007, 155).

Moreover, in the conclusion of his speech, Onaga again stresses the true’ cultural essence of Okinawa as being the legacy of the once-thriving Ryukyu Kingdom. He asserts:

The future of Okinawa should exhibit the spirit of bankoku shinryō and become the bridge between Japan and Asia, and someday become a neutral zone of peace for the Asia-Pacific region. That is my wish.[19「沖縄の将来あるべき姿は、万国津梁の精神を発揮し、日本とアジアの架け橋となること、ゆくゆくはアジア・太平洋地域の平和の緩衝地帯となること。そのことこそ、私の願いであります。」]

(Onaga 2015c)

Bankoku shinryō (万国津梁; bridge between nations’), is an Okinawan expression alluding to a famous bronze bell that was cast in 1458 and hung in the main hall of Shuri Castle in Naha. The bell is known as the Bridge of Nations Bell due to its inscription describing Ryukyu Kingdom’s prominence in maritime trade between East and Southeast Asia (Ota 1996, 40), and it has come to symbolise the former prosperity of Ryukyu as a dynamic and hybrid trading hub. In a sense, the governor’s frequent allusions to Okinawa’s past as inspiration can be perceived as reclaiming the notion of being uncivilised’—a notion embedded in the Meiji Government’s assimilation policies towards Okinawa soon after its annexation—and redefining it as meaning ”not yet corrupted by power and militarisation” (Siddle 1998, 127).

Collective Memory of War and Hardship

Both during his electoral campaign and later as Governor, Onaga has also effectively used evocative imagery of and allusions to the experiences of war and suffering to capitalise on the powerful memories of the Battle of Okinawa that are embedded into the social fabric of the Okinawan community. For example, in one speech, Onaga emphasises the historic vulnerability of Okinawan citizens to US military forces by evoking images of weaponry and powerful machinery:

After the war, Futenma Air Station and other bases were seized while Okinawan citizens were being housed in refugee camps. Then, residential land was forcibly taken with bayonets and bulldozers, and bases were constructed.[20「普天間飛行場もそれ以外の基地も戦後、県民が収容所に収容されている間に接収をされ、また、居住場所をはじめ、銃剣とブルドーザーで強制接収をされ、基地建設がなされた。」]

(Onaga 2015e)

The image of the peaceful everyday life of innocent citizens juxtaposed with the forceful seizure of Okinawan land and usurpation by the US military portrays Okinawans’ sense of displacement and loss in the face of an overwhelming and domineering power. In another example, Onaga criticises the government for exploiting Okinawa purely ”as a territory” (Onaga 2015f), and contrasts mainland Japan’s economic success with Okinawa’s struggles:

For 27 years, from the time under US military administration to the reversion, we Okinawans were not Japanese citizens, nor American citizens. Yet, Okinawan bases were used for wars like Vietnam […]. I think that, while Japan had peace and high economic growth after the war, Okinawa, for 27 years, was made to be used freely by the US military.[21「沖縄は、27年間、米軍の施政権下から外された時には、日本国民でもない、アメリカ国民でもないなかで、ベトナム戦争を、沖縄の基地を使って戦争をしたわけなんです……日本の戦後の平和と高度経済成長は、沖縄が27年間、米軍が自由に使うことによって、私は成り立ったもんだというふうに思っております。」 ]

(Onaga 2015f)

The persuasiveness of Onaga’s use of wartime and postwar imagery is reinforced by his ability to seamlessly connect historical events with today’s Henoko base dispute to position Okinawa as shouldering a prolonged burden in the form of the US military presence. For example, in a press conference on the lawsuit filed by the central Japanese government against Okinawa for revoking approval for Henoko construction, Onaga argues:

[The base construction at Henoko] appears to be just like the bayonets and bulldozers from the war. Okinawa’s lack of right to self-determination is no different from 70 years ago, except that this time it is not the US military, but the Japanese government that is using the law as its shield.[22「今回、海上での銃剣とブルドーザーの様相を呈してきていることは、やはり沖縄県民の自己決定権のなさについては、あの70年前も今回もそうは違わないなというようなことを、今度は米軍ではなく、日本政府が法律を盾に取ってやることである。」 ]

