The Localisation of the Hana Yori Dango Text: Plural Modernities in East Asia

Published January, 2011

Pages 78-99

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21159/nv.04.04

New Voices

Volume 4

© The Japan Foundation, Sydney, 2011

Permalinks for references are available in the HTML version of this article.

Abstract

This article examines the circulation and reception of the original Japanese shōjo manga text, Hana Yori Dango, through the three sites of Taiwan, Korea and Japan to both identify similarities and to investigate also specific differences between versions and how these differences relate to both cultural distancing and to cultural proximity.

The distance-closeness binary is most informed by the historical relationship Japan has had under Western socio-politico-cultural subjugation that in turn has informed the colonial relationship both Taiwan and Korea have had with Japan. The remnant of these (ongoing) relationships has directed a subjective encoding onto versions of the text adapted in East Asia. Therefore, the appearance of similarity between versions is underscored by social, political and cultural differences contextualised locally and promoted globally as a polymorphous and multi-layered plurality.

Introduction

Between the late 1950s and the early 1990s, Japan was seen as a miracle country’,1 an economic powerhouse that embraced an increasingly globalised network. Japan’s path to modernisation, however, was fraught by its contradictory status as both an ex- imperial power and a culturally subordinated non-Western nation. From the Meiji era (1868-1912), through to the war-time era and even into the post-war years and the signing of the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty between the Allied Powers and Japan, the situation of Japan striving to be a rekkyō‘ (Great Nation), but always subjugated to Western influence, created tension and complexity. The Japanese economic miracle concealed the hostilities created by this history behind a totalising notion of American cultural hegemony which saw Japan embrace American cultural models that expressed an idealised model of Western modernity.

The American cultural hegemony that dominated Japan, however, was skilfully appropriated and turned to Japan’s advantage by using it as a model to establish a similarly all-encompassing Japanese cultural hegemony in East Asia. From the post- war era through to the 1990s, Japanese cultural products flowed into the East Asian region, thus establishing Japan as a model of Asian modernity. Nevertheless, from the start of the 1990s, the Japanese economy stalled, so that the asymmetrical flow of cultural materials between Japan and its Asian neighbours became more balanced. Throughout East Asia, markets deregulated in response to the forces of globalisation, which in turn resulted in rises in standards of living’ as levels of industrialisation across the region gradually matched those of Japan. While the rhizomatic flow of popular culture throughout East and Southeast Asia is evident in all media and genre, this paper will focus on the circulation between Japan, Taiwan and Korea of a television drama series that first appeared as the manga (comic) in Japan entitled Hana Yori Dango. The comic was then adapted by Taiwanese and Korean television production companies for distribution in these two regions before being adapted again for television in Japan.

Examining the circulation and reception of Hana Yori Dango through the three sites of Taiwan, Korea and Japan will permit an investigation of the existence or otherwise of a shared East Asian contemporary space informed by a multilayered imaginary of modernity which allows for a plurality of culturally specific experiences that are different but equal’.2 This article further problematises the extent to which the portrayal and decoding of modern lifestyles across national boundaries are layered and overlapped, and how different modes of Asian cultural modernity are articulated in them’.3

The analysis of the texts themselves will be conducted through a framework developed from the work of Russian formalist, Vladimir Propp. It will be argued that the representation of Hana Yori Dango follows a pattern of coded functions identified by Propp that constitutes the morphology of the fairytale’. In the context of Hana Yori Dango, the fairytale is a narrative supported by contemporary themes and images of youth constructing their identities in the modern East Asian urban environment.

The ready acceptance of Hana Yori Dango as a text and aesthetic model across East Asia – despite quite different political structures and colonial experiences over the last century in the three sites discussed – points to the story’s resonance with common concerns, dreams, and experiences. That common experience, I will argue, is the experience of Asian modernity problematised by the artefacts of post-colonialism and Confucian values’. The research direction of the paper examines the cross-cultural dynamics or popular culture flows around East Asia and is therefore not confined to one particular academic field, a perspective that follows the ‘multidisciplinary studies’ approach that characterises the work of scholars such as Koichi Iwabuchi, Leo Ching and Simon During.

Hana Yori Dango and its variants

The three versions of the TV drama Hana Yori Dango were adapted from a popular Japanese shōjo manga (girl’s comic) of the same title.4 The series was created by the Japanese cartoonist, Kamio Yoko, and serialised in the girls’ magazine, Margaret,5 between 1992 and 2003.6 Thirty seven volumes of the comic book version (tankōbon) were also published during the same period. Hana Yori Dango has been chosen as a representative example of cultural content originally produced in Japan which was then shaped and transformed to impact on other markets in the region. During the 1990s, the comic version of Hana Yori Dango was imported to Taiwan and South Korea where it was extensively translated and popularised. Comic Ritz, a Taiwanese-based company, later re-produced the comics into the phenomenally successful television drama, Liúxīng Huāyuán (Meteor Garden, hereafter referred to as MG). Since 2001, this drama has been exported to and broadcast in more than ten East Asian countries. In spite of its presence from 1895 to 1945 in Taiwan as an imperial power, post-war Japan has had a positive relationship with its former colony, Taiwan.7 It therefore comes as no surprise that the first television adaptation of Hana Yori Dango occurred in Taiwan. The four young male actors in the Taiwanese drama (hereafter referred to as T-drama) later re-grouped for the Sony Music label to form the music unit known as F4 (Flower Four), the name given to a schoolboy group in the original comic.

The success of MG in Taiwan led the Japanese television company TBS8 to make their own adaptation of the original manga in 2005, retaining the title Hana Yori Dango. This was followed in 2007 by a sequel, Hana Yori Dango Returns (together referred to hereafter as HYD). The high ratings of both productions inspired TBS in 2008 to launch Hana Yori Dango Final as a movie involving locations in Hong Kong and Las Vegas.9 The popularity of both MG and HYD led to Korea producing their own local version screened by KBS2TV10 in 2009 as Kkot Boda Namja (”Boys Over Flowers“, hereafter referred to as BOF). The Korean version was a huge success both domestically and throughout Asia with a peak local viewer rating of 35%.11

Origin and Adaptation

Like all shōjo narratives, Hana Yori Dango focuses on the choices and actions that girls make to negotiate their transitions out of the safety of adolescence into the more defined states of adulthood.12 The shōjo heroine is always, in one way or another, an active agent engaged against both the villains of her narrative and the social ills that created them. By deferring womanhood and its attendant responsibilities, the girl maintains the open-ended possibility of adolescence.13 Yukari Fujimoto points out that shōjo manga is not only a realm which reflects women’s desires and values, but also one in which the contemporary messages contained within the shōjo narrative appeals to a wider audience that includes male viewers.14

In the storyline, the protagonist, Tsukushi – named after a tough wild weed15 – is a girl from an average family. She is nonetheless full of fighting spirit and optimistic cheerfulness. Tsukushi attends a prestigious college (eitoku gakuen) ruled by the F4 (Flower Four), a group of four male students each from a powerful and wealthy family. Although Tsukushi’s family hopes she will meet a rich boy at the college and marry into wealth, Tsukushi hates everything about the college including her snobbish classmates. She especially hates herself ‘ in being unable to confront the corruption and elitist authority within the school hierarchy. She just quietly gets on with attending to her studies, hoping that time in the college will pass without any incident or problems. One day, however, when she stands up for a friend being tormented by Tsukasa Dōmyōji – the leader of F4 – Tsukushi is red-flagged’ as a rebel. As a result she is bullied by other students at the order of the members of F4. In spite of the fact that he is one of the boys demanding her mistreatment, F4 member, Rui Hanazawa, helps Tsukushi when she is attacked by a group of male students. Following this attack Tsukushi decides that she will not tolerate any more ill treatment by F4. She then physically strikes Tsukasa as a declaration of war’ on the F4 group.

Ironically, Tsukasa, who has never before been challenged by another student, begins to develop feelings for, and tries to woo, Tsukushi, who gradually begins to spend more time with F4. As the story progresses, Tsukasa falls in love with Tsukushi and she in turn learns how to open herself to his affection. As love continues to blossom, Tsukasa’s imperious businesswoman mother discovers the couple’s relationship and deems it unsuitable. She therefore does everything in her power to keep the two apart, even arranging a marriage for Tsukasa. Other complications arise as Rui falls in love with Tsukushi and, in a twist of fate, Tsukasa loses his memory after an accident. In the end, however, Tsukasa and Tsukushi learn that love (putatively) conquers all. For Tsukushi, it is a journey of regaining her self-identity, whereas for Tsukasa, it is a journey to discover his self-identity.

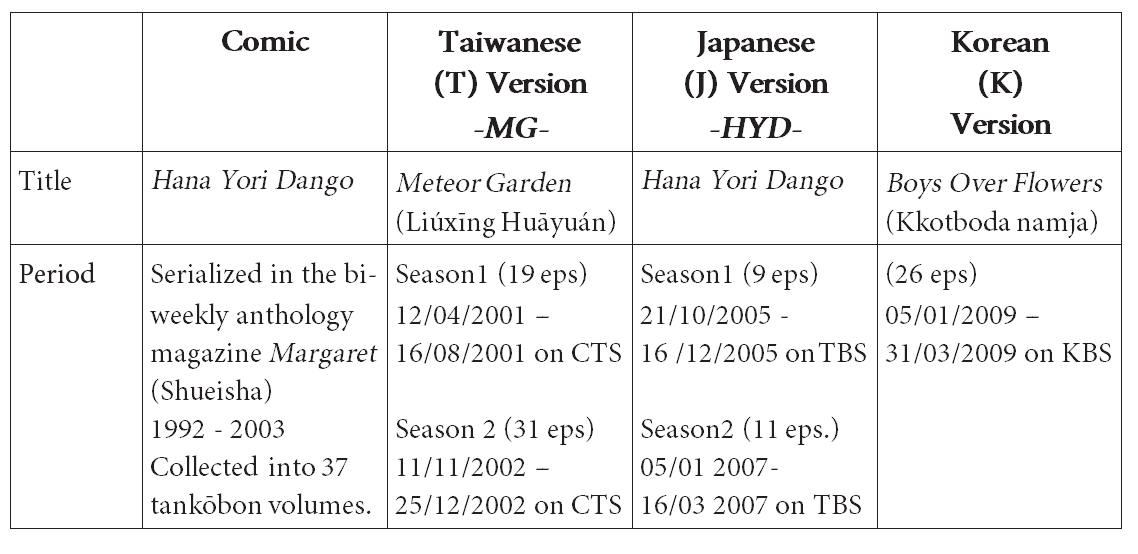

The following table introduces the characters from the comic and also gives the broadcast periods for each of the three television versions under study.