(Onaga 2015b)

Linking past and present, Onaga insinuates that the new base construction at Henoko is yet another instance of the central government subjugating the Okinawan people to its will by actively dismissing their opposition and using any means possible to ensure that the Henoko plan goes ahead. Onaga also positions the anti-base movement as a natural response by Okinawans to the collective cultural memory of wartime atrocities. For example, in an address on Okinawa Memorial Day, the governor states:

[The reason why Okinawans can never forget the grief caused by the Battle of Okinawa] is because we Okinawans remember clearly the tragedy brought on by war, with our eyes, ears and skin; from our hearts, we wish for peace for the people who were made victims of war, and we hope for eternal peace.[23「それは私たち沖縄県民が、その目や耳、肌に戦争のもたらす悲惨さを鮮明に記憶しているからであり、戦争の犠牲になられた方々の安らかであることを心から願い、恒久平和を切望しているからです。」]

(Onaga 2015a)

Furthermore, Onaga also frequently links recent crimes committed by US military service members with broader historical contexts, redeploying them as powerful symbols for the injustice and oppression historically suffered by Okinawa at the hands of the US.15 One example of this is violence against women by US military servicemen. In a speech at a prefectural gathering in June 2016, following the sexual assault and murder of a twenty-year-old Okinawan woman by a US base employee that April, Onaga connects individual crimes against women committed by US service members with the presence of the US military as a whole:

This kind of inhumane and cowardly crime that violates women’s rights is absolutely unforgivable and I feel strong indignation […]. As Governor, I have strongly requested a review of the US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement in order to protect Okinawans’ lives, assets, dignity, human rights, and for the safety and security of future children and grandchildren.[25「そしてこのような非人間的で女性の人権を蹂躙(じゅうりん)する極めて卑劣な犯罪は断じて許せるものではなく、強い憤りを感じております。沖縄県知事として県民の生命と財産、尊厳と人権、そして将来の子孫の安心と安全を守るために日米地位協定の見直しを強く要望します。」

The US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) governs how US military forces, related personnel and civilians are to be treated by Japanese authorities for any crime. The agreement has come under scrutiny many times since its inception in 1960, particularly after the 1995 rape case.]

(Onaga 2016)

Onaga draws a causal relationship between the rape and the US military base presence, positioning the individual crime as symptomatic of the asymmetrical power dynamic between Okinawa and the US military.

As the above examples illustrate, Onaga has leveraged the strong collective memory of wartime atrocities, linking these historical instances of injustice to the current base dispute to bolster his anti-base position. The findings from this analysis align with those of Inoue’s (2007) study on the activist work by a grassroots anti-base organisation centred in Henoko. Inoue’s study found that the Henoko residents’ ”oppositional collective consciousness” and strongly negative attitude toward the US military was grounded in their collective memory of historical issues of subjugation, war and adversity (Inoue 2007, 144). By evoking these memories, Onaga appeals to the deep sense of loyalty and solidarity of a people who have been subjected to the violence of ground warfare and prolonged hardship.

Conclusion

The US base controversy in Okinawa has been a polarising and highly contentious issue in local Okinawan politics in recent years. Central to the base debate is the perception of Okinawa’s position in relation to mainland Japan, and the interplay of shared notions of collective identity with politics. Takeshi Onaga led a successful campaign in the 2014 Okinawan gubernatorial election as an independent anti-base candidate. Whilst many anti-base activists touted the election as a clear reflection of unanimous, prefecture- wide anti-base sentiment, I have argued that the reality is more complex. Fissures and frictions between different interest groups still exist. The US base presence and the Futenma relocation dispute—the most important issue of the 2014 election—directly involves environmentalists, landowners, pacifists and individuals spanning the political spectrum. Onaga successfully leveraged the notion of a collective Okinawan identity to bridge ideological divides between these diverse groups and mobilise political support. The fact that one’s affiliation with a particular political party or ideology can be eclipsed by an attachment to the imagined community of Okinawa shows the power of historical representation and identity in local politics.