Table 1: Comparing versions

Morphology of the Folktale

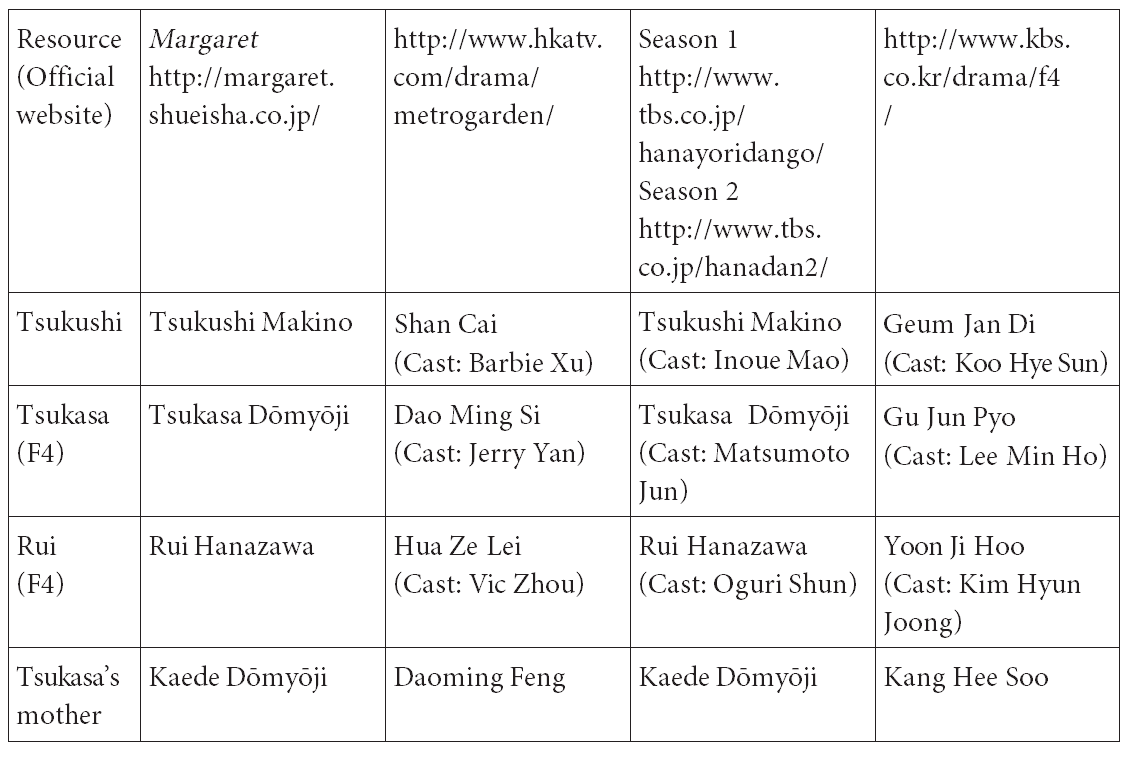

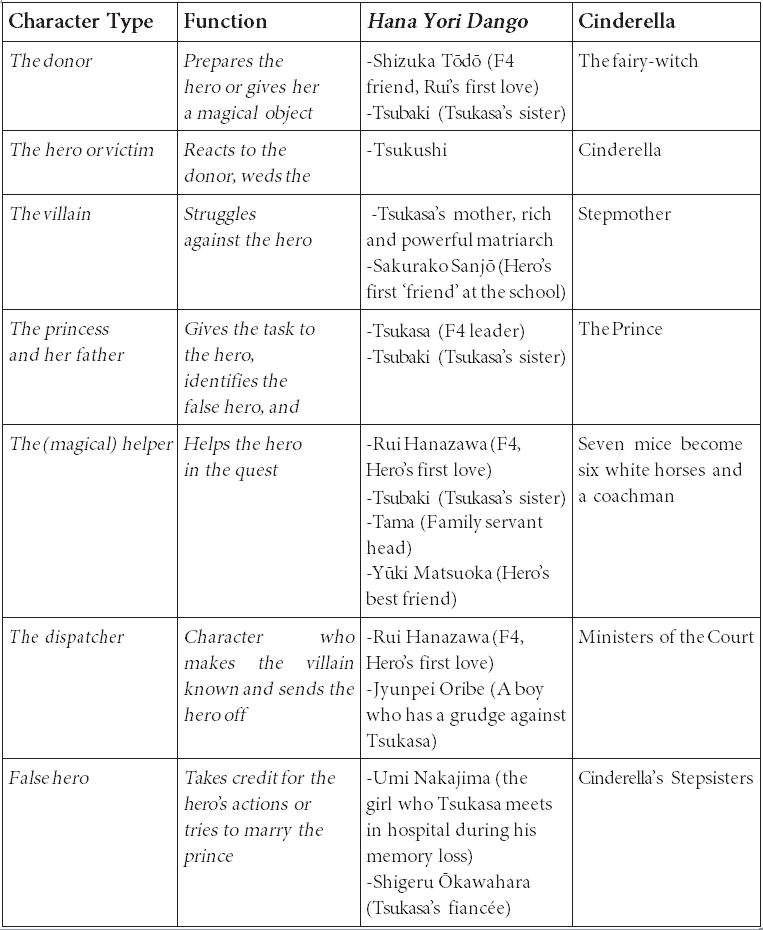

Hana Yori Dango can be regarded as a modern variant of the classic Cinderella folk tale. As such, it lends itself to analysis in terms of Propp’s morphology, outlined by Alan Dundes (1984) and John Fiske (1987), which regards the folk narrative as a systematic structure of coded functions.16 In applying this Proppian logic to Hana Yori Dango we have taken, as representative of the three versions, the Japanese comic and TV drama names and events and aligned these against the story of Cinderella. In devising a set of coded functions, Propp examined over one hundred Russian folktales. He thereby concluded that, while characters could be permitted to have more than one functional role, all folk tale characters could be resolved into only seven broad character archetypes. These seven Proppian archetypes can be identified in both Hana Yori Dango and also in Cinderella and are listed in the following table. Fiske defines character type in terms of a sphere of action’ rather than through the sphere of gender.17 It needs to be noted here that in Hana Yori Dango the gender roles of hero and princess have been reversed, so that the heroine Tsukushi becomes a Proppian hero and the prince Tsukasa becomes a Proppian princess.

Table 2: Archetypes

Propp’s formalistic approach has not been without criticism. Casey et al., for example, suggests that this type of content analysis’ is too crude a device to tell us much about the way in which media texts actually work’.18 Nevertheless, for the purpose of this study Proppian archetypes are useful for defining themes embedded in a text and for qualifying encoded contexts and characters.

Common Themes in Hana Yori Dango

Although the various productions of Hana Yori Dango have been localised to meet the preferences of their regional audiences, it is possible to identify core elements common to each version. These core elements include power struggles between the classes and gender, family unity, transformation and the affirmation of the heroine. Where the storyline is the same across versions, I have elected to use the Japanese names generically unless discussing a particular versional character. Examples taken from scenes cited in the following sections refer to all versions of the text in order to demonstrate a common thread among versions.

Power

The series is not only a love story but a drama about power and control, a theme universal to the dynamics of family, education, work and social group relations. The drama gives a microanalysis of the opposing dynamic of individual power versus the power of institutionalised expert knowledge, a dynamic that Michel Foucault refers to as the public right of sovereignty’ versus a polymorphous disciplinary mechanism’.19 The former is represented by the heroine (Proppian hero), Tsukushi, while the latter is shaped through the Dōmyōji (Tsukasa’s family) empire.

Tsukushi is initially regarded as an outsider or commoner’ and we see her common’ lifestyle when after school she returns to her real’ world where she lives in a small residence with her family and works part-time in a shop. Parallel to this, the viewer is also taken into the world of the establishment’. Here, F4 members walk and move about with an air of superiority, idolised by groups of students parting the way for F4 catwalk’ appearances. Tsukushi is not impressed; rather she finds the setting repugnant. She also struggles to reconcile her sense of self as a moral person, especially as her silence becomes tacit assent to the social abuses that occur in the school. After being the subject of severe bullying, Tsukushi finally makes clear her intention to resist domination by the hegemonic forces that control the school in her declaration of war’ against Tsukasa (Proppian princess). When Tsukasa tries to assert his power, Tsukushi knocks down the figurehead of the establishment by firing back with her own verbal assault: I don’t care if you’re the son of a plutocrat. Someone like you hasn’t even worked hard for money so don’t get too carried away’ (HYD, eps.1). This event is the first step towards regaining her identity. Through this action she symbolically undermines the hierarchical structures of the school and society, an act that paves the way for her acceptance by F4 as a person of high moral standing and as a feminine peer.

In addition to creating a space for the powerless to negotiate access to social rights, Hana Yori Dango also demonstrates the strong moral fibre of the powerless who, for example, resist the approaches of a corrupt organisation attempting to buy its way out of a problematic situation. After getting information about Tsukushi’s family background, the matriarch of the powerful Dōmyōji family visits Tsukushi’s parents and offers them US $1million for Tsukushi to stay away from her son. The family turns down the offer with Tsukushi’s mother pouring salt over the visitor as a symbolic gesture of cleansing that situates the Dōmyōji matriarch (Proppian villain) as an outsider polluted by calculating ambition.20 Tsukushi’s mother, on the other hand, claims her pride and honour over money when she declares: You don’t understand the feeling of a mother whose child is being insulted? Do you think the poor cannot be a mother?’ (MG, eps.10).

All versions rely on creating a tension between the gender divisions of institutionalised male self-centredness against discursive feminine resistance. When Tsukasa issues an order to a group of his fellow male students to make life hell for Tsukushi, the male gang, hormones unleashed, corners the protagonist in a sexual attack. Although she puts up a fight, Tsukushi is outnumbered and physically overpowered. This violent scene is interrupted by the abrupt appearance of Rui (Proppian helper), who steps in and tells the attackers to get lost. While Tsukushi’s sense of helplessness has reduced her to tears, the event triggers her revolt against the forces that have attempted to violate her. The very next day she confronts Tsukasa and declares war’. In this way Tsukushi is portrayed not just as a target of oppression but also as someone invested with the vitality of a weed grass’ that has the ability to rebound against male coercion.

As the story progresses and Tsukushi and Tsukasa reconcile some of their differences, violence returns in another form precipitated by Jyunpei Oribe (Proppian dispatcher)21 and a group of students bearing a grudge for past bullying experiences condoned by Tsukasa. Tsukushi is kidnapped by this group in order to lure Tsukasa to a place where the group can extract their revenge on the F4 leader. In order to protect Tsukushi, Tsukasa declines to fight back. Instead, it is Tsukushi who, although tied to a chair, does her best to protect her friend by throwing her body between Tsukasa and his attackers and taking their blows with the chair. Having made their point and seeing Tsukushi’s devoted self-sacrifice the others give up and leave.

This scene represents a significant rupture in the dynamics of power and a breakdown of established structures leading to a reversal of gender roles which sees feminine power actualised and the establishment overthrown. To extend this analogy beyond the specifics of the capitalist de-odorised text and into the socio-historic context, we might see this event as a re-configuring of power relations across East Asia which situates masculine’ Japan as conceding cultural superiority to its former feminine’ colonial states. With this possibility in mind, it is to be expected, then, that the depiction of rupture in BOF and MG is more violent and extreme than in HYD, corresponding to the traumatic experience of colonisation and, at least in the case of Korea, loss of identity. The melodrama provides a style that can express the emotional truths of this historical reality’22 in spite of the fact that this is concealed behind a superficial façade of universal experience.

The Family

Although there are degrees of difference between versions, the family is represented as a coherent unit throughout the drama so that familial ties and sense of duty are featured in each episode in the series. In all versions, the father either struggles and gets laid off or loses the family business, a reflection of the economic climate of Asia in the early 2000s. Faced with economic crisis, the father loses more money through gambling, forcing the family to move to a provincial area. Subscribing to rather old-fashioned ethical values, Tsukushi works part time and helps support her family members who, despite their lower socio-economic status, each make sacrifices in order to send her to the prestigious school she attends. It is the hope of the family that there she will have the opportunity to meet a boy from a rich family and marry into wealth, thereby ensuring family financial security in the longer term.

In the Asian middle class context, studiousness and success in education cannot be underestimated. Children are expected to attain the highest possible standard of education and thus be better resourced to provide for their aging parents. Jeong-Kyu Lee articulates Asiatic values as centering on Confucian culture and higher education in the East Asia region’.23 Confucianism, as a socio-political construct, is based on a hierarchical authoritative order’ which then supports reciprocal humane relationships’. According to Lee, obedience to authority leads to homogeneously closed organisational systems’ while relationships that are based on reciprocity lead to paternalism or favoritism’.24 There are doubts that there is any natural’ Confucian ethic, nevertheless, it is clearly the case that, in defining an identity based on a Confucianist model as morally superior to a corrupt West, this ethic has taken hold of the public imaginary throughout East Asia.

Tsukushi does not like the idea of attending the prestigious school. She feels very uncomfortable and out of place’ in the environment of obedience to the hierarchal authoritative order. She confides to her best friend from the previous school, If not for my mother, I would not attend that school’ (MG, eps.1). With this statement Tsukushi reinforces the position of family first’ while also acknowledging her mother as more significant than her father. We might note that this dominance of the mother presents a significant rupture of the Confucian model outlined above. As the story progresses, Tsukasa’s mother uses trickery and influential power to pull her son and Tsukushi apart, a tactic which directly affects the financial position of the families of Tsukushi and her best friend. Anticipating the possible fragmentation of her family, Tsukushi gives up Tsukasa. He also lets her go in order to focus on the business affairs of his own family. An arranged engagement quickly follows for Tsukasa, so keeping the Dōmyōji empire as an homogenously closed organisational system’.

The father as a direct figure of authoritative significance is absent in all versions of Hana Yori Dango. Tomoko Hamada’s 1996 study25 foregrounds the loss of male authoritative power of businessmen in Japan. She argues that the salary man has come greatly to resemble the ideal nineteenth century Victorian middle-class woman-driven by duty and loyalty, subservient and other-directed’. Hamada goes on to conclude that in the post-postmodern megalopolis, Japanese men, women and children – whom I have characterized as the absent father, the feminized son, the selfish mother, and the disobedient daughter – face the task of establishing new and diverse meanings of the family and weaving multiple images of work and play’.