It is precisely because the base issue intersects with so many different interests that an ”All Okinawa” unity is possible. Okinawan identity has been continually defined, redefined and expanded throughout history. It is often inextricably linked to a political function and always encompasses Okinawa’s self-perception of its position vis-à -vis mainland Japan. Agreements between the US and the central Japanese government legitimise the US military presence in the island prefecture (in spite of local protests), and the Futenma dispute has driven the question of Okinawa’s place within Japan to the forefront. In essence, this article aimed to answer the question: what does it now mean to be Okinawan and how does this play out in local politics?

Okinawa belongs to Japan but is simultaneously separate from it. The seemingly paradoxical and dual nature of Okinawan identity affords local politicians like Onaga great potential for leveraging local identity and related sentiment when politically advantageous. In the context of the US base controversy, Onaga uses a romanticised version of a pacifist Ryukyuan legacy and stories of suffering from war and colonialism to emphasise Okinawa’s different—and tragic—history compared with mainland Japan. The three main threads that underpin the prevalent version of Okinawan history include: (1) prosperity and peace during the Ryukyu Kingdom days, (2) oppression, destruction and tragedy at the hands of Japanese colonialism, and finally (3) a united front of resistance and struggle against inequality and continued suffering. This account of history under-represents the relationship between Tokyo and Okinawa and the will of the people to join (or return to) the Japanese state at different times throughout history. As a result, the story of Okinawa’s relationship with Japan is one of one-sided, continual oppression and victimhood. Not only does this narrative present as a persuasive argument to Tokyo for freedom from a disproportionate US base presence, but it also emotively ties diverse groups of people within the prefecture together under one collective identity. In reality, it is the anti-colonial struggle that has given rise to the present form of Okinawan collective identity. Seen in this light, the power of the narrative deployed by Onaga lies in its seamless construction: it does not appear carefully crafted, but seems to have been inherited from Ryukyuan ancestors.

This article has illustrated how Onaga taps into this shared sense of attachment and community to promote engagement and support for his political agenda. Onaga effectively draws upon a rich stock of stories, cultural symbols and memories to bind diverse individuals and communities into one ”All Okinawa” identity. In doing so, Onaga also builds up his own symbolic and cultural capital to gain greater electoral support. My analysis of the 2014 gubernatorial election reveals the immense unifying power of collective identity which can override clashing political ideologies. This article has also shown how a deep understanding of Okinawan social consciousness can provide an abundance of symbolic resources and persuasive power in the local electorate. Given the success of Onaga’s unifying strategy, backed by the innovative use of social media (particularly Twitter), it will be interesting to observe how Onaga and other candidates approach the upcoming gubernatorial election towards the end of 2018.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- At present, Okinawa Prefecture is comprised of the central Okinawa Islands and southern Sakishima Islands, whilst the neighbouring Amami Islands belong to Kagoshima Prefecture (see map, Figure 1). All three island groups belonged to the indigenous Ryukyu Kingdom until 1609, when Amami was ceded to the Satsuma clan after the Satsuma Invasion. Throughout this article, Okinawa’ is used to refer to Okinawa Prefecture. ↩

- The Shimazu clan from the domain of Satsuma (present-day Kagoshima Prefecture) invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1609. The Kingdom’s tributary relationship with China continued while it became a vassal state under Satsuma. Meanwhile, the Amami Islands were annexed to the Satsuma domain, and today remain in Kagoshima Prefecture rather than Okinawa See Appendix for a timeline of Okinawan history. ↩

- In 1996, the Japanese and US governments agreed to close the US base in Futenma upon completion of offshore replacement facilities on the coast of Henoko (a less populated area on Okinawa Main Island), due to safety concerns for nearby Ginowan residents. However, the closure has not been executed as the central Japanese and Okinawan prefectural governments are yet to reach an agreement regarding the location of the replacement base. The preceding Okinawan governor, Hirokazu Nakaima, initially rejected plans to construct the new base at Henoko. However, in December 2013, Nakaima conceded that Tokyo’s solution was the most pragmatic and approved construction to start at Henoko. In October 2015, newly elected Governor Onaga revoked Nakaima’s approval, thereby suspending construction of the Henoko base. This led to a series of court battles, culminating in December 2016 when the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the national government and declared Onaga’s action illegal. Construction at Henoko recommenced soon after (Shimada 2016). ↩