In MG, (eps.5), this demand for new and diverse’ meanings of family’ is evident when Shan Cai wonders if her father has been promoted. Her mother exclaims, How can it be your Papa? Your papa will never become a manager in this lifetime — even in our home, the title of ‘Manager’ is held by me!’. This shows that the father in the Taiwan version has no status either socially or domestically. The HYD father, too, has a subordinate role. For instance, he looks forward to receiving a small beer allowance from the mother who controls the family’s purse strings in order to pay for Tsukushi’s school fees.

Two important characters in the story that carry symbolic functions as substitute family members are Rui, one of the F4, and Tama, the head maid in the Dōmyōji household (another Proppian helper). Devoted to empathising with Tsukushi, Rui functions as a brother/helper while also playing the third man in the story’s love triangle. In difficult situations, Rui is there to back Tsukushi up and even to rescue her. For instance, Rui’s first appearance in the narrative comes when Tsukushi is bullied at Tsukasa’s orders and Rui wards off her attackers. This foregrounds the dynamics that operate for the rest of the drama between Tsukushi, Rui and Tsukasa.

Tama is an elderly and wise figure who functions as an advisor, a symbol of compassion, and a caretaker of traditional rules of conduct for the Dōmyōji family. Having been in charge of the day-to-day running of the household since the days of Tsukasa’s grandfather — the patriarch — it is she who sets standards for the other family members. In one scene, Tama angrily berates Tsukasa’s mother to be quiet’, suggesting that she (Tama) carries a responsibility bestowed by the grandfather for all household matters. In this sense, new’ matriarchal power is played against old patriarchal established customs.

The Makeover: Transformation and Desire

In all versions of Hana Yori Dango, the narrative embraces the transformation of Tsukushi in a fairytale progression from commoner to princess, a transformation aided by characters assigned with certain powers’ to effect her destiny. While a tough weed’ by nature who can fight her way through the mechanisms of suppression in the school, Tsukushi needs’ to be rescued and taken care of by others. Colette Dowling (1990) refers to the unconscious desire to be saved and carried away in the arms of a man as the Cinderella Complex’, which Dowling argues is evoked through women’s unconscious fear of becoming independent and alone. While this hypothesis has some application to Hana Yori Dango there are two additional points worth considering within the Asian context. Firstly, it may be that the fear of becoming independent from the family is an oxymoron in the case of the girl or young woman in Asia. Independence from the family is different to independence for the family, which has been suggested as Tsukushi’s motivation for attending the school. The second consideration concerns the male fear of women who seek to be independent and alone. For example, the fact that Tsukasa dresses up and transforms the wild and independent Tsukushi into someone he can tame and control suggests a male centred motive based on fear of the unknown woman who can operate independently of a man.

The problematic of the Cinderella complex as male centred fear of female independence versus female centred fear of becoming independent is apparent in the opening episode scene of Tsukushi’s first transformation following her being kidnapped and drugged by Tsukasa’s bodyguards and taken to Tsukasa’s mansion. Here, she is given a facial, hair treatment, a gorgeous black dress and jewellery before being taken into Tsukasa’s parlour where he tries to buy her undivided, and future, attention. Tsukushi is stunned by this forced transformation which feels alien to her. Unable to compromise her feelings of selfhood and independence, she demands her own clothes and runs off.

Although this set of actions appears not to support the Cinderella complex of being swept away by a man, the purpose of this scene, I suggest, is twofold. Firstly, kidnapping and transformation identifies the protagonist as fearful and anxious when facing a crisis of self identity. In other words, there is a conflict between her present sense of self and the possibility for a future new identity that suggests a desire for knowledge of a hidden, perhaps forbidden, self ‘.26 Secondly, the scene is used to create tension that is later released with Tsukushi’s acceptance and subsequent dependence on Tsukasa’s status and financial resources.

Susan Napier, in discussing Japanese shōjo anime, notes that, while the romantic comedy presents a world in which women are growing increasingly independent, at the same time, the fundamental gender division between the supportive woman and the libidinous male seems to remain miraculously intact’.27 Napier adds that the traditions of romance become comical when the woman is endowed with powers that destabilise the conventions of hierarchy, place and status. The tension created in the dynamic of idealised stability and fantastic chaos is an important source of creative energy sustaining the HYD narrative. The facts of a common girl being able to enter the elitist school, being labelled as unique and, managing to capture the heart of the male figurehead become the fantastic elements that combine to produce the fairytale. However, Tsukushi cannot win the heart of the prince’ on her own. Her transformation involves helpers, donors and rescuers as outlined using Propp’s archetypes for fairytales. The declaration of war’ scene and the first punch’ are the counter actions defining Tsukushi as the Proppian hero and represent the moment when the cruel prince’ is dethroned and his humanistic sensibilities awakened.

The roles of donor, rescuer and protector are tied to the desire of the protagonist to be transformed. In Asia, the Cinderella fairytale is often used in popular culture because women desire to be given a makeover’ and be transformed by an external agency to effect their emancipation from the perceived narrow confinement of their lives. The typical transformation found in girls’ comics, where the make-over is regarded as a marker of femininity, involves clothes and make-up.28 The desire to transform reflects the problematic of identity in the contemporary world and reveals deep-rooted fears and anxieties about relationships and the status of the body.29

Tsukushi as Heroine

In shōjo manga, the basic theme of the romantic’ genre over the past twenty five years has been affirmation of the young woman protagonist by another, typically a prince’ like character.30 Girls, generally speaking, know they are not special – not beautiful, not smart, not rich and not talented — so that the acceptance of such ordinariness by the prince’ is the core element appealing to a reading audience. Elise K. Tipton assesses the way comic-based representations of women characterise both the preservation and subversion of traditional female roles.31 Tsukushi upholds traditional values of passivity, self-sacrifice and virginity while also confronting and resisting corruption found within the school’s patriarchal establishment.

In some respects, Tsukushi is like the protagonist in the hit soap opera, Oshin, broadcast on Japanese television (NHK)32 as a morning serial between April, 1983 and March, 1984. Paul Harvey describes the heroine of Japanese morning soap opera (asadora) as a comic hero – comic in the sense that she is able, through her own effort, to transform a hostile environment. Harvey also points out that the heroine carries two burdens: that of revitaliser of her own family that has often been disrupted by ill- fortune, and that of seeker of a non-traditional’ dream in which female desire for self- improvement and social innovation comes up against established power structures.33 So, too, in Hana Yori Dango is Tsukushi occupied with the dual concerns of bad luck in the family and of self transformation that must confront and deal with obstacles such as social class difference, bullying and a villainous and uncompromising matriarch (and perhaps future mother in law?). The way the protagonist negotiates her way around these obstacles’ varies between the three versions of the text and will be discussed in the following section to determine the extent to which versional variations gesture towards a localised idealisation of (post)modernity.

Korea, Taiwan and Japan: Analysing Differences

CTS began broadcasting MG into Taiwanese households in 2001. The series became an instant success for viewers accustomed to and tired of viewing tedious and drawn-out traditional’ prime-time dramas with conventions of local flavour, historical anguish and moral exhortations’.34 Where older dramas set out to reinforce traditional values and established codes of behaviour, the appearance of the post-trendy drama brought a new ethos for the young in the guise of romance as a tool to explore the Self using idol role models with whom youth could identify. Compared to traditional Taiwanese prime time drama, the format was fast paced, sophisticated, urban and modern, and packaged with the latest popular music including original songs performed by F4. Nevertheless, local tastes, such as family relationships, respect for elders, generational conflicts and superstition, were also built into the narrative. Despite these localisation strategies, the flavour remained Japanese by retaining the Japanese character names and through using sets containing Japanese style interior items such as tatami floor mats,35 shōji windows,36 and futon bedding. In addition, a number of locations, such as Okinawa as an F4 holiday destination and a traditional style hot-spring ryokan (Japanese inn) built in Taipei by the Japanese Imperial Army during the occupation of Taiwan, added to this flavour. While locations such as these may inflame negative memories of Japan as cultural hegemon and neo-coloniser for some older Taiwanese, according to Iwabuchi, history bears no such scars for the younger generation.37 For them, this popular culture idealisation of modernity is essentially non-political and fails to differentiate source from content. On the other hand, the Korean version has no trace of Japanese flavour – any association with the origins of BOF has been removed. Furthermore, a comparison of the various versions of Hana Yori Dango needs to address the use of character names and whether or not naming reflects any postcolonial bond between either Korea or Taiwan and Japan.

Naming and Depiction of the Heroine

MG kept the original Japanese name character read with Chinese pronunciation: exotic names that obviously indicate Japanese roots. One exception was Shan Cai (Japanese phonetic sound sugina), the characters for which indicate the mature Horsetail (Equisetum), a tough, green, poisonous plant. The name, Tsukushi’, invests Japanese audiences with a feeling of affinity with her character, which, associated with the image of this rural plant, further emphasises her commonality. Hence, although they are the same plant, shan cai (sugina)’ and tsukushi evoke very different images and impressions. The transformation from the soft to the tough plant provides a metaphor for the Taiwanese experience of colonisation, indicated as growth or departure from past (colonial) experiences toward a more independent position built around self-reliance. Both Shan Cai and Tsukushi are unusual names for girls, whereas Jan Di (grass), the name of the BOF protagonist, is not uncommon for girls in Korea. Grass’ Jan Di seems to be weaker than rural weed’ Shan Cai and Tsukushi. These observations reflect the suggestion put forward by Okyopyo Moon38 and cited by Harvey39 that Korean women have internalised the Confucian values that subordinate women to men to a greater degree than have Japanese women who, on the whole, exist in a more liberal society.

Furthermore, all other original character names in BOF have also been replaced with common Korean names. NEWSEN reports (11 Sep. 2009)40 that at a BOF press conference a representative of the Korean publisher announced that the company would not use the original Japanese names from HYD in spite of the fact that this was a condition of the production rights contract. The announcement nonetheless indicated that the Korean names would reflect the original character’s implied personality. However, apart from the obvious weed/grass’ analogy, it is hard to connect the Korean names with the Japanese original names,41 which could be interpreted as an intentional removal of any past associations with Japan as coloniser. Ascribing new names for each character can be additionally seen as a Korean effort to create a legacy and style different from the Japanese origin.

The Heroine as a mother

In HYD and MG, Tsukushi and Shan Cai represent a mother figure or the side of femininity for which Tsukasa and Dao Ming Si (the Tsukasa character), whose own mothers are distant and unknowable, really yearn. That is, their relationship with Tsukushi/Shan Cai is based on their (unsatisfied) need to know their mother. There is a scene from HYD which depicts Tsukushi and Tsukasa trapped in an elevator overnight and which shows the signified bond between the couple. The physical placement of the pair is representative on the one hand of twins in the womb, but also can be read as Tsukushi letting herself be a substitute mother for Tsukasa. The scene occurs after Tsukushi has repeatedly rejected Tsukasa’s overtures.

The womb image, however, is absent from BOF in which the pair are left at the top of a cable-car station and spend a cold night together sitting upright on a seat. The closeness and intimacy of HYD might be interpreted as a superior cultural intimacy (more modern, more Western, more colonial’, more Other) with closeness’ as a signifier for (post)modernity. In MG, the elevator is the set with Dao Ming Si lying with his head cradled in the lap of the sitting Shan Cai. The depiction of the cable-car scene in BOF represents a different interpretation of the protagonist, Jan Di, who carries less sense of a mother figure. For Jun Pyo, Jan Di symbolises the battle he must go through in order to release himself from the hegemony inscribed by his corporate family. Rather than Jan Di herself, it is Jan Di’s family that plays an important part in comforting and educating Jun Pyo in matters of interpersonal relations.

Confucian values and Family centredness

In an audience study of Korean drama, Lin and Tong emphasise the importance of the reflexivity of the audience in the portrayal of different kinds of family and traditional values often interpreted as Confucianist’. At the heart of these Korean dramas is what Lin and Tong’s informants describe as the Asian worldview’.42

The K-drama invests the family with a more central role. An example, unique to BOF, follows the salt throwing scene in Jan Di’s house. Jan Di’s mother then visits the mother of Jun Pyo (Tsukasa’s character) to respectfully ask forgiveness and, also, to borrow the money that she initially refused to accept. Salt is again used in the BOF story to express self-effacement when Jan Di’s desperate mother swallows her pride and begs for help from Madam Kang (the BOF matriarch). Despite Jan Di’s mother’s prostration, Madam Kang does not give ground easily. Instead, reflecting the hierarchical Confucian society, she coolly observes that everything has its systematic order: Wrongs must be apologized for, debts repaid, then help given. I am a businesswoman, so I cannot abide calculations and procedures that are not conducted properly’ (BOF, eps.12). Jan Di’s mother then takes out a parcel — a bowl of salt – which she pours over her own head in front of Madam Kang to plead for forgiveness. In this way, Jan Di’s mother humbles herself in order to save the family financially so that the family will be freed from losing their business and therefore able to stay together. In other words, even if it leads to a loss of face, the collective unity of family is seen as more important than the individual needs of family members.