- Onaga’s main opponent was the incumbent (and LDP-backed) governor Hirokazu Nakaima (仲井眞 弘多; b. 1939), who won 37.3% of votes (Okinawa Election Administration Committee 2015, 27). ↩

- The security pact between the US and Japan was conceived alongside the San Francisco Peace Treaty in Under the alliance, Japan’s security is guaranteed by the US in return for Japan allowing the US to station troops at various bases on Japanese territory (Calder 2004, 138-39). ↩

- It is generally accepted that there are five main Ryukyuan dialects (with many more local varieties): Amami, Okinawan, Miyako, Yaeyaman and Yonaguni (Heinrich et al. 2015, 1). The language used by the Ryukyuan Court in Shuri (located on Okinawa Main Island) was recognised as the official language in the former kingdom (Clarke 2015, 633). ”Okinawan” dialect generally refers to this particular variety of Ryukyuan language. ↩

- The Battle of Okinawa was a major battle in the Pacific War (1941—45), fought between US and Japanese forces as ground warfare on Okinawan soil from April to June 1945. In addition to the tens of thousands of deaths of Japanese and Okinawan army conscripts and US soldiers, there are estimates that up to 130,000 of the 300,000-strong civilian population died as a result of the battle (Ota 1996). ↩

- The Amami Islands were returned to Japan in December 1953; however, Okinawa Prefecture (Okinawa and Sakishima Islands) was not returned until 1972. ↩

- The Okinawa Reversion Agreement (沖縄返還協定) is an agreement between Japan and the US in which the US returned control of Okinawa Prefecture to Japan. ↩

- In 1995, a twelve-year-old Okinawan girl was abducted and raped by three US military service members. The incident took place near Camp Hansen on Okinawa Main Island, where the three US military service members were stationed. The crime was widely publicised in Okinawan and mainland Japanese media, and sparked public outrage and debate on the continued presence of US forces in Okinawa. As a result, the US and Japanese governments established the Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO) (沖縄に関する特別行動委員会) in November 1995 to examine ways to reduce the base burden on Okinawan people (Chanlett-Avery and Rinehart 2014, 7). ↩

- The 140-character limit on Twitter allows for quite substantial messages in Japanese, particularly with the use of kanji character compounds (it was for this reason that Japanese, along with Chinese and Korean, was exempt from Twitter’s 2017 character-limit increase). For further information, see: https://blog.twitter.com/official/en_us/topics/product/2017/Giving-you-more-characters-to-express-yourself.html. ↩

- While some Japanese politicians have embraced the opportunity to communicate directly with constituents, more traditional’ methods of handshaking and speechmaking in the streets seem to remain the favoured methods for most (Mie 2013). ↩

- Shuri dialect is one variety of Ryukyuan language spoken on the Okinawa Main Island. ↩

- For example, the Battle of Okinawa is widely accepted as one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific War, with a considerable number of civilian casualties (see footnote 7). The 1972 reversion of Okinawa to Japan after the US occupation has also been seen by some as a deception: while Japan regained administrative control, much of Okinawa’s land was not returned to locals, but rather allocated for the construction of US military bases (McCormack and Norimatsu 2012). Onaga also foregrounds incidents of crime, such as the 1995 rape incident, and other tragic events in contemporary Okinawan history. ↩

- Another widely recognised symbol of Okinawan sacrifice and victimhood is the Himeyuri Student Nurse Corps Unit. The unit was comprised of over 200 female students from two Okinawan high schools during the Battle of Okinawa. They were deployed as student nurses for Japanese soldiers at the frontline, and the majority perished in the last days of the battle (Angst 2001, 250). ↩