Realism and Melodramatic differences

The sense of realism relates to the extent that the drama is both able to parallel and also be faithful to the sentiments of the shōjo narrative. Where HYD (and to a lesser degree, MG) invests the protagonist with power of her own agency, the Korean melodramatic spectacle of suffering results in an indigenised text mismatched with the Japanese shōjo narrative. The lack of realism in BOF is in some respects unfair, since the melodrama in this version evokes both the realism of a vicious colonial past and compressed modernisation under the surveillance of a repressive political system in Korea. Melodrama provides a style that is able to express the emotional truths of this historical reality.43 Furthermore, when hinged to the instability of colonial oppression, the genre can provide a framework that attests to the excess of violence depicted in BOF. Although the visual style of all versions is sustained through fantasy and romantic comedy, the safety of that fantasy is unexpectedly ruptured by the stark and brutal school violence depicted. This violence is emphasised to the greatest degree in BOF when compared to the other two versions.

In BOF and to a lesser extent MG, the melodrama is further enhanced through the stylised technique of incorporating flashback scenes into the narrative, whereby sentimentality is reinforced through replaying previous scenes. This technique of recapitulation serves several purposes. Firstly it is a cost-effective production technique that lengthens the series; secondly it reinforces previously viewed scenes; and, thirdly, it assists viewers to recollect the past and to recover, artefacts that effectively compress forms of historical experience’.44 Chow suggests the nostalgic response in recovering the memory of what has been lost results in a mosaic that produces not history but fantasies of time’.45 Flashbacks to a previous scene or to a past period in a character’s life sustain a sense of nostalgia that can also evoke a sense of pity in an audience. For example, in BOF Jun Pyo and Jan Di are walking through a dark park. Suddenly the park is lit with decorative lights pre-set by Jyn Pyo who asks his companion, Do you like it?’ Jan Di nods happily, It’s pretty. It’s like Christmas’. When Jun Pyo asks what’s so great about Christmas, she responds that it’s a happy day. Jun Pyo, however, disagrees. I’ve never had a happy memory of it’, he tells her. A flashback shows the audience a lonely little Jun Pyo being entertained by maids and his butler who also deliver impersonal gifts from his parents. This scene demonstrates the fantasies of time’ where the present is imagined as a pastiche and the past is represented through artefacts of historical experience. For Jan Di, who associates the event with happiness, the nostalgic response is positive, whereas for Jun Pyo, the response evokes memories of loneliness. I suggest that in this scene Christmas’ represents the period of (de)-colonisation in Korea with Jun Pyo representative of the cultural legacy of trauma for the Korean people, a legacy that Robert Hemmings argues operates from the same liminal space between memory and forgetting, rooted usually in the experience of surviving war’.46 In the analogy, Jan Di maintains the historical continuity of celebrating decolonisation and the opportunity to move forward’, whereas Jun Pyo continues to suffer from the twin effects of historical colonisation and an inability to reconciliate the past with the modern present.

Concluding Remarks

This article has investigated how modernity fashions the lifestyle and choices of East Asian youth represented through the fictional accounts narrated in Hana Yori Dango in order to problematise the extent to which the portrayal and decoding of (post) modern lifestyles across national boundaries allows for a plurality of culturally specific experiences. The ready acceptance of Hana Yori Dango as a text and aesthetic model across East Asia – despite quite different political structures and colonial experiences over the last century in the three sites discussed – points to the story’s resonance with common concerns, dreams and experiences. As templates for modernity, the three regional texts of Hana Yori Dango when presented at the localised site of decoding carry particular indigenised imprints that are seen to have several functions.

Firstly, the text itself must have universal appeal, the template of the Cinderella story can be superimposed upon the Asian imaginary to create culturally specific contexts. The encoder, informed through the production process, acts as a mediator of consciously constructed messages that serve to confirm and reinforce the audiences’ positive image of themselves. Furthermore, the post-trendy drama boom of the 1990s, which was advanced by production houses responding to the expectations of viewers, sought to reflect changes in contemporary society, particularly in the lives of women.

Secondly, the text has to be easily transposed onto a format for commodification and dispersal across cultural boundaries through the process of translation’ whereby moving idealised (Western) images of modernity into a new cultural space creates the potential for active engagement, reflexivity and adaptation. This process provides for a plurality of Asian national cultural responses not reducible to ideas generated from Western modernity. Post-colonial theory and post-structuralism frames the narrative as incomplete’, open’ and adaptable’ to a plurality of voices’, supporting the view that Hana Yori Dango allows for a multiplicity of culturally specific translations.

Thirdly, the text has to provide for the needs’ of the audience: the post- trendy drama offers a tool for envisioning the desire to create a positive self image as a global subject’ rather than for a local colonised subject’. The contemporary foreign urban landscape provides the audience with an index of realism, envisioned through an imaginary of modernity’ that provides for a different but equal’ East Asian contemporaneity. Moreover, through choices tailor made by the television industry in order to predict and secure popularity, the illusion of direct access to specific models of postmodern lifestyles is maintained through active decoding by the viewer. In this scenario there will be a relationship between the popularity of a programme and the extent to which it reinforces the ideological position of the majority audience – a position that caters for an Asian worldview’ based on varying degrees of Confucian ideals.

Fourthly, postmodernity as a heteroglossic phenomenon, is received, processed and understood’ non-uniformly through indigenised texts at local sites of reception – thereby allowing for an appreciation of difference and for a multiplicity of effects. Hana Yori Dango succeeds in celebrating the representation of a contrived and illusory reality’.

This article has examined the circulation and reception of the original shÅjo manga text, Hana Yori Dango, through the three sites of Taiwan, Korea and Japan to both identify similarities and to investigate also specific differences between versions and how these differences relate to both cultural distancing and to cultural proximity. The distance-closeness binary is most informed by the historical relationship Japan has had under Western socio-politico-cultural subjugation that in turn has informed the colonial relationship both Taiwan and Korea have had with Japan. The remnant of these (ongoing) relationships has directed a subjective encoding onto MG, HYD and BOF. Therefore, the appearance of similarity between versions is underscored by social, political and cultural differences contextualised locally and, promoted globally as a polymorphous and multilayered plurality.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- J. A. A. Stockwin uses the term in ”Series Editor’s Preface“ in Globalizing Japan. ↩

- Iwabuchi, Feeling Asian Modernities, p. 165. ↩

- Iwabuchi, Recentering Globalization, p. 203. ↩

- The comic has been remade into not only three official dramas (in Taiwan 2001, Japan 2005 & 2007, and Korea 2009) but also one spin-off (in Taiwan 2001), two live action movies (in Japan 1995 and 2000), one anime movie (in Japan 1997) as well as an anime series (in Japan 1996). Hana Yori Dango has sold over 54 million copies and has been the best-selling shōjo manga in Japan, http://www.toei-anime.co.jp/tv/hanadan/ ↩

- Margaret (Māgaretto) is a popular biweekly Japanese shōjo manga magazine for young girls published by Shueisha since Margaret Official Site, http://margaret.shueisha.co.jp/ ↩

- The title, Hana Yori Dango, is a play on words on a Japanese saying, Dumplings before Flowers'(Hana Yori Dango‘) literally, dango (rice dumplings/ pudding) rather than flowers’. Dumplings before flowers’ is a well-known Japanese expression referring to people who attend Hanami (cherry blossom viewing parties). These people prefer food and drink to the abstract appreciation of the flowers’ The expression has thereby come to refer to a preference for practical things rather than aesthetics/praise (GENIUS Japanese-English Dictionary Second Edition, Konishi and Minamide, 2003). The author of Hana Yori Dango created a play on words by changing the characters of the title to mean Boys over Flowers’, rather than dumplings over flowers.’ Note that boys’ is normally read danshi, but the Japanese phonetic guide hiragana indicates that it reads dango. ↩

- Ching, Becoming Japanese’: Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation. ↩

- Tokyo Broadcasting System Television. ↩

- Official Site, http://www.tbs.co.jp/hanayoridango/. ↩

- KBS2TV is one of the terrestrial television channels of the Korean Broadcasting System, which broadcasts mainly lifestyle and entertainment programs and dramas. KBS Official Site, http://www.kbs.co.kr/. ↩

- Official Site, http://www.tnsmk.co.kr/. ↩

- Robertson, Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular Culture in Modern Japan. ↩

- Le, Possibility and Revelation in Card Captor Sakura Through the Subversion of Normative Sex, Gender, and Social Expectation, p. 90. ↩

- Fujimoto, Onna to Ren’ai: Shōjo Manga no Rabu Iryūjyon’. ↩

- Tsukushi means spores of Equisetum’ (commonly known as Horsetail). Horsetail is native to moist forests, forest edges, stream banks, swamps and fens throughout North America and The stalks arise from rhizomes that are deep underground and almost impossible to dig out. The foliage is poisonous to grazing animals, whereas, the young fertile stems bearing strobilus are cooked and eaten by humans in Japan, although considerable preparation is required and care should be taken (Ashkenazi and Jacob, p. 232). ↩

- Vladimir Propp (1895 -1970) was a Russian formalist scholar who analysed the basic plot components of around 100 Russian folk tales to identify their simplest irreducible narrative elements (narratemes). After the initial situation is depicted, the tale follows a sequence of 31 functions, not necessarily in strict order. ↩

- Fiske, Television Culture, p. 137. ↩

- Casey et al., Television Studies, p. 55. ↩

- Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, p. 106. ↩

- In the native Japanese religion, Shinto, salt is used for ritual purification of locations and people, for instance in sumo wrestling. Salt has a long history of use in rituals of purification, magical protection, and blessing in various parts of the world (Latham, 1982). ↩

- Jyunpei Oribe plays an important role as a Proppian dispatcher, who, by initiating this event, makes Tsukushi realise her true feeling toward Tsukasa. ↩

- McHugh and Abelmann, South Korean Golden Age Melodrama, pp. 5-7. ↩

- Lee, Asiatic values in East Asian higher Education’, p. 45. ↩

- Ibid., p. 48 ↩

- Hamada, Absent Fathers, Feminized Sons, Selfish Mothers and Disobedient Daughters’. ↩

- Norris, Cyborg girls and shape-shifters: The discovery of difference by Anime and Manga Fans in Australia’. ↩

- Napier, Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle, p. 197. ↩

- Saitō, Kōitten Ron, p. 27. ↩

- Napier, op. cit., pp. 291-292. ↩

- Hashimoto, Hana saku Otometachi no Kinpira Gobō Kōhen, pp. 97-130. ↩

- Tipton, Being women in Japan 1970 — 2000′, p. 224. ↩

- Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai: Japan Broadcasting Corporation. ↩

- Harvey, Nonchan’s Dream: NHK Morning Serialised Television Novels’, pp. 137-140. ↩

- Liu and Chen, Cloning, adaptation, import and originality: Taiwan in the global television format business’, p. 68. ↩

- A tatami floor mat is a traditional type of Japanese flooring, which is made of rice straw to form the core with a covering of woven soft rushes (Sugiura and Gillespie, 1993, p. 146). ↩

- A shōji is a door, window or room divider consisting of translucent traditional paper (washi) over a frame of wood which holds together a sort of grid of wood or bamboo (Sugiura and Gillespie, 1993, p. 158). ↩

- Iwabuchi, Recentering Globalization, p. 125. ↩

- Moon, Confucianism and gender segregation in Japan and Korea’. ↩

- Harvey, op. cit., p. 134. ↩

- http://www.newsen.com/news_view.phpuid=200909111230401020 (Korean). ↩

- All the Korean character names are written in Hangul (Korean phonetic writing system). Since Hangul is unable to carry implicit meaning(s), I have referred to the meaning of each character’s Korean name released in the BOF official site (Chinese version): http://www.ctv.com.tw/event1/meteor_garden/. Jan Di (Grass/weed). Jun Pyo (Emergence/representation of excellence/brightness), the name expresses Jun Pyo’s position in his family as a successor of a big Ji Hoo (Heartfelt wisdom) characterised as a gentle boy able to look after and support Jan Di. ↩

- Lin and Tong, Re-Imagining a Cosmopolitan Asian Us’: Korean Media Flows and Imaginaries of Asian Modern Femininities’, p. 99. ↩

- McHugh and Abelmann, op. cit., pp. 5-7. ↩

- Chow, A Souvenir of Love’, p. 211. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Hemmings, Modern Nostalgia, p. 3. ↩